Juvenile Justice System

BOB ABERNETHY (anchor): Now another ethical question: Should a boy — even a boy who has murdered someone — be put into a prison with men? Advocates of mandatory sentencing caution that these kids must be taken off the street and kept off. Critics warn that a young person spending his formative years in an adult prison has much less of a chance of ever becoming a productive citizen.

Lucky Severson reports on the moral questions that arise when adult justice is imposed on juveniles.

LUCKY SEVERSON: This is Jeremy Armstrong, growing up in the Wisconsin State Correctional Institution, a maximum security prison for adults. Jeremy was 16 when he arrived here.

JEREMY ARMSTRONG: There is no way to describe it. You come here and there are a thousand grown men. I mean, they are three times your size. You know, it is just indescribable.

SEVERSON (to Armstrong): Did they say things to you?

ARMSTRONG: “You going to be a bitch.”

SEVERSON: You must have been very scared?

ARMSTRONG: The fear, it is more than fear. It is like humiliation, shame. You just want to die. That’s what I wanted to do. I just wanted to slit my wrist and die.

SEVERSON: When he was 15, Jeremy shot and killed a man during an attempted robbery. Even though a juvenile, he was sentenced as an adult to 20 years in prison for reckless homicide.

Milwaukee District Attorney Micheal McCann says Jeremy Armstrong was tried as an adult, because as a juvenile he would have only been locked up for three years. And even as an adult, he will be eligible for parole in five.

MICHAEL McCANN (District Attorney, Milwaukee, WI): I think it is terribly tragic. I do think he is a young man with fine potential. But to say that five to seven years is excessive, I think is unreasonable. You’re not going to be living next door to him.

SEVERSON: Robin Swellows is Jeremy Armstrong’s attorney.

ROBIN SWELLOWS (Attorney): In many, many instances, I have seen the prosecutors and the judiciary take pleasure in putting kids in adult prison. There is something that says “Aha! They are far, far away from us and to hell with them.”

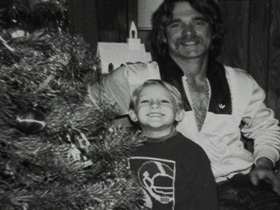

SEVERSON: Jeremy Armstrong was a good student, almost straight A’s, and by all accounts, a good kid.

ARMSTRONG: School was great. It was like my release.

SWELLOWS: He went to school to escape and he worked hard, hard, hard at school and when he got home his world had fallen apart.

SEVERSON: At home, his mom was hooked on prescription drugs, but Jeremy was very close to his dad.

ARMSTRONG: We went fishing. We went to Canada. He coached my little league team when I was in high school. Some guys had a best friend to hang out with. That was my dad.

SEVERSON: Then his father got in an accident, lost his job, and got hooked on crack.

ARMSTRONG: We didn’t have electricity. We didn’t have food. I just needed the money.

SEVERSON: So he held up his father’s crack dealer. They struggled, and Jeremy shot the man.

ARMSTRONG: Bad isn’t the word. I did the worst thing a human being can do.

McCANN: If you are over ten in the state of Wisconsin and commit first degree intentional homicide, or are charged with that, it must start in the adult court.

SEVERSON: But when does a child or an adolescent become an adult? When are they old enough to understand what they’ve done — to understand the charges against them?

Vincent Schiraldi is president of the Justice Policy Institute.

VINCENT SCHIRALDI (President, Justice Policy Institute): A 13 or 14 year-old isn’t responsible for their behavior the same way a 30 year old is. That’s why we don’t let them drive. That’s why they can’t get married. That’s why they can’t vote and that’s why they can’t drink alcoholic beverages. Why all of a sudden, when they commit an irresponsible act, they are as culpable and able to understand ramifications of that as an adult is?

SEVERSON: Last year, 200,000 juveniles in the U.S. were adjudicated as adults, a number that has been increasing every year since the mid 1990s.

Ken Hodges is the District Attorney in Dougherty County, Georgia.

KEN HODGES (District Attorney, Georgia): We’ve had a decrease in juvenile violent crime since 1997. I don’t know that I could attribute it directly to Senate Bill 440 and the prosecution of juveniles as adults, but I think that it has had an impact.

SEVERSON: The Georgia legislature made it mandatory that kids be tried as adults if they commit specified violent crimes. No exceptions.

Take the case of Dantavious Lowe, put in Georgia’s adult prison at Alto for armed robbery when he was 15.

LOWE: We’re doing 10 years, but we are not learning there from it. The only thing we are learning is more violence, because that’s all we really around.

SCHIRADLI: When you put them in the adult system, it is tantamount to giving up on them.

SEVERSON: Despite the harsh environment of an adult prison, Dantavious has earned his high school equivalency and started reading the bible and attending church services. If Dantavious had been tried as a juvenile, he could have been sentenced to a boot camp and subjected to military style discipline, or a juvenile detention center that focuses on rehabilitation. But over the past 20 years, funding for adult prison rehabilitation programs has dwindled to a trickle.

SCHIRALDI: Kids come out of adult institutions every day in America and stick your friends up, steal their cars, break into your house. They are doing it ever day. This is not a problem we are going to face in the future. It is happening right now.

SEVERSON: A study of 5,000 inmates in Florida found that kids that went through the adult system were rearrested 50 percent more often than kids who passed through the juvenile system.

LOWE: Do you think society would just as soon lock you up in prison and throw away the key? Sometimes I do. You know, sometimes maybe even my own family.

SEVERSON: Christopher Manning is in the alto prison for holding up employees at a fast food drive-in. Under the law, his sentence of 10 years was mandatory. He believes that some kids, not all, should be prosecuted as adults.

MANNING: There are some kids, they ain’t never going to change. But then there are some kids, they make mistakes. They will to change, but they don’t see it like that.

SEVERSON: His public defender James Michael, says many lawyers believe that mandatory sentencing has gone too far.

JAMES MICHEAL (Public Defender): Was 10 years too long for Chris Manning? I think 10 years is too long for all of these kids. These will be their life experiences. Their formative years are going to be spent in prison. I find it very hard to believe that kids are going to come out with positive life experiences, ready to go back into society and be productive citizens.

HODGES: Our philosophy has always been that lengthy prison sentences and prison is a deterrent. I don’t believe that we can excuse criminal activity especially of this nature in someone just because they’re 13. I knew when I was 13 that it was not proper to rob someone with a gun or to shoot someone.

SEVERSON: The public perception is that juvenile violent crime is rampant — that high schools have become shooting galleries. In Florida, a 12 year-old guns down a popular teacher — in Arkansas, two young boys target practice with their classmates. These are high-profile tragedies, but they do not appear to be part of a trend.

At the same time prisons are filling with kids, the juvenile crime rate is down nationwide in the last six years. Some prosecutors say it’s because of the tougher laws, but statistics don’t support that. In some cases, states with the toughest laws have the worst juvenile crime rates.

Altogether, 47 states have made it easier to punish kids as adults since 1992.

SCHIRALDI: During the 1990s, politicians really picked up on the ability to make hay out of juvenile crime. The ability to pander and to mine the issue for votes. I think they caught on that you could gain higher office on the backs of kids.

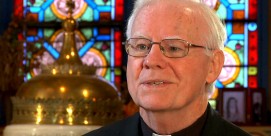

Bishop RICHARD SKLBA (Auxiliary Bishop, Milwaukee): I am troubled by the way in which politicians will use the issue for election or re-election.

SEVERSON: Bishop Richard Sklba, the Auxiliary Bishop of Milwaukee, tried to convince the judge to try Jeremy Armstrong as a juvenile.

Bishop SKLBA: The Bible gives us some direction about encouraging rehabilitation, about turning one’s life around. I think Americans are operating out of fear. And consequently, think that putting people out of circulation is going to help. But it doesn’t help in the longer range of rehabilitation and training to create a better world.

SEVERSON: Bishop Sklba still visits Jeremy Armstrong in prison. Jeremy could be paroled in about a year if he can get a college to accept him.

But under Georgia law, Dantavious Lowe and Chris Manning are not eligible for parole.

MANNING: What is the worst part of being here? You are missing everything. Even if it is going to a high school. I never been to a prom. Going to the prom. You see that on TV — or going to a football game. You’re just missing it. You’re missing out on all of it.

SEVERSON: Chris and Dantavious will be released when they’re in their mid 20s. Many Americans think they got what they deserved. But critics say the price is often too high — for kids, and for the society they will be ill-prepared to enter when they get out.

I’m Lucky Severson for RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY in Alto, Georgia.