Bryan Stevenson: Equal Justice Initiative

BOB ABERNETHY: Now, the death penalty and one man’s fight to save convicted criminals from being executed. Thirty-eight states permit capital punishment, and polls show a majority of Americans favor it, but many people of faith are campaigning against the death penalty; among them, an African-American lawyer in Alabama. Lucky Severson begins our story at one of the country’s most famous Death Rows.

LUCKY SEVERSON: This is Death Row at San Quentin Prison in California. What is most striking about Death Row is the feeling of despair, the absolute want of hope or redemption. Many Americans believe that is as it should be. Bryan Stevenson does not. The Harvard-educated lawyer has dedicated his life to getting inmates, like Jesse Morrison, off Death Row.

Mr. BRYAN STEVENSON (Equal Justice Initiative): I have a vision that our criminal justice system ought to do better; that a system that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent doesn’t meet up to what an equal — a society committed to equal justice requires.

(To Man): Did the defense bring out that he had a deal for his testimony?

Did that come out to the jury?

SEVERSON: He draws only $27,000 a year from his nonprofit center here in Montgomery, Alabama. It’s called the Equal Justice Initiative, and it employs five other lawyers.

SEVERSON: He draws only $27,000 a year from his nonprofit center here in Montgomery, Alabama. It’s called the Equal Justice Initiative, and it employs five other lawyers.

Mr. STEVENSON: For me, it’s not about the appearance and the liturgy and the ritual of belief, it’s about the experience of belief. It’s about what faith compels you to do.

SEVERSON: On this day, he is testifying at a Senate hearing on two bills that would broaden the use of DNA evidence in criminal cases.

Mr. STEVENSON: As we sit here today, it’s very likely that there are innocent people awaiting execution.

Unidentified Woman: Each day, I think it was a different procedure, seemed like.

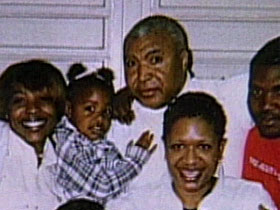

SEVERSON: Back in Alabama, he meets with the family of Robert Tarver, who became a client after he was convicted of shooting to death a grocery store owner during a robbery.

Mr. STEVENSON: I saw Robert after we got the stay of execution, and he told me how much your presence at the prison meant to him.

SEVERSON: But the Supreme Court decided not to hear Stevenson’s appeal, centered on the cruel nature of the electric chair, and Robert Tarver was executed April 14th of this year. These pictures were taken the day he was put to death. The family is grateful to Bryan Stevenson.

SEVERSON: But the Supreme Court decided not to hear Stevenson’s appeal, centered on the cruel nature of the electric chair, and Robert Tarver was executed April 14th of this year. These pictures were taken the day he was put to death. The family is grateful to Bryan Stevenson.

Unidentified Woman: And I just think he is just the most fantastic to care enough. It’s — I’m sorry.

Mr. STEVENSON: Growing up where I grew up, growing up how I grew up, I mean, I — we learned at an early age that justice is a constant struggle.

SEVERSON: He grew up in a small, segregated community in Delaware and struggled against racial prejudice, but what may have influenced Stevenson, who is now 40, more than anything was the faith he acquired in the African Methodist Church.

Mr. STEVENSON: I grew up in the church. I rely on a faith dynamic to get through every day. I believe things I haven’t seen. I operate on grace.

SEVERSON: The place he chose for his struggle is the same place George Wallace fought against equality and then championed it. Alabama has changed, but not as much as Bryan Stevenson would like. The state sentences more people to death per capita than any other state. Numerous studies have documented severe shortcomings for criminal defendants, such as no statewide public defender system and defense lawyers who are paid so little, they refuse to work.

Mr. STEVENSON: When we first came here, everybody said, “Well, why are you going to Alabama? That’s a terrible place to do this kind of work.” We needed to believe that we could get people released from Death Row after proving they’re innocent, even though we’d never seen that, and that’s what I mean by a faith dynamic.

Mr. STEVENSON: When we first came here, everybody said, “Well, why are you going to Alabama? That’s a terrible place to do this kind of work.” We needed to believe that we could get people released from Death Row after proving they’re innocent, even though we’d never seen that, and that’s what I mean by a faith dynamic.

SEVERSON: There are 185 inmates on Death Row in Alabama, men and women; half are black; some are probably not guilty as charged. In the last eight years, Bryan Stevenson and his colleagues have succeeded in reducing or overturning 67 death sentences.

One of those cases: George Daniel, now in a mental health facility after Stevenson presented evidence that the clinical psychologist who declared him competent was a fraud; and Willie Rusov — his sentence was reduced when Stevenson found that he was tried without a lawyer.

Mr. STEVENSON: Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done. I mean, I think if you tell a lie, you’re not just a liar. And if you take something that doesn’t belong to you, you’re not just a thief. Even if you kill somebody, you’re not just a killer. And so I think that there’s an obligation to defend the basic human dignity of every human being.

(At Congressional Hearing): I represented a man who spent six years on Death Row for a crime he didn’t commit, when he was actually placed on Death Row for 15 months before going to trial.

SEVERSON: This is Walter MacMillan, the man who spent six years on Death Row.

SEVERSON: This is Walter MacMillan, the man who spent six years on Death Row.

Mr. STEVENSON: Did they send you anything to sign?

SEVERSON: He was charged in 1987 with killing a young white woman. The trial lasted only a day and a half, and the main witness against him had a long criminal record.

Mr. STEVENSON: He was arrested and charged with that murder, even though at the time the crime took place, there was some 35 people in the community who could verify his whereabouts some 11 miles away. Most of those people, most of those alibi witnesses, were poor, were African American, and their testimony was simply ignored, discarded.

SEVERSON: The jury convicted Walter MacMillan, recommended a life sentence, but the judge sentenced him to death.

Mr. STEVENSON: To prevail, we had to confront a lot of animosity, a lot of ugliness. I mean, there were people who were absolutely furious about our involvement in that case, and we got personal threats, we got a lot of criticism.

SEVERSON: They got Walter MacMillan off Death Row and out of prison.

You feel bitter about this whole business?

Mr. WALTER MacMILLAN: I try to overlook it, but I — it’s come right back to me. You know, different — just remembering it at night, stuff like that. Just can’t forget it.

SEVERSON: Mariam Shehane can’t forget either the brutal rape and murder of her 21-year-old daughter Quenette in 1976. She has dedicated her life to a nonprofit organization called VOCAL, Victims of Crime and Leniency.

SEVERSON: Mariam Shehane can’t forget either the brutal rape and murder of her 21-year-old daughter Quenette in 1976. She has dedicated her life to a nonprofit organization called VOCAL, Victims of Crime and Leniency.

Ms. MARIAM SHEHANE (VOCAL): I very strongly believe in the death penalty because without it, you never are able to bury your loved one.

SEVERSON: Bryan Stevenson represented one of the three men convicted of the murder after he was put on Death Row. The man was ultimately executed.

What do you fault him with?

Ms. SHEHANE: That he just strictly does not believe in the death penalty, no matter what; that he takes on cases that he knows they’re guilty.

Mr. STEVENSON: A lot of my clients have committed crimes, and they have to be punished for that, and I don’t have any objection to that, but there are people for whom I believe redemption is still a possibility.

Ms. SHEHANE: I don’t know whether it’s redeeming or not. I just know it’s justice, and that it’s not revenge.

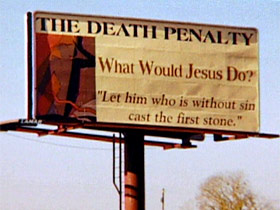

SEVERSON: Last November, Stevenson put up billboards in Montgomery asking the question, “What would Jesus do about capital punishment?”

Mr. STEVENSON: We felt it important that churches not hide from what is one of the critical, compelling moral issues of our day.

Mr. STEVENSON: We felt it important that churches not hide from what is one of the critical, compelling moral issues of our day.

SEVERSON: One billboard was right outside Reverend Joe Godfrey’s Baptist church.

How’d you react when you saw those billboards?

Reverend JOE GODFREY: I laughed to myself about the fact that whoever paid to put those billboards up really didn’t know what Jesus would do, because the Bible that I read very clearly allows for capital punishment.

SEVERSON: Reverend Godfrey says most everyone in his congregation supports capital punishment, and so does the Old Testament in Genesis, chapter 9, verse 6.

Rev. GODFREY: It says specifically, “Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man, his blood shall be shed, for in the image of God, he made man.”

Mr. STEVENSON: There’s a lot of support in the Bible for the notion that it is sometimes morally justified to take the life of another human being, and I just believe that we can do better than to kill people to show that killing is wrong.

SEVERSON: Bryan Stevenson faces an uphill battle. Alabama now has the fastest-growing Death Row in the country. I’m Lucky Severson for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly in Montgomery, Alabama.