Juvenile Death Penalty Update

KIM LAWTON, guest anchor: Also this week, in a 5-to-4 decision, the high court ruled that executing people for crimes they committed before the age of 18 is unconstitutional. This means that the dozens of people on death row for crimes committed as juveniles will now have a sentence of life in prison. The case that brought the issue to the Supreme Court involved a young Missouri man named Chris Simmons. Tim O’Brien has the story.

TIM O’BRIEN: It started as a burglary at this home in Fenton, Missouri — about 30 miles south of St. Louis — early on a September morning in 1993. It turned into a gruesome murder.

ED KEMP (Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department): While in the home, the victim woke up, recognized both subjects. They bound her, put her in her own vehicle, transported her to a bridge and threw her over — alive.

O’BRIEN: Acting on an informant’s tip, police arrested two young suspects. Fifteen-year old Charlie Benjamin and 17-year-old Chris Simmons were picked up at their high school a day after the murder. After first denying any involvement, Simmons later gave a tearful confession to police:

CHRIS SIMMONS (confessing on tape): I had her tied up. She walked out on the bridge and I tied her hands and feet together and pushed her off.

UNIDENTIFIED POLICEMAN #1: Who pushed her?

Mr. SIMMONS: I did.

UNIDENTIFIED POLICEMAN #1: Who?

Mr. SIMMONS: I did.

UNIDENTIFIED POLICEMAN #1: You pushed her?

Mr. SIMMONS: I did.

UNIDENTIFIED POLICEMAN #1: Okay, Chris.

O’BRIEN: Simmons even reenacted the crime for police.

UNIDENTIFIED POLICEMAN #2 (on police video): So this about where you threw her off?

Mr. SIMMONS (gesturing): Yeah.

O’BRIEN: Simmons’s lawyer tried to get him to accept a deal — life in prison in exchange for a guilty plea. But Simmons wouldn’t hear of it.

DAVID CROSBY (Defense Attorney): We were set for a course that eventually led to trial. Here’s a child that in Missouri couldn’t buy a car because he’s under age to contract, and yet he makes life-and-death decisions.

O’BRIEN: It was an open-and-shut case.

JURY FOREMAN (at trial): We the jury find the defendant Christopher Simmons guilty of murder in the first degree.

O’BRIEN: The younger boy was sentenced to life with no parole. Simmons, 17, got the death penalty.

But a little over a year ago, the Missouri Supreme Court set aside Simmons’s death sentence, reducing it to life in prison with no parole. The court held it violates this country’s evolving standards of decency to execute anyone who was under 18 at the time of the crime — that it may have been permissible in the past, but that now it conflicts with the Eighth Amendment guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment.

This week, a bitterly divided U.S. Supreme Court agreed.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, for a five-justice majority, observed that not only do 30 states now reject the death penalty for juveniles but that “it is fair to say that the United States now stands alone in a world that has turned its face against the juvenile death penalty.”

In a friend of the court brief, 18 recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize had urged the court to rule as it did, including former Presidents Jimmy Carter, Mikhail Gorbachev and Lech Walesa — also South Africa’s Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama. They told the court that “the death penalty for child offenders is contrary to internationally accepted standards of human rights.”

Sixteen years ago, the court had squarely rejected that argument in a decision that Justice Kennedy joined. Kennedy’s change of heart provided the crucial fifth vote to change course.

Justice Antonin Scalia penned an angry dissent, dismissing the court’s majority opinion as nothing more than “the subjective views of five members of this court and like-minded foreigners.” Scalia, joined by Justices Thomas and the ailing Chief Justice William Rehnquist, said the views of the international community should have no bearing on what the U.S. Constitution means.

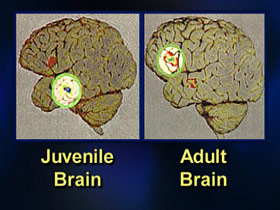

The court also appeared to rely heavily on claims that juveniles are ordinarily not as culpable as adults who may commit similar crimes. The American Psychiatric Association told the court that magnetic resonance imaging — MRIs like this — show that juveniles use a different part of the brain in the decision-making process than adults, making them more likely to act irrationally, less likely to appreciate the consequences of what they do.

Dr. RICHARD RATNER (American Psychiatric Association): We have learned a lot more about the function and the structure and the development of the brain.

O’BRIEN: Dr. Ratner says not only has the execution of juvenile offenders become less acceptable but new research suggests the court also got it wrong back in 1989 when it first authorized the death penalty for juveniles.

Dr. RATNER: And in a nutshell, it is that the brain has not really matured; you do not really have an adult brain until you are in your early 20s.

O’BRIEN: You have actual empirical evidence?

Dr. RATNER: Yes, we do.

O’BRIEN: Did the Supreme Court get it right? Not if you ask Pertie Mitchell, the sister of the woman Chris Simmons murdered.

PERTIE MITCHELL (Victim’s Sister): And you know what they said? These boys went to school the next day, and they were bragging about what they had done. They said, “Guess what we did last night? We beat up an old lady, and we took her out to the trestle, and we pushed her off, and guess what she did? She went ‘bubble, bubble.'” You think that didn’t hurt us!

O’BRIEN: Who could do such a terrible thing? While prosecutors say the victim could have been anyone, Chris Simmons’s mother says the perpetrator could have been anyone’s son.

SHERYL HAYES (Defendant’s Mother): We were caring parents for him. We did everything we could. We probably spoiled him. But there were things he was doing I had no idea he was doing. It’s broken my heart. You think about it every day. A lot of my thought is if I could just turn time backwards and none of this had ever happened.

O’BRIEN: The case of Lee Malvo had galvanized public opinion on the execution of juvenile offenders. Malvo was convicted of participating in a random sniper spree that left 10 people dead in the Washington, D.C. area two years ago. Despite his youth, prosecutors in Virginia were poised to seek the death penalty for Malvo, had the Supreme Court allowed it. He will now be spared, as will Chris Simmons and more than 70 other death row inmates who were under 18 at the time of their crimes. As a result of the High Court’s ruling, they may not be executed. Their sentences will all be reduced to life in prison.

For RELIGION & ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, I’m Tim O’Brien in Washington.