In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Father Damien’s Legacy

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: For the past 50 years, many churches and health organizations have observed the last Sunday in January as the World Day of Leprosy. Hansen’s disease, as it’s also known, is now curable, but it still strikes a quarter of a million people each year. Remembering leprosy victims recalls the life of Father Damien, a Belgian priest who cared for the outcasts in a leprosy colony in Hawaii, and who eventually died of leprosy himself. Father Damien is expected to be named a saint later this year [Editor’s note: Father Damien will be canonized in Rome on October 11, 2009] and Lucky Severson tells his story.

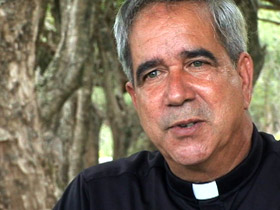

LUCKY SEVERSON: This place may look like a slice of heaven, but to many who lived here it was hell on earth. This is Kalaupapa, which was and still is a leper colony on the Hawaiian island of Molokai. It is an extremely isolated place, forgotten by the civilized world for over 100 years. That may soon change because of the honor about to be bestowed on a priest long ago who helped the diseased of Kalaupapa when no one else would. His name was Father Damien de Veuster, a missionary priest from Belgium. He is remembered by another Catholic priest, Father Clyde Guerreiro.

Father CLYDE GUERREIRO: It’s the story, the classic story of heroic virtue versus the worst we can be as human beings.

Father CLYDE GUERREIRO: It’s the story, the classic story of heroic virtue versus the worst we can be as human beings.

SEVERSON: Father Damien called the numerous cemeteries on Kalaupapa “gardens of the dead.” Almost all of the 8,000 souls buried in these gardens were victims of Hansen’s disease, also known as leprosy. Its victims were first exiled here beginning in 1866, forcefully separated from their loved ones, treated as criminals, literally thrown off the boat near this rocky beach.

Fr. GUERREIRO: The schooner would park out there, and they’d just throw them over, and if they survived, well, then they lived here.

SEVERSON: When Father Damien arrived in 1873, those thrown from the boat — the castaways — lived under the most primitive conditions, without potable drinking water, in shacks they constructed out of sticks and dried leaves. Food was scarce. Doctors would occasionally leave medicine but refuse to touch the patients. Survival was all that mattered, and the place became a lawless wild land. Father Damien would change all of that. Father Lane Akiona grew up on Molokai, and grew up admiring Father Damien.

Father LANE AKIONA: He was the builder. He was the coffin builder. He was the grave digger. He did the services. He anointed them. He was their nurse and doctor. He did practically everything for them.

Father LANE AKIONA: He was the builder. He was the coffin builder. He was the grave digger. He did the services. He anointed them. He was their nurse and doctor. He did practically everything for them.

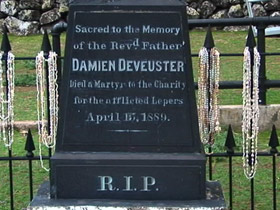

SEVERSON: And when Father Damien was 49, he died for them, a victim of leprosy. He had simply treated too many sores and infections. His grave is located next to a church he preached in. Most of those buried on Kalaupapa died in the early 1940s, before the new sulfone drugs were developed that controlled the infectious disease and stopped its contagion. Still, it wasn’t until 1969, a quarter of a century later, that the law ordering forced exile was finally lifted. Dr. Walter Chang says victims of Hansen’s disease have always been treated with callous disregard.

Dr. WALTER CHANG: From the Bible and from historical accounts, leprosy was considered a very ghastly disease. Lepers were detested. They were stoned. They were even killed.

SEVERSON: Today, there are only about 20 patients living in Kalaupapa where there is now a hospital, and care is always available for those still afflicted with the disease. They were sentenced here. Some don’t need to stay here any longer, but they do. Others stay because they can’t leave the stigma behind. Melly Watanuki has been here since 1969 because it’s her home.

SEVERSON: Today, there are only about 20 patients living in Kalaupapa where there is now a hospital, and care is always available for those still afflicted with the disease. They were sentenced here. Some don’t need to stay here any longer, but they do. Others stay because they can’t leave the stigma behind. Melly Watanuki has been here since 1969 because it’s her home.

(to Melly Watanauki): Are you still sick?

MELLY WATANUKI: No.

SEVERSON: But you have to take medicine every day, right?

Ms. WATANUKI: Yeah, that was way before when I would get sick, I got to take the medicine for cure.

SEVERSON: But you don’t have to take the medicine anymore?

Ms. WATANUKI: No.

SEVERSON: The place is still almost as inaccessible as it was in the 1800s. No one is allowed in without government permission. There are only two ways onto the peninsula: an up-and-down eight-minute flight over the worlds tallest sea cliffs, which separate the colony from the outside world, or a steep mule train ride down from what is known as topside. Audrey Toguchi, a retired schoolteacher, has made the journey from her home in Honolulu five times, always to pray at Father Damien’s gravesite.

AUDREY TOGUCHI: Oh, he’s helped me a lot. He really has. And so how else can I look at him but as my hero?

AUDREY TOGUCHI: Oh, he’s helped me a lot. He really has. And so how else can I look at him but as my hero?

Dr. CHANG (pointing to x-ray): See how vicious it looks? They look like all kinds of different criminals.

SEVERSON: If Father Damien was Audrey’s hero before, she’s convinced he became her lifesaver after Dr. Walter Chang, a general surgeon, diagnosed her with a very rare kind of aggressive cancer of the fat tissues 10 years ago.

Dr. CHANG: You know, I told her, “You need chemotherapy. Without chemotherapy,” I said, “the likelihood of you surviving a long time is extremely small.”

(to Ms. Toguchi): How long did he give you to live?

Ms. TOGUCHI: Well, probably about five or six months.

Dr. CHANG: Well, she told me very calmly, “Doctor, I’m not going to accept chemotherapy. I’m going to Molokai to pray to Father Damien.” And I replied, “Mrs. Toguchi, prayers are very nice, but you still need chemotherapy.” And she said, “Doctor, I’m going to pray only.”

Dr. CHANG: Well, she told me very calmly, “Doctor, I’m not going to accept chemotherapy. I’m going to Molokai to pray to Father Damien.” And I replied, “Mrs. Toguchi, prayers are very nice, but you still need chemotherapy.” And she said, “Doctor, I’m going to pray only.”

SEVERSON: And so Audrey made one more trip to Father Damien’s grave, and here’s what she said.

Ms. TOGUCHI: “Father Damien, I have all these problems, and I really need your help to intercede, and dear Lord please, please help me.”

Dr. CHANG (pointing to x-rays): OK, this is Mrs. Toguchi’s x-ray before she went to Molokai. This is the cancer spread to her lungs.

SEVERSON: But after she returned from Father Damien’s graveside, the x-rays showed her cancer was receding. Eventually it disappeared altogether.

Ms. TOGUCHI: And Dr. Chang said, “What did you do?” I said I asked Father Damien for help.

Dr. CHANG: I said to myself, “This is a very remarkable event. It has never happened before in as far as I can detect from the history of medicine.” So I said to myself, “You know, Mrs. Toguchi,” I said, “this is so remarkable you ought to report it to your — people in your religion.”

SEVERSON: So Mrs. Toguchi contacted the Vatican and sent along Dr. Chang’s meticulously detailed record of her recovery, which was thoroughly investigated by church authorities, who eventually declared it a miracle. Now Father Damien is scheduled to become, officially, Saint Damien.

SEVERSON: So Mrs. Toguchi contacted the Vatican and sent along Dr. Chang’s meticulously detailed record of her recovery, which was thoroughly investigated by church authorities, who eventually declared it a miracle. Now Father Damien is scheduled to become, officially, Saint Damien.

Dr. CHANG: The true skeptic will call this a random coincidence. The true believer, the truly faithful, will call this a miracle. I think I’ll have to straddle that line and call it a complete spontaneous or complete and permanent spontaneous regression of cancer.

SEVERSON: The canonization process is not quick or easy. Father Damien was first officially venerated for his work in Kalaupapa over 100 years ago. Then, to become a saint, he needed to perform two miracle healings authenticated by the best science of the times. The first, many years ago, was a French nun. The second, in 1999, was Audrey Toguchi.

The news that Father Damien was going to become Saint Damien did not come as a surprise to the patients still living here. To them, he’s always been a saint, one who would not recognize Kalaupapa today. The place seems like an island paradise with well-groomed bungalows, a grocery store, and gas station. It’s a quiet place, but that may change after the Vatican formally canonizes Father Damien.

The news that Father Damien was going to become Saint Damien did not come as a surprise to the patients still living here. To them, he’s always been a saint, one who would not recognize Kalaupapa today. The place seems like an island paradise with well-groomed bungalows, a grocery store, and gas station. It’s a quiet place, but that may change after the Vatican formally canonizes Father Damien.

SEVERSON: Kalaupapa has always been considered a special place. There are stories of natives making spiritual pilgrimages here 500 years ago. Clarence and Ivy Kahilihaiwa have been here more than 50 years, and they agree with their ancestors.

(to Clarence Kahilihiwa): Is this a spiritual place here?

CLARENCE KAHILIHIWA: It is more than that. The “manna,” the spirit is here, I guess, because of our ancestors who died here way back.

Fr. AKIONA: To know that so many people went there, feeling helpless — no sense of hope. And here comes this missionary from a foreign land and was willing to do everything for them. It is a spiritual place.

SEVERSON: As long as there are patients here, the government will continue to restrict the number of visitors. But the patients are getting older. The youngest is almost 70, and when they’re gone, only the “gardens of the dead” will speak of Kalaupapa’s dark, painful history.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson in Kaluapapa, Hawaii.