In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

The Legacy of Howard Thurman: Mystic and Theologian

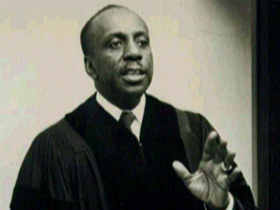

KIM LAWTON: On the campus of Morehouse College in Atlanta, a statue of Martin Luther King, Jr. Nearby, a monument to another, lesser-known Morehouse graduate, theologian and mystic Howard Thurman. Thurman had a profound spiritual impact on King and on many other civil rights leaders. Yet for much of the last half century, Thurman’s contributions have often been overlooked.

Dr. WALTER L. FLUKER (Director, Howard Thurman Papers Project, Morehouse College): Leaders like King do not arise out of a historical vacuum. There are movements and there are personalities who actually sow the seeds. Thurman is one of those persons who sows the seed. In fact, I don’t believe you’d get a Martin Luther King, Jr. without a Howard Thurman.

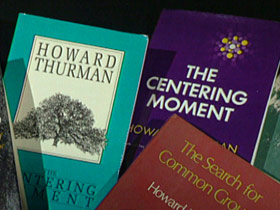

LAWTON: Thurman wrote 21 books and hundreds of sermons and articles about the connection between spiritual renewal and social change; about the unity of all creation, the building of community and the search for common ground. Now, more than 20 years after his death in 1981, Howard Thurman is finding a new audience.

Dr. ROBERT FRANKLIN (President, Interdenominational Theological Center): I think there is greater resonance today for many of the things in this thought, which only goes to show us that Dr. Thurman was way out ahead of his generation and he is, in fact, was a 21st century theologian working in the middle of the 20th century.

LAWTON: Howard Thurman was born at the turn of the last century in segregated Daytona, Florida. He was raised by his grandmother, a former slave.

Despite racial and economic obstacles, Thurman graduated from Morehouse and then Colgate-Rochester Divinity School in New York State. In 1932, he was appointed dean of the chapel at Howard University in Washington.

In 1935, Thurman led an African-American delegation to South Asia. In India, he and his wife met Mahatma Gandhi. They talked about oppression and freedom and nonviolence. Gandhi asked them to sing a spiritual, “Were you there when they crucified my Lord?”

Thurman returned to the United States and began reflecting about how the life and teachings of Jesus specifically applied to those facing suffering and oppression. In 1949, he synthesized that thinking in one of his best-known books, JESUS AND THE DISINHERITED.

Dr. FLUKER: The message of the book is basically in the form of a question: “What does the message of Jesus have to say to those whose backs are against the wall?”

LAWTON: That was his big theme — the backs against the wall. It came up again and again.

Dr. FLUKER: Right. Right. And for Martin Luther King Jr., of course, this is so relevant.

LAWTON: According to some reports, King carried the book during his civil rights protests. King particularly connected to Thurman’s teachings about nonviolence as a way to overcome evil. King interacted with Thurman while studying at Boston University. In 1953, Thurman had become dean of BU’s Marsh Chapel, the first African-American academic dean at a predominantly white university. In correspondence and meetings, Thurman supported King’s efforts, but urged him and other civil rights leaders to maintain a spiritual life.

Dr. FRANKLIN: Dr. Thurman began to challenge these clergy never to lose their rooting in spiritual practices such as meditation, prayer, singing, celebration, and worship and silence. That was an unusual note to have sounded during the rancor of the civil rights movement.

Dr. MARTIN E. MARTY (Professor Emeritus, University of Chicago): I think his best contribution was his ability, before many other people were doing it in our culture, to bring together the inner life, the life of passion, the life of fire, with the external life, the life of politics.

LAWTON: Some activists criticized Thurman for not personally marching or getting more visibly involved in the civil rights struggle.

Dr. FLUKER: I think the exact statement was, we thought he would become, he would be the Moses of our people, but now he’s gone into this mystical stuff.

LAWTON: Thurman believed social change would only come through personal transformation and spiritual disciplines such as meditation.

Dr. MARTY: At the time Howard Thurman began writing and stressing the mystical side it was very rare to even use the language of it in our culture. He was able to go deep inside himself and reach out and teach other people how to transcend the limits of their own, I’ll call it, practical existence.

LAWTON: Another life-long theme for Thurman was bringing people together across racial, cultural and religious lines. In 1944, he co-founded the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco, the nation’s first intentionally interracial, interdenominational church.

Dr. HOWARD THURMAN (speaking at 1979 Howard Convocation): The sense of community, then, seems to me to be a part of the creative intent of the creator.

LAWTON: Today, Thurman’s books are being re-released, and his work is getting new attention.

Boston independent filmmaker Arleigh Prelow is producing a documentary about Thurman.

ARLEIGH PRELOW (InSpirit Communications): Well, I have always heard this: that Thurman’s message is both timeless and timely, as people are wondering, how can I work with this person in the workplace that comes from a totally different culture? People in religion, how can I really acknowledge this person’s faith yet maintain my own? And Thurman was really addressing and wrestling with those issues throughout his life.

LAWTON: Others agree Thurman may be more relevant than ever. In the days after September 11, Robert Franklin says he found himself turning again to the classic Thurman book MEDITATIONS OF THE HEART.

Dr. FRANKLIN (reading from MEDITATIONS OF THE HEART): “Life goes on. Over and over we must know that the real target of evil is not destruction of the body, the reduction to rubble of cities; the real target of evil is to corrupt the spirit of man and to give to his soul the contagion of inner disintegration. To drink in the beauty that is within reach, to clothe one’s life with simple deeds of kindness, to keep alive a sensitiveness to the movement of the spirit of God in the quietness of the human heart and in the workings of the human mind — this is, as always, the ultimate answer to the great deception.” Powerful.

LAWTON: Sounds as if it could have been written on September 12.

Dr. FRANKLIN: Indeed. And this is the voice of the pastor, speaking to the desolation of the city, to ground zero, to wherever evil has touched innocent life.

LAWTON: Franklin says the nation that came to embrace Martin Luther King, Jr. would also benefit from embracing his spiritual mentor, Howard Thurman.

I’m Kim Lawton in Atlanta.