In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Papal Selection

After Pope Benedict XVI’s announcement that he is resigning February 28, 2013, the Roman Catholic Church is preparing for a conclave, where cardinals under the age of 80 will gather to elect his successor. Managing editor Kim Lawton looked at the centuries-old process of selecting the pope.

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus says his disciple Peter is the rock upon which the church will be built. He tells Peter, “I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven.” The Roman Catholic Church teaches that its leader, the pope, is part of an unbroken succession from Peter. Selecting Peter’s successor is a momentous occasion.

JOHN L. ALLEN, JR. (National Catholic Reporter): What you have in a conclave is you have a moment of change on a world scale that the change in no other office, the change of no other leader, comes close to replicating. The transition in American presidents does not have the gravity, does not have the global significance that a change in the papacy does.

LAWTON: The details of the process have evolved greatly over the centuries. Under current rules, after the death or resignation of a pope, cardinals under the age of 80 have between 15 and 20 days to gather in Rome for the conclave. Until a new pope is elected, the College of Cardinals governs the church, but with limited powers.

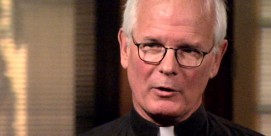

REV. THOMAS REESE, S.J. (Woodstock Theological Center, Georgetown Univ.): When the cardinals meet to elect a pope, first of all they’re locked up so that they cannot be influenced by anything from the outside, and also so they can maintain secrecy. There will be no cell phones, no radios, no newspapers, no telephones, no communication with the outside world.

LAWTON: Every day, the cardinals assemble in the nearby Sistine Chapel, under the watchful eyes of Michelangelo’s restored frescoes. One of the first orders of business is swearing an oath of absolute secrecy. Under modern church rules, the conclave area is swept for bugs and other surveillance devices.

ALLEN: The cardinals are not supposed to be casting votes based on their image or based on political considerations, but based on who they really think is best for the church. And the notion is that doing that behind closed doors makes that somehow easier, makes that more possible.

LAWTON: Sequestered inside the Sistine Chapel, the cardinals vote by paper ballot, guided, the church says, by the Holy Spirit.

REESE: They have a small piece of paper, and on it they write the name of the person that they are voting for. Then they fold that piece of paper in two and hold it in their hand and march up one by one, holding it in the air so that everyone can see that there’s only one ballot here.

LAWTON: Selected “cardinal-scrutineers” count the number of ballots, making sure they correspond with the number of cardinals in the room. They then tally the ballots aloud. The pope is chosen by a two-thirds vote. There can be four votes a day. After three days, the voting can be suspended for a day of further prayer and discussion. Technically, any baptized male can be elected pope, although since the fourteenth century he has come from the College of Cardinals. After each round of voting, the ballots are burned in a special stove that has been used since the beginning of the twentieth century.

REESE: If the ballot had not elected a pope, they would put chemicals in to make the smoke black. If a pope is elected, they put certain chemicals into the stove with the ballots, so that the smoke comes out white.

LAWTON: Outside, people gather in St. Peter’s Square to pray and to await the word from the conclave. Modern popes have made their own changes that could have a huge impact on the future. In 1975, Paul VI instituted the age limit of 80 and expanded the number of voting cardinals. John Paul II and Benedict XVI further expanded and internationalized the college of cardinals.

ALLEN: The odds of a pope who is not European and not Italian are much more than they ever have been, simply because numerically the blocs from those non-European places are much larger and therefore have the political capacity to put forward their candidates.

LAWTON: Another factor for the conclave is the proliferation of the media, which challenges the vow of secrecy, and perhaps also shapes the choices.

REESE: It’s going to have to be someone who is at ease being the center of attention with the media. That’s just part of the reality of being pope today, whether the church likes it or not.

LAWTON: Inevitably, observers are making up their short lists of candidates, lists that have already been revised many times. And beyond the politics and the process and the pageantry, for the world’s Catholics the conclave is ultimately a holy endeavor.

I’m Kim Lawton reporting.