Tibetan Buddhists in Exile

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, Part Two of our series on the Tibetan Buddhists in exile in India. They’re refugees not only from Chinese oppression in Tibet but also from what the Dalai Lama calls “cultural genocide.” How can the Tibetan refugees preserve the prayer wheels and mandalas of their culture and pass on those traditions to a new generation increasingly influenced by the West? And can the Tibetan Buddhists in exile really expect someday to go home? Our correspondent is Lucky Severson.

LUCKY SEVERSON: A Tibetan monk calling the faithful to an evening session of prayer and meditation under the gaze of the majestic Himalayas. But this is not Tibet. It’s a remote corner of neighboring India where the Tibetan people, headed by His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, are putting down roots, albeit shallow roots, in the hope of one day returning to their homeland.

The tranquility of these re-created sacred spaces is in sharp contrast to the noise and jumble of Tibetan commerce on the other side of town, a dusty hillside village called Dharamsala.

Dharamsala is more than just a refuge for all the Tibetans who make the dangerous journey across the Himalayas to escape Chinese oppression. It’s a place where dreams and memories come together. There is a sense of urgency and purpose here, to hang on tight to the past, get ready for the future, wherever that might be.

Jeremy Russell is a writer who has lived in Dharamsala for 20 years.

Mr. JEREMY RUSSELL (Writer): It’s easy to forget that when they came out of Tibet, they had nothing. They just had what they carried out with them.

SEVERSON: It was 1959. After nine years of brutal Chinese occupation, the 14th Dalai Lama, fearing for his life, escaped to India, where he was given refuge in a backwater dead end in the foothills of the Himalayas, the wrong side of the Himalayas, but nonetheless a home.

Tibetan refugees still arrive almost every day, desperate to get away from the starkly beautiful land they love, but a land now unbearable to them under Chinese rule. Jamyang Norbu is a Tibetan writer and scholar.

Mr. JAMYANG NORBU (Tibetan Scholar and Writer): People there with binoculars and telescopes, watching everyone passing up and down. So it is really, really tightly controlled as far as security is concerned.

SEVERSON: Over a million Tibetans killed by the Chinese, 6,000 monasteries destroyed, secret police everywhere. But in recent years, the methods are less brutal, more sophisticated. The Chinese are diluting the culture, flooding Tibet with 7.5 million Chinese compared to 6 million Tibetans.

Mr. NORBU: They’ve created a totally materialistic culture. You have discotheques; you have karaoke bars.

SEVERSON: Even the Dalai Lama, who has always treated China with what his followers call a kind heart, says whether it is deliberate or not, the Chinese are destroying the Tibetan culture.

DALAI LAMA: Whether intentionally or unintentionally, some kind of cultural genocide is taking place.

SEVERSON: Dharamsala has become the cultural heart and political nerve center of the Tibetan people. The government in exile has established many ministries and a parliament.

Mr. RUSSELL: Their identity’s under threat. They’re — the people who are here in exile are very aware that if they don’t preserve the traditions that have been handed down to them, then they’re going to be lost.

SEVERSON: Here at the Norbulingka Institute, young artists are learning old art forms no longer taught in Tibet. When this statue of the Tibetan Buddhist deity Kalachakra is completed, it will appear at a Tibetan center in New York. Preserving the past is one thing; living in the past is another.

Mr. NORBU: I totally disagree with the whole Tibetan establishment of preserving culture. I don’t want it to be preserved so that, you know, like, in the future, anthropologists and western visitors come here and see us in our reservation doing our rain dance. I want Tibetan culture to continue into the past but, at the same time, being able to be — to operate in the 21st century.

SEVERSON: The monasteries and nunneries here do teach ancient traditions like creating sand mandalas, but the nuns can also pursue a higher education to achieve status equal to a monk, something impossible in Tibet.

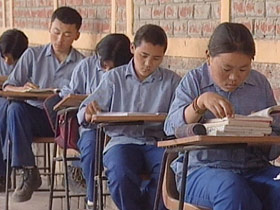

In Tibet, schoolchildren learn Chinese and Chinese history, but here they receive a traditional Tibetan Buddhist education. The children learn not only their history, but skills for their future.

NIMA: The way I came from Tibet place is a very small village, and it doesn’t know about the Chinese and Dalai Lama and the history of Tibet, since they are really uneducated people. And so I wanted to educate them if I can.

SEVERSON: Like many of the 2,500 kids at the Tibetan Children’s Center, Nima’s family is still back in Tibet. For these kids, going home is an obsession. They are part of a new activist generation determined to make their voices heard.

(Reading) “We are writing this petition to you. The present situation in Tibet is such that we can’t go back to our place of birth, our home.”

They are running out of patience. Young people are also growing up in a western culture, out of the isolation of Tibet. They wear jeans, hang out at the five cybercafes in Dharamsala, and mingle with westerners. Is it possible that the West is corrupting a culture already under attack?

When the Dalai Lama came here, he built less ornate monasteries and vowed to make the rituals more personal and private, but that’s been difficult, partly because of the intense western interest and influence.

Mr. NORBU: Sometimes our teachers seem to be aiming their discourse to the West and to the West in a sense of, let’s say — let me stereotype it — to, let’s say, California.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #1: I mean, it doesn’t feel like India at all. It feels like a completely different country. But it’s nice. It feels like Berkeley, actually.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #2: Yes.

SEVERSON: Feels like what?

WOMAN #1: Like Berkeley.

SEVERSON: The older Tibetans still practice their religion in private and sometimes in the street. The younger ones seem more interested in more temporal things, for now, anyway.

Mr. NORBU: The real problem is right now, because of the demands made by western Buddhists on our society, Tibetan lamas have lit — very little time to preach to their own people. Younger children, especially teenagers, are not getting religious instruction.

SEVERSON: So on one hand, the Tibetans here are spinning their prayer wheels and dreaming of home. The old Tibet exists only in memories. The new Tibet is Chinese. What happens when and if the Tibetans in exile get a chance to go home? So much has changed on this and the other side of the Himalayas in the last 40 years.

ABERNETHY: Lucky, it was a wonderful report. Talking to the Dalai Lama, I know he tells you that he’s going back to Tibet in his lifetime. Could you believe him?

SEVERSON: I’d have a difficult time not believing anything he said, but I don’t understand how it can happen in his lifetime. There’s simply no incentive for the Chinese to give up Tibet.

ABERNETHY: Even if they did go back, what would that mean for Tibetan Buddhism?

SEVERSON: I think that it’s in question, because Tibetan Buddhism, particularly from within Tibet, has changed so much under Chinese rule. I just don’t see how it — if it happens, it’s not going to be easy; it’s going to be very, very difficult.

ABERNETHY: Lucky, many thanks.

SEVERSON: Thank you.