In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Political Buddhism

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: We have a special report today on the plight and paradox of Tibetan Buddhists. They teach nonviolence, but their demonstrations against the Chinese have sometimes become violent. How can they persuade the Chinese that they and the Dalai Lama are not a threat? Lucky Severson reports.

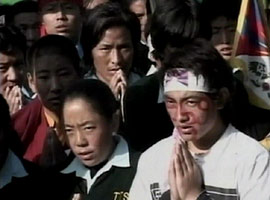

LUCKY SEVERSON: Chinese authorities called these protesters in San Francisco “Tibetan hooligans” whose only purpose was to use violence to embarrass China in its moment of Olympic glory. Lhadon Tethong was there. She’s a Tibetan activist and leader of Students for a Free Tibet.

LHADON TETHONG (Students for a Free Tibet): There has to be tension. There has to be crisis. They have to feel the occupation is a problem for them whether they agree with us or not.

SEVERSON: The protests in San Francisco and around the world were mainly a reaction to demonstrations by Tibetan monks inside Tibet and China. The Chinese government mobilized troops. Many Tibetan monks and nuns were arrested when the initial demonstration began earlier this year in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. The Chinese placed the blame squarely on the leader of some six million Tibetan Buddhists — the Dalai Lama. Columbia University professor of Buddhist studies Robert Thurman says the charge is simply not true.

Professor ROBERT THURMAN (Department of Buddhist Studies, Columbia University): The Chinese are desperate now to try to claim that the Dalai Lama caused all this upset, which of course he totally did not. He was totally upset.

SEVERSON: The work of the protesters is raising questions among Tibetans themselves and people around the world. For instance, will the demonstrations actually force the Chinese to loosen control of Tibetan Buddhism? And how can a religious philosophy built around peace and compassion continue to hold the high ground when the protests are resulting in so much violence? Professor Thurman says the Tibetan devotion to nonviolence goes to the core of their faith –the path to total enlightenment takes place over many, many lifetimes, many reincarnations, and to commit violence threatens that path.

SEVERSON: The work of the protesters is raising questions among Tibetans themselves and people around the world. For instance, will the demonstrations actually force the Chinese to loosen control of Tibetan Buddhism? And how can a religious philosophy built around peace and compassion continue to hold the high ground when the protests are resulting in so much violence? Professor Thurman says the Tibetan devotion to nonviolence goes to the core of their faith –the path to total enlightenment takes place over many, many lifetimes, many reincarnations, and to commit violence threatens that path.

Prof. THURMAN: My life is my own evolutionary moment to progress, and I’m not going to do violence. So therefore, to cherish your own life, you don’t want to risk it for some sort of worldly aim. You want to develop your soul because that’s what your life is for.

SEVERSON: But he says those who think protestors have violated the basic principle of nonviolence don’t understand the Tibetan Buddhist philosophy of self-defense.

Prof. THURMAN: Buddhist ethics is intense about nonviolence, but it’s also pragmatic. There is one sutra where it’s stated if you are invaded by an enemy and you can successfully defend yourself and repel the enemy, and the enemy while occupying you will cause tremendous violence, then you should defend yourself.

SEVERSON: Chinese history professor Tu Weiming of Harvard believes at least part of the problem stems from a lack of understanding by the Chinese leadership of Tibetan Buddhism and the role of the Dalai Lama.

Professor TU WEIMING (Harvard University): The Chinese government is not at all informed about the Dalai Lama as a spiritual leader. They always perceive him as a political leader interested in mobilizing anti-Chinese forces outside of China. My sense is that it’s a misperception that needs to be corrected.

Professor TU WEIMING (Harvard University): The Chinese government is not at all informed about the Dalai Lama as a spiritual leader. They always perceive him as a political leader interested in mobilizing anti-Chinese forces outside of China. My sense is that it’s a misperception that needs to be corrected.

SEVERSON: If any Westerner ought to understand the role of the Dalai Lama among Tibetans, it is Robert Thurman. Before choosing to be a professor, Thurman became the first Western Tibetan Buddhist monk under the tutelage of the Dalai Lama. He says the Dalai Lama is to Buddhism what Jesus is to Christianity.

Prof. THURMAN: If Jesus was constantly coming back, how would Christians feel about that person? You can get an idea of how the Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhists feel about the Dalai Lama.

SEVERSON: But Chinese officials say the looting, the beatings, and destruction of property prove that the Tibetan people and their leader are hypocrites. The Chinese government maintains, and most of its citizens believe, that Tibet has always been a part of China. The Tibetans disagree saying their country didn’t become part of China until 1951 after it was forcefully occupied by Chinese troops. The Dalai Lama fled to his new home in exile in India in 1959.

Prof. THURMAN: For 30 years, from the ’50s to the end of Mao, they did the most violent thing. You can’t even believe it. They killed a million people. Half of it was famine craziness, and a lot of it was this class struggle thing, you know, “kill the landlords,” and political things and eradicating the religion. You couldn’t even have a rosary. You’d go to work camp prison for life.

Prof. THURMAN: For 30 years, from the ’50s to the end of Mao, they did the most violent thing. You can’t even believe it. They killed a million people. Half of it was famine craziness, and a lot of it was this class struggle thing, you know, “kill the landlords,” and political things and eradicating the religion. You couldn’t even have a rosary. You’d go to work camp prison for life.

SEVERSON: Chinese authorities dispute these charges and say China has lifted Tibet into the 21st century.

Prof. WEIMING: China believes that in the last few decades the government has contributed significantly to Tibetan growth in terms of economic growth, in terms of building roads and so forth.

SEVERSON: But many Tibetans say the Chinese government is systematically diluting their culture and religion while encouraging millions of Chinese to move here. The Dalai Lama has called it “cultural genocide.” The Chinese dispute the genocide charge and accuse the protesters of purely anti-Chinese activity. Many of today’s Chinese leaders come from engineering and science backgrounds. Professor Weiming says these leaders are most interested in generating wealth and modernization — that they have a deep skepticism of all religions especially if their leaders threaten authority.

Prof. WEIMING: Tibetans feel they are humiliated, they are ignored, they are marginalized because people don’t understand why they are so devoted to religion, to the Dalai Lama. Their devotion sometimes is wrongly perceived as a kind of superstition and that should be overcome by modernization.

SEVERSON: The Dalai Lama has always preached nonviolence and never demanded independence from China.

DALAI LAMA (during U.S. visit): The whole world knows the Dalai Lama not seeking independence. Our approach is not separation, within the People’s Republic of China for full guarantee about our unique culture and heritage including our language.

DALAI LAMA (during U.S. visit): The whole world knows the Dalai Lama not seeking independence. Our approach is not separation, within the People’s Republic of China for full guarantee about our unique culture and heritage including our language.

SEVERSON: Arjia Rinpoche was a highly positioned Lama in Tibet before he defected to the U.S. 10 years ago. He supports the Dalai Lama’s approach to peace.

ARJIA RINPOCHE (Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center): Most of Tibetans like His Holiness’ idea. You know, the Middle Way works.

SEVERSON: The Middle Way, however, meaning more autonomy and more freedom, is not the ultimate goal of young Tibetans. They want full independence, their leader the Dalai Lama notwithstanding.

LHADON TETHONG: He is like a parent, a senior elder, respected member of the family whom you love and whom I can also disagree at times when I hear him saying something politically that I might not necessarily agree with or like. But that doesn’t change the nature of how much I respect or how much I love him.

SEVERSON: They may love him, but young Tibetans are growing impatient with the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way, and he may be feeling the pressure.

DALAI LAMA (during U.S. visit): If things become out of control then my only option is completely resign.

DALAI LAMA (during U.S. visit): If things become out of control then my only option is completely resign.

SEVERSON: Professor Thurman says if Chinese leaders were willing to meet with the Dalai Lama in person, the conflict could be resolved.

Prof. THURMAN: If I can get him a room with Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, it would have a profound impact actually on the world. They would turn around, I think.

Prof. WEIMING: I was deeply worried when I was in China that not just the government officials, but some intellectuals believe that if the Dalai Lama fades from the scene the problem will be resolved. If the Dalai Lama fades from the scene, the situation will be uncontrollable. I think the Chinese government should be critically aware of this.

SEVERSON: Even the most ardent followers of the Dalai Lama, like Arjia Rinpoche, appear to be losing hope that the Chinese government will come around.

Mr. RINPOCHE: When I escaped in 1998 then I thought, oh, in eight years I might return to home. Ten years, I’m pretty sure. So today is exactly the 10 years now. So the situation is getting worse.

SEVERSON: For now, there is little indication that the Chinese will relax control of Tibet. Many Tibetans are counting on the next and more informed generation of Chinese leaders to realize they are not a threat.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, I’m Lucky Severson reporting.