Rev. William Abernethy and the Ethics of Cloning

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Many scientists say the most promise for curing various diseases is to clone human embryos. Not clone them to create a new human being, reproductive cloning, but clone them to cure the sick; therapeutic cloning. But therapeutic cloning is sharply controversial because it destroys the original human embryo, and that, say many ethicists, is taking a life.

Lucky Severson reviews the therapeutic cloning debate, and let me acknowledge a strong personal interest in it. The man who wants so much to have medical help is my first cousin.

LUCKY SEVERSON: It’s a familiar scene in Wenhem, Massachusetts: The Reverend Ann Abernethy, walking beside her husband, the Reverend William Abernethy, to the church where she is the pastor. Both are United Church of Christ pastors. He has suffered from Parkinson’s disease for 20 years.

Reverend WILLIAM ABERNETHY: It makes me furious to have that disease; to wake up in the morning and find yourself shaking so that you can’t do what you want to do; to find yourself adjusting to a new inability to work and walk and talk and laugh.

SEVERSON: He says he will try anything that offers hope. He’s had two brain operations, which have worked for some patients, but not for him. Now he is holding onto the hope offered by therapeutic cloning. And in Reverend Abernethy’s view, it is research that has God’s blessing.

Rev. ABERNETHY: To have a possibility to make human life better and not use it is as much sin as anything I can think of. Denying what God has made available to us, the abundant life Christ promises, is transgressing what God has called us to be.

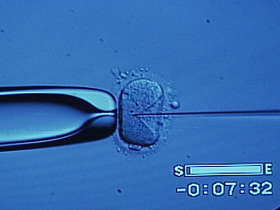

SEVERSON: For all its mystery, therapeutic cloning is not a scientifically complicated process, at least in its initial stage. Researchers remove the nucleus of a woman’s egg and replace it with a cell from the patient. The egg is then placed in a Petri dish and the cell in it is stimulated to divide for five days. It’s these cloned embryonic stem cells that have the potential, scientists believe, to cure a variety of diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s and other illnesses. The cells would be implanted without the patient’s body rejecting them.

So the embryo is first created and then destroyed to obtain the needed stem cells, and that worries Leon Kass. He’s chairman of the President’s Council on Bioethics.

Dr. LEON KASS (Biologist and Chair, President’s Council on Bioethics): Judaism, which is my religion, does not believe that this is a human being, but as a biologist, I’ve come to somehow regard the earliest stages of human life as not humanly nothing. It’s something, and if nothing obstructs its unfolding itself [it can] become something like you and me, if all goes well.

SEVERSON: And Leon Kass is not alone. Theology professor Gilbert Meilaender at Valparaiso University is on the President’s Council. He believes the tiny cloned embryo is a human life and deserves protection.

Professor GILBERT MEILAENDER (Theology Department, Valparaiso University): The simple fact that someone is little and undeveloped at this point doesn’t mean that they somehow lack equality and dignity with someone who is big and strong and smart.

SEVERSON: Many, if not most scientists take a different point of view. Dr. George Daley is a stem cell expert with the Whitehead Institute at MIT.

Dr. GEORGE DALEY (Whitehead Institute, MIT): We are talking about embryos that are smaller than the period at the end of a sentence — the cells that exist as individual elements in the Petri dish. Cells that I can extract from your skin and place in a Petri dish and reactivate. I don’t think those are beings.

SEVERSON: Meilaender the theologian compares the vulnerability of an embryo to that of Christ on the cross. He believes those among us who are suffering, such as Reverend Abernethy, deserve help, but not if the moral cost is too high.

Prof. MEILAENDER: Suffering is a terrible thing and we must relieve it as much as we can, but who would want to live in a society which thought that the relief of suffering was the highest good, and that one ought never accept suffering in order to achieve some other goal? I wouldn’t think that would be a very noble society at all.

Rev. ANN ABERNETHY (First Church in Wenham): Is that not the higher good, that we need to take the lives that we are kind of committed to care for and to do the best we can to provide quality of life for them, as opposed to putting our weight on the lives that aren’t viable yet?

SEVERSON: It’s also what’s down the road of genetics that concerns Gilbert Meilaender.

Prof. MEILAENDER: What we really have would be a whole industry of cloned embryos that we produced to use as raw materials for our research, and that would worry me in its own right but also because… it would lead to reproductive cloning.

SEVERSON: It didn’t help alleviate those fears when the renegade doctor Severino Antinori in Italy announced that he plans to clone five human babies by the end of the year.

The vast majority of Americans are strongly opposed to reproductive cloning, but most support therapeutic cloning. President Bush opposes both types and announced his beliefs even before his council went to work.

President GEORGE W. BUSH: Anything other than a total ban on human cloning would be unethical. Research cloning would contradict the most fundamental principle of medical ethics: that no human life should be exploited or extinguished for the benefit of another.

SEVERSON: Last year the House of Representatives approved a bill that would criminalize all forms of cloning, the first time in this country scientific research has ever been totally banned. And then a bill in the Senate sponsored by Kansas Senator Sam Brownback promised the same total ban.

Senator SAM BROWNBACK: The principle being denied in this case is the dignity of the young human, effectively making the human embryo equal to mere plant or animal life or property.

Dr. DALEY: Well, obviously if there’s a criminalization of research on these very, very early stages of human embryos or on the use of nuclear transfer, cloning to create these human embryos, this very promising new area of biomedicine will not go forward in the U.S.

SEVERSON: But the momentum started to shift when Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, a Mormon, whose church opposes cloning, said he would co-sponsor a bill that would allow some forms of therapeutic cloning.

Sen. ORRIN HATCH: I believe a human’s life begins in a womb, not in a Petri dish or a refrigerator.

SEVERSON: So for Reverend Abernethy and the others with diseases that might be cured, the prospect of therapeutic cloning stays alive, but not without serious opposition.

Dr. KASS: There is Alzheimer’s in my family, and all the stars are that it’s in my future. I am not cavalier about what’s at stake here, but it’s also — it seems to me very important that we pursue these means, these cures in a way that doesn’t cheapen the kind of life that we have to live longer in.

Dr. DALEY: Therapeutic cloning, I believe, is not dehumanizing. I believe it is using a technology to treat real patients, patients in need.

SEVERSON: For the opponents the argument almost always goes back to protecting the tiny embryo they see as a human life, and what would happen to our society if we allow therapeutic cloning.

Prof. MEILEANDER: I think it would diminish us. It would suggest a kind of crassness, a willingness to use nascent human life simply as a resource for our purposes.

Rev. ANN ABERNETHY: I don’t see human science as separated from God. That’s God’s gift, and caring is God’s gift, and compassion is God’s gift.

SEVERSON: For Reverend Abernethy, the hope that’s dangling out there was put there, he has come to believe, by a compassionate God.

Rev. WILLIAM ABERNETHY: What I found myself saying, in spite of myself, was, “God, if you could heal me, why didn’t you?” And that anger was very difficult for me to deal with for several months. For the most part that is lifted. It’s almost as though God would say things to me which made sense rationally, but he said it in a tone of voice that was immensely compassionate. And that’s been very important to me, that kind of experience. It makes me feel deeply a part of God’s love. So whatever happens in the next few years — stem cells or whatever — I will celebrate it, I hope.

SEVERSON: The celebration for Reverend Abernethy, and the millions like him who are waiting, is years away at the very earliest. For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Lucky Severson in Wenham, Massachusetts.