In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Inner-City Funeral Director

LUCKY SEVERSON, correspondent: The middle-aged woman cleaning up the big motorcycle is Charlene Wilson-Doffoney who’s on her way to work at her funeral home in South Philly. She says she took up cycling to get away from the dying. Philadelphia may be best known as the City of Brotherly Love, but Charlene says her neighborhood has also been called “Killadelphia” because there have been so many murders, so many young victims of drive-bys, gang warfare, drug deals gone bad, and simple disagreements—333 killings overall in 2008.

CHARLENE WILSON-DOFFONEY: A little boy got shot.

SEVERSON: A little boy got shot right here?

WILSON-DOFFONEY: Well, yeah. This park here, it is named after a young man who got killed as well.

SEVERSON: Did you bury him?

WILSON-DOFFONEY: We did him. We did Hanna. I just passed his family home around the corner.

SEVERSON: Why do you do this? It just seems to be so sad to do this.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: Well, I am a caregiver to their family. I watch over their children that passed away. My job is to protect them.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: Well, I am a caregiver to their family. I watch over their children that passed away. My job is to protect them.

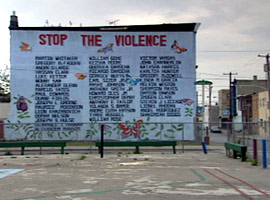

SEVERSON: She knew a lot of the victims whose names are on the mural. She buried a number of them. She buried her brother-in-law who was murdered recently. She buried the three sons of a close friend. She’s buried so many gun-shot victims she tore up her own gun permit. One funeral she recalls in particular.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: I remember breaking down because I was tired of seeing young boys get killed, and you tell the young men, they don’t get it, that we tired. They just don’t know the pressure for a mother. When I see that mother who lost her son I wish I could bring him back. I wish I could bring him back to her. I wish that they got a better chance.

SEVERSON: Police say fourteen-year-old Tykeem Law was shot by an eighteen-year-old who was angry because Tykeem didn’t move his bicycle out of the way fast enough.

(speaking to Wilson-Doffoney): You like to have these young men be there while you are preparing the body and serving as pall bearers.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: Yes. I don’t think they know it’s real. They think they get back up, and I remember somebody dying near the funeral home, like man “get up, get up.” Well, they’re not going to be back up. They don’t get back up.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: Yes. I don’t think they know it’s real. They think they get back up, and I remember somebody dying near the funeral home, like man “get up, get up.” Well, they’re not going to be back up. They don’t get back up.

SEVERSON: Charlene says she got the call to be an undertaker when she was 23 and a single mom with a very dim future. Although it’s been a difficult struggle, she now owns her own funeral parlor. She is a woman of abiding faith, but rather than preach to kids in the hood, she tries to lead by example.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: Because I am a believer. My job is to witness. Every day I walk I am a witness as you get a chance to tell somebody that they can make it. The thing for me in South Philadelphia is to let young people know if I can do it, you can, too.

SEVERSON: Even in the worst of the neighborhoods, kids treat Charlene with respect, partly because they know that she will treat them with respect in death and she will look after their moms. None of these young men grew up with a father in the home. Some have been in prison. Some have dealt drugs. All have a friend or relative who has been murdered.

(speaking to group of young men): What do you want to be in 10 years? Where do you think you are going to be?

TROY: I want to be alive.

TROY: I want to be alive.

SEVERSON: A lawyer?

TROY: Alive.

SEVERSON: So you mean you get up a lot of times and say I hope I live through the day?

GROUP OF YOUNG MEN: Yes.

TROY: You don’t know what’s going to happen to you, because half the people around here just shoot at whoever, daytime, nighttime, it don’t matter when they do it, and you don’t know when you’re going to be hit or you’re not going to be hit.

KEVIN: Any day could be your day. I see people walk by me, they get up two blocks away you see them laying out there bleeding.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: I think it goes by what you see. When I see my young boys on a corner, they want to see better but nobody takes them anywhere to see anything else.

SEVERSON (speaking to group of young men): Do you have a responsibility with these kids who are 15 and 14 that Charlene is burying? Do you try to talk to them, or what do you say to them?

SEVERSON (speaking to group of young men): Do you have a responsibility with these kids who are 15 and 14 that Charlene is burying? Do you try to talk to them, or what do you say to them?

BYIEME: It is just like talking to a brick wall. You can talk but they ain’t going to listen.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: They plan for their funeral. They know. Some people do come to me and say Miss Charlene, you got me? And I am like yeah, I got you.

KEVIN: A lot of them say when I get buried I want to have this on, I want to have that on. They say at my funeral I’m going to have all the girls there.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: And you are like is there anything I can do? Can I turn you around a different way or anything, and they know that they are going to go down.

SEVERSON: The kids themselves agree that too often their problems begin at home.

NEIL: Most of these parents just run around and worry about themselves now. They didn’t want to have kids and then once they have the kid, they just let him go. They had these kids to get on welfare. They ended up with the easy way out.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: I get a chance to come into the prison a lot, and I see all them black men. Who is there for the black boy? The fathers that you see are in jail, and the kids are raising their selves, and the mothers, they got their own issues going on—not having the man around, having to provide, and they don’t have jobs.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: I get a chance to come into the prison a lot, and I see all them black men. Who is there for the black boy? The fathers that you see are in jail, and the kids are raising their selves, and the mothers, they got their own issues going on—not having the man around, having to provide, and they don’t have jobs.

SEVERSON: Reverend Edward Winslow ministers to the young people in the neighborhood. He says parents and their kids have stopped coming to church, so it’s difficult to reach them.

REVEREND EDWARD WINSLOW: And where we would be able to teach the kids about character building, we don’t do it anymore because they are not there anymore.

SEVERSON: Charlene says there is plenty of blame to go around—broken families, no jobs, no role models, and ministers who are missing in action.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: You have a lot of ministers today who don’t care. They don’t evangelize anymore. They are not out to save souls. They don’t care about the loss as long as it doesn’t affect them.

SEVERSON: Reverend Winslow cares about these kids, but too often he gets to know them after it’s too late.

REVEREND WINSLOW: I see more now lately in the end than in the beginning or in the middle, and that’s a sad thing. That’s what keeps this place running, the death. That’s her business, it is true, but the point is how do we get to them before that?

WILSON-DOFFONEY (speaking to police): I think the other day there was a shooting.

SEVERSON: The police, the grieving moms, the kids—they all know Charlene, but not always the way she wants them to know her.

WILSON-DOFFONEY: I know where I’ve been, and if it worked for me, the little girl from North Philly that didn’t know how she was going to make it, it will work for them, and I am just hurt to see the kids that don’t know that it works.

SEVERSON: The crime rate in South Philly has been going down. The mayor says it’s because there are more police on the streets and more citizen involvement. The business of burying is less brisk than it once was. So Charlene can spend more time doing what she would rather be doing.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly I’m Lucky Severson in Philadelphia.