JUDY VALENTE: Sunrise at the Abbey of Gethsemani in the misty hills south of Louisville, Kentucky. The 55 Trappist monks who live here awake at 3 a.m. to begin their daily regimen of prayer and work—in silence. They gather for communal prayer several times a day. They will rarely venture outside the walls. For most, their lives will end here.

The monks support the abbey by making fruitcakes and other products which are sold to the public. Much of the monastery’s 2,300 acres is leased to local farmers.

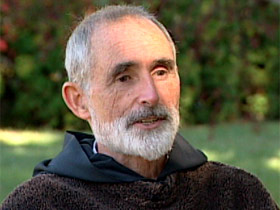

Brother PAUL QUENON (Abbey of Gethsemani): The essence of the Trappist life would be living in God. And I don’t think I would want to say much more than that. And of course, you’re living in God with other people in the same community. And it’s a life of continual prayer. And it’s a life of deepening—going deeper into your own capacity to love and to live with God.

VALENTE: In 1941 Merton, then an aspiring young writer—and a recent convert to Catholicism—arrived here seeking to radically change his life. Merton was to have a striking message.

MORGAN ATKINSON (Documentary Producer): He said that anybody could have a deeply spiritual life it they care to. Any person on the street, if they were committed to it and devoted to trying it, then that path was open to them.

VALENTE: For Merton, the “deeply spiritual life” meant the “experience” of God’s presence and love at all times, combining that with action in everyday life.

Paul Pearson oversees the Merton Center at Bellarmine University in Louisville.

Dr. PAUL PEARSON (Director and Archivist, The Thomas Merton Center, Bellarmine University): The essence of Merton’s spirituality is, I think the humanity of it, that he really speaks to ordinary people. He knows so well the great classics of Christian spirituality, but he can interpret them in a way that people in our world today can understand and can relate to.

VALENTE: He spoke especially to lay Catholics in what was then a firmly hierarchical church.

Dr. PEARSON: Spirituality really belonged to the monks and nuns and bishops and what have you. Whereas, you know, your ordinary lay person went to Mass on Sundays. The mass was in Latin. They said the rosary and that was the extent of it. And Merton, I think, really opened up that whole realm of contemplation and spirituality for people.

VALENTE: Merton’s parents had died when he was young. By his own account, he lived a rootless, hedonistic life. It was rumored he had fathered a child out of wedlock while a student at the University of Cambridge. At New York’s Columbia University, he continued to feel morally adrift, emotionally bereft. As a world-weary 26-year-old, Merton wrote these words, read by Morgan Atkinson.

Mr. ATKINSON (reading from Merton’s journal): Finally has come the time to go the Trappists and try to get in. And be completely quiet in front of the face of peace. It is time to stop being sick and really get well. Out here I could think and yet I could not get to any conclusions. But there was one thought running around and around in my mind: to be a monk—to be a monk!

VALENTE: Thomas Merton not only became a monk. He would become a best-selling author and one of the most influential spiritual thinkers of his time. A fellow writer called him “an investigative reporter going into the inner workings of the soul.”

As a novice at Gethsemani, Brother Paul Quenon received spiritual direction from Merton, known as Father Louis.

Brother QUENON: He doesn’t think of the whole world as, you know, monks. But on the other hand, he can talk to the monk in each person. He sees it as a deep enough thing that somehow everybody has the capacity to come to the same kind of intensity and depth of experience of God.

Dr. PEARSON: Now this exhibit is all of Merton’s published work with their varying editions and foreign translations. Merton’s now been translated into, I think it’s 30 languages.

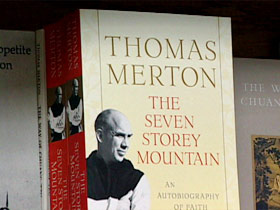

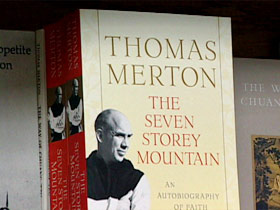

VALENTE: In 1948, when he was 33 years old, Merton published his autobiography, “The Seven Storey Mountain,” taking his title from a scene in Dante’s “Purgatory.” The book became an overnight bestseller. Sister Suzanne Zuercher is a Benedictine nun who has written extensively about Merton.

Sister SUZANNE ZUERCHER (O.S.B): I knew that I needed to be in monastic life. I knew he was someone who spoke to me as no one had ever spoken to me. He’s funny, he’s profound, he’s human, he’s down to earth, he’s practical, he’s concrete.

MIKE BRENNAN (Baggage Handler, American Airlines): This is the one book we just finished reading …

VALENTE: Mike Brennan is a baggage handler for American Airlines in Chicago. His home is full of Merton books and memorabilia.

Mr. BRENNAN: Working at O’Hare Airport—noisy, crazy, constant activity, constant stimulation—it’s really nice to find a way to let go of all that stimulus and activity and think of being connected with the Lord. And I learned that from Merton.

VALENTE: Merton’s fame allowed him to correspond with presidents, popes and Nobel Prize winners. But as his public reputation grew, he retreated further into solitude and silence. He would spend a few hours a day in this small wooden shed, writing and meditating. But it wasn’t enough.

Brother QUENON: He wanted to have more time for writing, for meditation.

VALENTE: He would later get permission from his abbot to live—as a hermit—in this tiny cottage about a half mile from the monastery.

Brother QUENON: He loved being in the midst of nature, you know. The birds were his friends.

VALENTE: What do you think he did out here?

Brother QUENON: Well, read a lot and wrote. For him, praying was just to abide in the presence—the presence of the Lord.

(touring cottage): There’s the kitchen and then a bedroom. And then, a chapel was added later on.

VALENTE: Merton wrote this in his journal:

Mr. ATKINSON (reading from Merton’s journal): For myself I have only one desire and that is the desire for solitude: to disappear into God; to be submerged in His peace; to be lost in the secret of His space. I have gone to the hermitage not because I hate the world. I go to the hermitage to deepen my consciousness, to be more in communion with the world.

VALENTE: His output was enormous. Over a 20-year period he would write 60 books on topics ranging from contemplative prayer to non-violence. He also wrote poetry, essays and criticism.

In the 1960s, Merton became increasingly controversial. He began writing on issues of the day, like civil rights, materialism and the nuclear arms race. His superiors blocked the publication of some of his most strident anti-war writings.

Dr. PEARSON: As he changed from the world-denying monk to the world embracing monk of the ‘60s, you know, people began to think, “Why should he be writing on these issues. He’s away in a monastery. What does he know about them?’”

VALENTE: In 1966, Merton spent several weeks in a Louisville hospital, recovering from back surgery. There he met and fell in love with a young student nurse. He was 51 years old at the time.

Sister ZUERCHER: It was very brief. It was very intense. It was very passionate. He sometimes felt he had abandoned his vows. And at other times, he felt he was living the vows of growth and fulfillment.

VALENTE: The two would sometimes meet clandestinely in secluded parts of the monastery grounds. Within a matter of months, the relationship was over. But Merton had been changed.

Sr. SUZANNE: From that time on, he never again thought of himself as being unloved or unlovable. And he himself learned to love in this relationship and that was the part of himself that he always felt had been under-developed.

VALENTE: Merton re-dedicated himself to his monastic life. He became increasingly interested in Buddhism and Asian monasticism. In 1968, he received permission to attend a conference on monasticism in Bangkok. There is rare footage of Merton from that conference.

THOMAS MERTON (in video from 1968 conference): That’s a thing of the past now, to be suspicious of other religions, and to look always at what is weakest in other religions and what is highest in our own religion. This double standard in dealing with religions—this has to stop.

VALENTE: Hours after this film was made, Merton was dead—electrocuted after touching a fan with faulty wiring in his hotel room. He was 53.

His reputation has only grown since his death. Working with manuscripts he left behind, scholars have published 60 more of his books, including seven volumes of his personal journals. But, as a monk, Merton left behind few personal possessions: his work shirt; a cup; boots; eyeglasses.

Dr. PEARSON: With the death of Thomas Merton, we lost really one of the great Catholic voices, one of the great prophetic figures within the Catholic Church. And I think that’s why his books are still selling, why they’re still being translated because that message is as relevant today as when he wrote it.

VALENTE: Toward the end of his life Merton wrote, “Our real journey is interior.” For those seeking to take that journey, he remains an essential guide.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Judy Valente at the Abbey of Gethsemani.

ABERNETHY: An hour-long documentary, “Soul Searching: The Journey of Thomas Merton,” will be shown on many PBS stations next month.