In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

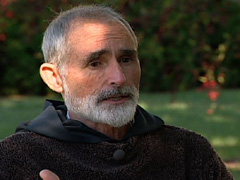

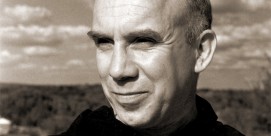

Brother Paul Quenon on Thomas Merton

Read more of Judy Valente’s interview about Thomas Merton with Brother Paul Quenon at Gethsemani Abbey:

Q: Describe for me what you think is the essence of the Trappist life.

A: Well, the essence of the Trappist life would be living in God, and I don’t think I would want to say much more than that. Of course, you’re living in God with other people in the same community, and it’s a life of continual prayer, and it’s a life of deepening, going deeper into your own capacity to love and to live with God.

Q: How would you describe the day of a Trappist, the spiritual discipline?

A: Well, the day of a Trappist is rather monotonous, but it’s full of activities. It’s monotonous in the sense that one day pretty much looks like another day. We get up at 3:00 in the morning and the first prayer is at 3:15. And then it’s still dark, you know, and it’s a nice, quiet time for reading until about 5:45 when we have Lauds, which is, you know, like a 25 minute prayer, choral prayer. Mass follows that and work begins at 8:00 in the morning. We work for four hours through, until 12:00. Then 12:15 is midday prayer, then lunch after that. We have the main meal in the middle of the day, and there’s a break until None, which is at 2:15, and then work in the afternoon or some, maybe, yard work or time to read, to do extra things. Vespers is 5:30 in the evening, supper after that, and then Compline at 7:30, and we go to bed at 8 o’clock. We still get seven hours of sleep.

Q: Did Thomas Merton influence your decision to come to the monastery?

A: Well, Merton did influence me. I read THE SEVEN STOREY MOUNTAIN when I was deliberating about entering a monastery. I’d already developed a thought reading THE IMITATION OF CHRIST, and then I could see that a modern man can do such a thing and that there actually is a monastery in the United States called Gethsemani Abbey. So I was, of course, filled with the images that he had in the book in anticipation about what the life could be.

Q: Tell me what he was like to live with.

A: Well, Merton – I call him Father Louis, because that was his religious name and that’s how I spoke to him – he was good humored, good natured, buoyant, and resilient. He was also pretty intense, because he was always working. If he wasn’t getting some course work ready, he was writing. And then when he did go to the lumber shed or to the woods to meditate, that’s what he was doing. He had a place where they use to split the logs for the wood furnace, the wood boiler, and he loved to go down there and sit on the hay bales and write his journal. He had this thick bookkeeper’s ledger book which served for his private journals, so when he was down there he was alone. He’d either meditate or fill out his ledger book.

Q: What can you tell us that might be surprising about him, or not so well known to those who read his books?

A: Well, he had false teeth. He actually had false teeth that he took out at night, so I’ve disclosed the worst about Thomas Merton. Actually, his health was not as good as you would expect, because he seemed vigorous. He had a lot of – he was on a special diet. He ate in the infirmary kitchen area, which was a kind of separate room from the monks’ refectory. They were served meat in that. That’s why it had to be separate, so the rest of us wouldn’t have our appetites whetted. I think probably he was a lot funnier than people expect when they’re reading his books. Father Louis had a quick wit. It’s not like he liked to tell jokes. He didn’t [tell] like formal jokes. He would just, on the spur of the moment, come up with something.

Q: Are there any vivid personal memories of him you can share?

A: Of course there are many just incidental things that I could think of. I’m thinking now of when we used to go out in a straight line to cut corn with machetes under our arms, all wearing the old blue denim work blouse and then the leggings, and he would be at the head of the line of novices with his straw hat on, and he had a way of walking which, to me, reflected the way a sheaf of corn flops to the side, and he kind of had like a farmer’s strut about him. He obviously enjoyed what he was doing in going out with us.

Q: How did he affect your own spiritual journey?

A: When I used to have spiritual direction with Father Louis, which would be about once every two weeks, one of the moments that comes back to me from time to time is when we were talking about prayer and that prayer is like a struggle with God. It’s like Jacob struggling with the angel in the night, and when you’re encountering God God is not a thing, and so God is more like nothing, so when you enter into the depth of prayer it’s like entering into nothingness. And of course, that’s very central to his whole spirituality.

Q: What was the core of his spirituality?

A: Well, hopefully God was the core of Merton’s spirituality; I think the quest for God in solitude and this coming to the innermost core of your self. You know, he says contemplation is an answer to a call, a call from one who has no voice but who speaks in everything that is, and most of all in the depths of our own being. And so for him there was a mystery about the self, which was like the mystery of God, and they’re just really all one mystery as far as we are concerned. It’s in the process of coming to knowledge of yourself that you come to knowledge of God, or even truer to say that in coming to knowledge of God in a direct way is the only place you come to knowledge of yourself. We are a mystery unto ourselves, and God is a mystery, and the two mysteries merge, and to accept that kind of helplessness, the human mind is helpless in the face of all this. To accept that kind of poverty and emptiness would be the whole atmosphere of Merton’s spirituality.

Q: Why do so many successive generations continue to find his writing so compelling?

A: Well, Merton was a very sincere person. He, you know, was eloquent, but his eloquence came from a kind of directness and honesty about what he’s experiencing. I mean, he was a very sophisticated writer. But he had to learn how to live with himself. He was very quick to say things, but he was also somebody who spoke with a lot of sincerity, and that’s human. That appeals to people.

Q: Why do people not in monastic life respond so positively to what he wrote?

A: That’s still a mystery to me. I think he started out with [the idea] that he would be writing little book reviews in the back of some obscure journal and had no idea that he was going to become a famous writer. Merton was very human, so that, immediately, is one appeal. The other is that he consciously approaches it. He writes for monks, certainly. I mean that’s at the core, and his best writing is for monks about monastic topics, but he was a cosmopolitan, so he always had a broader audience in view. And he is not sectarian. I mean, he’s radically a Christian, but I think he keeps the broader perspective in mind, and he doesn’t think the whole world are monks. But on the other hand, he can talk to the monk in each person. He sees it as a deep enough thing that somehow everybody has the capacity to come to that same kind of intensity and depth of experience of God. And he was convinced, you know, we’re all called to experience God, if not in this life certainly in the next, but hopefully in this life, and so he spoke to awaken that in people.

Q: What do you think he came to this monastery seeking?

A: Well, Merton came to the Abbey at Gethsemani because he perceived it as dedicated to the contemplative life, a simple life, monks who lived in poverty and in silence. I’m not sure he was even aware that there were other such monasteries in the United States at the time. He always had a kind of a dream of that since he was a child, when he would look through these picture books of medieval monasteries in Europe, and some kind of a dream was awakened in him. And he came down here to make a retreat and discovered, just by immediate contact, what the place was – men who are just totally dedicated to the life of prayer, and their whole life is centered around that. That was somehow a dream reawakened.

Q: Is there anything else you want to add about Merton or the monastery?

A: Well, it has been forty years since Father Louis died. We’ve come a long way since then, and a lot of it has been under the impetus that he had, the waves that he made. And I think it’s been a good, for the most part it’s been a good effect. We certainly have a more, a broader perspective on life. I think we have become so popular we’re almost too popular nowadays, and so we’re reevaluating what are the radical qualities of the Cistercian life, and Merton has been somebody who has given us a voice about that. And so he continues to speak to monks and at the same time continues to be a challenge to monks. We have a better appreciation of the variety of vocations within the monastic life. We have developed an appreciation for the solitary life of a hermit, and we have a better appreciation of the intellectual challenges that are present to us in the monastic life which were not considered something a monk would aspire to, but the fact of the matter is that Merton was an example of what can be done within the context of monastic life.

Q: And his interest in Eastern religions is an example as well?

A: Yes, I think we have found a kinship with Buddhist monks. They come here in small groups, and I’ll be meeting with [one] tomorrow, and perhaps at the beginning of November another small group will be coming. Matthieu Ricard came in the spring. He’s been associated with the Dalai Lama for 17 years at least. So there’s a kind of universality that we appreciate more now than we ever did before.