DNA and Fair Trials

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: More than 20 years ago, in Arizona, a man accused of raping a child was tried, convicted, and sent to prison. The evidence was overwhelming. But, in fact, justice was not done, raising the question: in the matter of a serious crime, when someone is given a long prison sentence, should it ever be too late to reopen the case?

Tim O’Brien covered the story for ABC NEWS in 1988. But the story was far from over. Now, drawing on the ABC NEWS archives, he takes another look.

TIM O’BRIEN: Larry Youngblood had been charged with a horrible crime. Police said in 1983, he abducted a 10-year-old boy, holding him captive for three days — repeatedly raping and sodomizing the child.

Youngblood seemed to match an artist’s conception provided by the victim: a black man, medium build, with one bad eye. The little boy later picked Youngblood from pictures of six black men, each of whom had one eye blotted out. And he identified Youngblood again in court as the rapist.

DEBORAH WARD (Former Prosecutor) (From ABC NEWS Interview): We certainly had enough evidence to meet our burden, beyond a reasonable doubt. The youngster identified the vehicle that the man had as a medium-sized, white vehicle with a junky inside, with a torn blanket in it.

O’BRIEN: Youngblood insisted police had the wrong man.

LARRY YOUNGBLOOD (From ABC NEWS Interview): Sure, I have one eye. Yeah, but, you know, must I be punished for a crime that was committed because the fact that I have a bad eye?

O’BRIEN: The jury didn’t believe him, quickly convicting Youngblood on rape charges.

Mr. YOUNGBLOOD (From ABC NEWS Interview): They went out and in 45 minutes came back and said that I was guilty.

O’BRIEN: On appeal, Youngblood’s lawyers argued that had police only preserved semen samples from the victim’s clothing — refrigerating them. They could have performed blood tests that would have proved they had the wrong man.

The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, leading to a landmark ruling in 1988 that police have no constitutional obligation to preserve evidence. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote separately to say the case against Youngblood appeared so strong, the failure of police to preserve evidence in his case was “immaterial.”

Whether police have any constitutional obligation to preserve evidence was a significant question. When I first covered this story for ABC NEWS 18 years ago, I must confess I questioned why the defense would bring such an important issue to the Supreme Court with a client who seemed so guilty.

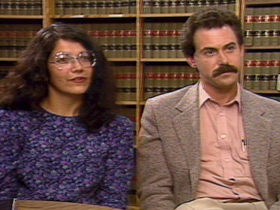

(To Dan Davis and Carol Wittels) (From ABC NEWS Interview): You both are absolutely convinced, beyond a reasonable doubt, as they say, that your client is innocent?

DAN DAVIS (Defense Attorney) (From ABC NEWS Interview): Beyond any doubt.

CAROL WITTELS (Defense Attorney) (From ABC NEWS Interview): I’m convinced beyond any doubt whatsoever.

O’BRIEN: The Supreme Court ruling sent Youngblood on his way to a 10-year prison term. He finally got out in 1999, but then he failed to register as a convicted sex offender, as Arizona law requires.

Mr. YOUNGBLOOD: I just told them I forgot, that’s all.

O’BRIEN: He was re-arrested and sent back to jail. Youngblood’s former lawyer, Carol Wittels, again agreed to help him. Only this time, there would be a significant difference. New tests on the victim’s clothing — DNA tests not available at the time of the trial — allowed Wittels one more chance to prove that Youngblood, who had already served nearly 10 years in prison, was innocent.

Tucson police agreed to conduct the tests themselves in their crime lab. John Leavitt, the patrolman first assigned to the case in 1983 and now an assistant chief of police, believed the tests would only confirm Youngblood’s guilt.

O’BRIEN: It must have seemed like an airtight case.

JOHN LEAVITT (Assistant Chief of Police, Pima County): It seemed like a slam dunk.

O’BRIEN: Then came the shocker. The DNA tests proved conclusively Youngblood was innocent — that it really was, as he and his lawyers had claimed all along, a case of mistaken identity.

No sex offender, Youngblood was immediately released from jail.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN (To Mr. Youngblood as He Leaves the Prison): Welcome home, man, it’s been too long, too long.

UNIDENTIFIED REPORTER (To Mr. Youngblood): Well, how’s it feel to walk out of here?

Mr. YOUNGBLOOD: It feels wonderful to walk out here, because it was so hectic in there — but now I can breathe that fresh air.

Ms. WITTELS: I was very happy. I was not one bit surprised.

O’BRIEN: Youngblood’s lawyer says she’ll never forget the look on prosecutors’ faces when they told her of the test results.

Ms. WITTELS: They looked like somebody had died. They were very serious when they told me that Larry had been cleared. And I was ecstatic.

O’BRIEN: The lead prosecutor, Deborah Ward, is now a superior court judge.

Judge WARD (Pima County, Arizona Superior Court): Well, I was pretty shocked.

O’BRIEN (To Judge Ward): Is Youngblood owed an apology?

Judge WARD: You know, that’s really hard for me to answer. I suppose on one level, certainly.

O’BRIEN: The DNA test results from the victim’s clothing were later placed in a FBI data bank, leading to the arrest and conviction of Walter Cruise, who pleaded guilty four years ago and is now serving a 24-year prison term.

The Constitution only requires a fair trial, not a perfect trial. And even the fairest of trials cannot assure that the wrong person won’t be convicted, or that the right person will. This remarkable case, however, could become a catalyst for reforms, to at least make it less likely that what happened to Larry Youngblood will happen again.

The American Judicature Society, a private organization devoted to improving the court system, is leading the way. Its former president, Larry Hammond, lectures widely on the Youngblood case and holds seminars on its lessons.

LARRY HAMMOND (Former President, American Judicature Society): We must have a system that preserves evidence and that makes it available for inspection and that opens the courthouse door to the consideration of that evidence.

O’BRIEN (To Mr. Hammond): At any time?

Mr. HAMMOND: At any time. No scientist would disagree with that. No one who cares about getting it right would disagree with that.

O’BRIEN: Yet, citing the need for finality, the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld state laws that sharply limit any right to open up old convictions — even in death penalty cases.

Had Youngblood been charged with a capital offense, he might have been executed.

Mr. YOUNGBLOOD: If they destroy the evidence, you don’t have a chance. You could die. And then years later, somebody says, “Well, you know what? Here it is. We found this piece of evidence. And that guy we killed three years ago wasn’t even the guy.” That’s kind of horrible.

O’BRIEN: The Youngblood case also shows that prosecutors, judges, and juries should be skeptical of eyewitness testimony, especially when children are involved; especially when the victim and the perpetrator are of different races, as they were in this case.

Mr. HAMMOND: I’ve shown the photographs of Walter Cruise and Larry Youngblood to many audiences now and it’s one of the most interesting experiments that I’ve been engaged in in my career as a lawyer. If you show those two photographs to a white audience, the immediate reaction is, “They look a lot alike.” If you show those same two pictures to a black audience, people say, “They don’t look alike at all.”

O’BRIEN: Hammond says reforms are not likely to come from the Supreme Court, but rather from the ground up, from individual prosecutors and police departments around the country.

Defense attorney Carol Wittels insists simple justice should require states to set up “innocence commissions” to reexamine old convictions and that there should be no bar to opening up old cases when persuasive new evidence is uncovered.

Ms. WITTELS: What good is finality if you don’t have the right answer?

O’BRIEN: And, says Wittels, simple fairness requires compensation boards be established to compensate inmates like Larry Youngblood who have been wrongly imprisoned.

Youngblood himself is trying to rebuild his life. He has yet to receive any compensation for the 10 years he spent in prison — yet to receive any formal apology.

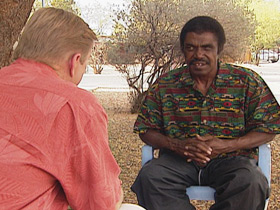

O’BRIEN (To Mr. Youngblood): What did they say to you?

Mr. YOUNGBLOOD: They didn’t say anything. I never got an apology — I never got nothing from any one of them.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Tim O’Brien in Tucson, Arizona.