Howard Rhodes: Civic Nationalism and Intervention in Libya

When President Obama spoke last night about the military intervention in Libya, he confronted a public both stunned and skeptical.

The military action was the product of a complex set of political considerations undertaken at great speed. The rapidity of the political run-up to the initial attack rendered ordinary processes of democratic consultation confused and confusing. Despite the fact that the attack on Libya was legally authorized by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, thus sanctioning the action with the highest form of justification purportedly representing international consensus, many people in America and abroad continue to find the moral and political justifications for the act unclear or unconvincing. Many citizens are skeptical, in particular, about the extent to which protecting civilians represents the actual motive for the undertaking. While the president’s speech forcefully defended the humanitarian grounds for the Libya intervention, it also suggested other, arguably more powerful motivations for using force against the Gaddafi regime. Attacking Libya, the president suggests, is not simply an act of liberal humanitarianism, but of fidelity to America’s revolutionary origins.

President Obama’s principal justification for attacking the Gaddafi regime was to prevent a massacre in the city of Benghazi. Against the background of a history of foot-dragging and inaction by previous American regimes in the face of humanitarian crises, President Obama and his advisors determined that it would be better to use force early rather than “wait for images of mass graves” to flood television screens around the world.

This decision carries enormous risks. It justifies the use of force by reference to a plausible, but still hypothetical scenario in which the Gaddafi regime slaughters civilians by the thousands. It takes literally the hyperbolic threats of a dictator for whom hyperbole is a basic modus operandi and uses those words as proof positive of atrocious intent.

The president’s judgment may in fact have been correct. Perhaps Gaddafi’s treatment of the rebellious population would have involved massacre, mass graves, systematic rape, and other horrors of mass atrocity. But we will never know, and while it is better never to know such things, this not-knowing leaves the president—and the American people—with a situation in which the principal justification for using force is underdetermined.

A great deal of the president’s speech hinges on the extent to which his audience accepts his claim that civil war in Libya would involve “violence on a horrific scale.” The president does not clearly succeed in distinguishing the violence in Libya from the violence in other countries such as Yemen and Syria. This makes him vulnerable to claims that his administration is being inconsistent by attacking Libya but ignoring other situations. President Obama essentially sidesteps the issue by simply acknowledging that America cannot use force everywhere while asserting that this cannot be a reason for inaction in the present case. It is true that intervention in one case does not commit one to a perverse ethic of consistency demanding intervention in every case. But if Libya is not clearly distinguished by extraordinary violence, then the president’s claim that protecting civilians is the primary purpose of intervening in Libya is very weak indeed.

Perhaps, however, the protection of civilians is only one reason for using force in Libya, one that is most acceptable legally and internationally but which is essentially on a par with other reasons for action in this case. The president mentioned the desire both to send a signal to other authoritarian regimes in the region that their violence will not go unanswered and to assist the self-determination of the Libyan people. This is where President Obama’s remarks about American political identity and revolutionary origins are relevant. According to the president, passivity in the face of the Libyan rebellion would have been a “betrayal of who we are” as a nation. America is a nation born of a revolution. Our revolutionary origins have left an indelible mark on our national mythos, our sense of ourselves in our grander moments. It inclines the American people toward sympathy with others who take up arms to fight for freedom and, in some cases, commits us to coming to their aid, through force of arms if necessary. For us, defending human dignity sometimes involves using force to support a rebellion. Or so suggests the president. If one accepts this as a plausible account of how Americans justify the use of force—an account focused more on notions of national identity and revolutionary values than on human rights or humanitarian protection—then one is presented with an account more in keeping with America’s ongoing efforts to shape the global environment according to its revolutionary values.

If America’s identity as a revolutionary regime is crucial to how the president justified the use of force in Libya, then the intervention could amount to a dangerous and destabilizing act of “exporting the revolution.” But America, according to the president, is not only an “advocate of human freedom.” It has also acquired a hard-earned identity as an “anchor of global security.” American revolutionary values, on this account, cannot be understood independently of the concern to preserve global order by supporting international institutions, securing cooperation and consensus, and observing the realistic limits of military force. From this point of view, what distinguishes Libya from other situations is not the severity of its violence, but the fact that the opposition to Gaddafi seems actually to have organized itself into a genuine rebellion. At the beginning of the debate over Libya at least, the Libyan rebels seem to have organized themselves sufficiently to promise both an effective armed resistance and a potential provisional government in the wake of Gaddafi’s demise. This perception of rebel organization seemed to answer the concern that any intervention not result in broader political destabilization. We know now that the Libyan rebels are poorly organized, untutored in the art of government, and largely unknown. Time will tell, then, whether the American administration’s support of Libya’s rebellion will cause harms disproportionate to the goods achieved.

Whatever the future brings, one cannot understand adequately the intervention in Libya without coming to terms with the dance between nationalism, liberal internationalism, and political realism in the president’s speech. When the claims about international consensus and humanitarian concern break down under critical scrutiny, only the claims about national values remain. These national values, and the national identity they presuppose, need not and should not be understood independently of humanitarian concern. Without vital notions of national identity and accompanying notions of honor and fidelity, however, humanitarian aspirations lack ways of actually motivating action.

None of this, of course, answers the question of whether the intervention in Libya was just. But any moral judgment depends upon first acquiring an adequate description of the act under question.

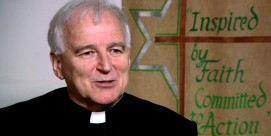

Howard Rhodes teaches at the University of Iowa College of Law.