Easter Reconciliation in Northern Ireland

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Holy Week and Easter have special significance in Northern Ireland, a land torn by decades of religious conflict. It was on Good Friday in 1998 that Catholics and Protestants negotiated a power-sharing agreement designed to end hostilities. Seven years after the Good Friday accords, violence has decreased substantially, but lasting peace still has not come. Amid the ongoing tensions, a Benedictine monastery is working for reconciliation and unity. Kim Lawton has our profile of the monks and their work.

KIM LAWTON: Early spring in the foothills of the Mourne Mountains south of Belfast. Signs of new life are at every turn. This tranquil setting seems far removed from the Troubles, as people here call the hatred and killing that have wracked Northern Ireland for decades.

But Father Mark-Ephrem Nolan, abbot of Holy Cross Benedictine Monastery in Rostrevor, says bitterness here still runs deep.

Father MARK-EPHREM NOLAN (Abbot, Holy Cross Benedictine Monastery, Rostrevor, Ireland): There has been so much pain and suffering. I think it is sometimes very hard for people from outside this country to measure to what extent people’s lives have been deeply, deeply affected by the Troubles.

LAWTON: The very modern Holy Cross Monastery was dedicated just over a year ago, the first Benedictine monastery in Northern Ireland since the year 1183. It was established to work for peace and reconciliation.

Father NOLAN: Quite often, we talk of the two communities in Northern Ireland. I don’t think we can think of two communities in Christian terms. Perhaps you have got two political communities. There is one Christian community, which is divided within itself, and our call is to be reconciled in Christ Jesus.

LAWTON: The monastery is run by Nolan and four other monks who came with him from France in 1998. They were inspired by a Vatican document that urged monks and nuns to take their contemplative lives of prayer out into corners of the globe where people are divided. Nolan was born in Belfast and felt a call to minister in his conflict-ridden homeland. His French brother-monks shared his vision.

Father NOLAN: We hope to live here, and I think that’s at the heart of the monastic vocation — a ministry of compassion, to be with people who have suffered, who are suffering, to be a sign of the presence of Christ.

LAWTON: They live by the Rule of Saint Benedict, the set of instructions written in the sixth century by the founder of Western monasticism. It’s a simple life, marked by manual work, Bible study, regular intervals of prayer, and long periods of silence. The monks at Holy Cross support themselves by making candles, which are sold around the world. They also practice hospitality, with a guesthouse where people can come for spiritual retreat.

The monks gather five times daily to pray. People from all denominations in the community are invited to join them. Every day they pray for national healing, for peace and unity, and every day they pray for Catholic and Protestant church leaders by name.

Father NOLAN: A psychiatrist came one morning, a Catholic layman. He said to me, “You have no idea the bombshell you drop when you name the Presbyterian minister and the elders in the congregation.” He said, “People just have never heard that before.”

LAWTON: The monastery sponsors public healing services, where Catholics and Protestants alike talk openly about their stories of pain and loss. Holy Cross also hosts regular dialogue sessions for local Catholic and Protestant clergy.

Participants, including this Protestant pastor, say they’ve been touched.

UNIDENTIFIED PROTESTANT CLERGYMAN (At Service): I have experienced this community to be a community that holds a safe space, where the grace of God’s forgiveness and God’s work of reconciliation can flow.

LAWTON: The monks’ impact is being felt well beyond the community. One big supporter is the former Archbishop of Canterbury, the Anglican George Carey, who spoke at the monastery’s ecumenical dedication ceremony in January 2004.

Lord GEORGE CAREY (Former Archbishop of Canterbury): This monastery is a sign of hope that together we can do something, and we can do far more.

LAWTON: The monks have also gained an international following thanks to brisk sales of their CD of Gregorian and Taize chants.

But Father Nolan believes their biggest impact is in simply trying to live what they preach. He calls it “truthful living.”

Father NOLAN: The fact that we are trying to live reconciliation with our brothers day after day, brothers whom we didn’t choose, brothers whose legitimate differences we have to recognize and accept and rejoice in — then that speaks to the churches.

LAWTON: Here at Holy Cross, Nolan says the themes of Holy Week and Easter resonate deeply. Above their altar is an icon of Jesus on the cross. The inscription at the top reads, “May All Be One,” taken from Jesus’ prayer on the eve of his crucifixion — a constant reminder, Nolan says, that hope can come out of death.

Father NOLAN: We are, there’s no doubt, a marked people, a scarred people, a wounded people. But I think, by the power of God’s grace, those wounds can, in fact, become signs of resurrection and new life.

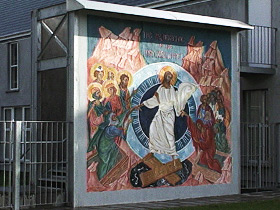

LAWTON: At the entrance of the monastery stands a giant version of the traditional resurrection icon. They have a smaller version inside, as well. Nolan says he loves the symbolism, which conveys the very core of his faith.

Father NOLAN: Christ, who is depicted here as trampling underfoot death and the powers of the underworld, pulling Adam and Eve, man and woman, forth from the regions of darkness, the regions of death — forth from the tomb, literally. Christ has a strong grasp there on Adam, pulling him forth, and there’s a gentle bidding of Eve.

LAWTON: They placed the icon at the entrance in order to proclaim their belief that the risen Jesus is in their midst.

Father NOLAN: That’s what we want to share with those who come to the monastery — that life of the risen Lord who is the one who brings us forth from darkness and brings us forth from the shadow of death, who gives new hope to people who have suffered and who is there with his message of peace.

LAWTON: It’s an Easter message, the monks say, for all year long.

I’m Kim Lawton in Rostrevor, Northern Ireland.

LAWTON (August 5, 2005): I was in touch with Father Nolan again this week. He told me his community feels great joy at the IRA disarmament, but they also know that hopes have come and gone many times before. He said, “It is clear that a long, long process of healing has to be lived through in our deeply wounded and still so bitterly divided society.” [Read Father Mark-Ephrem Nolan’s comments on the Irish Republican Army’s July 28, 2005 statement ending its armed struggle.]