In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Christianity’s Lost History

BOOK REVIEW

Recovering a Forgotten Chapter

by J. Peter Pham

Nowadays, any serious discussion of the shifting demographics of Christianity inevitably leads to Philip Jenkins, the Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of the Humanities in History and Religious Studies at Penn State University.

With the monumental trilogy he completed two years ago—The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity (2002, revised 2007), The New Faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the Global South (2006), and God’s Continent: Christianity, Islam, and Europe’s Religious Crisis (2007)—Jenkins transformed perceptions of Christianity in the world today with the convincing case he made that not only has the center of gravity in the Christian world “shifted inexorably southward, to Africa and Latin America,” but much of conventional wisdom about religion in Europe (and, ultimately, North America) needs to be reconsidered. In the course of developing his argument about the present and future, Jenkins also hinted that the dynamics driving the changes were not entirely new, and the church’s past contained more than its share of surprises.

Thus, like its predecessors, Jenkins’s most recent book, The Lost History of Christianity (HarperOne, 2008) challenges what most of its readers thought they knew, in this case, about the faith’s historical itinerary. The volume’s subtitle, “The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia—and How It Died,” points to its author’s aim of recovering for today’s globalized world a more inclusive vision than the tendency of “thinking of Christianity as traditionally based in Europe and North America.” In contrast to that limited perspective, Jenkins argues:

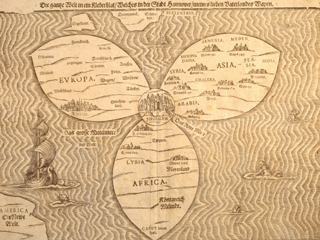

The particular shape of Christianity with which we are familiar is a radical departure from what was for well over a millennium the historical norm: another, earlier global Christianity once existed. For most of its history, Christianity was a tricontinental religion, with powerful representation in Europe, Africa, and Asia, and this was true into the fourteenth century. Christianity became predominantly European not because this continent had any obvious affinity for that faith, but by default: Europe was the continent where it was not destroyed. Matters could have easily developed differently.

While Christianity was born in the Levant, today its history is largely thought of in terms the two great centers, both in Europe, around which the ecclesiastical politics within the Roman Empire coalesced—Rome and Constantinople. What gets forgotten is that there were other great centers beyond the frontiers of the oikoumene and that much of what is now referred to as “the Islamic world” was once Christian.

To illustrate his point, Jenkins focuses on the figure of Timothy I (727-823) who, in 780, was enthroned as patriarch, or catholicos, of the Church of the East, then based in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Seleucia, less than two dozen miles southeast of modern Baghdad. According to Jenkins, “in terms of his prestige, and the geographical extent of his authority, Timothy was arguably the most significant Christian spiritual leader of his day, much more influential than the Western pope, in Rome, and on par with the Orthodox patriarch in Constantinople,” since “perhaps a quarter of the world’s Christians looked to Timothy as both spiritual and political head.”

While the medieval English church, for example, had only two metropolitans, the archbishops of Canterbury and York, Timothy presided over no fewer than 19 metropolitans and 85 other diocesan bishops. During his more than four-decade-long patriarchate, Timothy created no fewer than five new metropolitan sees, including one at Rai, near modern-day Tehran, and erected a diocese in Yemen alongside the four on the Arabian Peninsula that he had inherited from his predecessor. In a letter quoted by Jenkins, the patriarch boasted about how, after the conversion of the Turkish great king who ruled over much of central Asia, the khagan, “the Holy Spirit has anointed a metropolitan for the Turks.” This outward expansion was not unprecedented: missionaries from the Church of the East, whose adherents had been branded heretical Nestorians by the Council of Ephesus (431) and were largely driven out the Roman Empire, had roamed as far as China and Tibet and succeeded in establishing bishoprics in those parts by around 600.

As Jenkins points out, the Nestorians, along with the Egyptian (Coptic) and Syrian (Jacobite) Christians, who were anathematized as Monophysites by Rome and Constantinople following the Council of Chalcedon (451), not only constituted “the Christian mainstream in large portions of the world” but also “possessed a vibrant lineal and cultural connection to the earliest Jesus movement of Syria and Palestine,” being rooted in the Semitic languages of the Middle East with faithful who still thought and spoke in Syriac. Even after the Arab conquests, these believers retained such vibrant culture that “in terms of the number and splendor of its churches and monasteries, its vast scholarship and dazzling spirituality, Iraq,” for example, “was through the late Middle Ages at least as much a cultural and spiritual heartland of Christianity as was France or Germany, or indeed Ireland.” Nor were these Eastern Christians turned inward. Rather, together with Jewish sages, they dominated the cultural and intellectual life of what was to become the “Muslim world.” Jenkins notes:

It was Christians—Nestorians, Jacobite, Orthodox, and others—who preserved and translated the cultural inheritance of the ancient world—the science, philosophy, and medicine—and who transmitted it to centers like Baghdad and Damascus. Much of what we call Arab scholarship was in reality Syriac, Persian, and Coptic, and it was not necessarily Muslim. Syriac-speaking Christian scholars brought the works of Aristotle to the Muslim world: Timothy himself translated Aristotle’s Topics from Syriac into Arabic, at the behest of the caliph. Syriac Christians even make the first reference to the efficient Indian numbering system that we know today as “Arabic,” and long before this technique gained currency among Muslim thinkers…Such were the Christian roots of the Arabic golden age.

While the Arab Muslim conquests of the seventh century subjected the Christians of the Middle East to incredible pressures, the ancient communities nonetheless not only survived, as underscored by the remarkable renaissance of the Church of the East during the patriarchate of Timothy I, but even managed to thrive. “Only around 1300,” writes Jenkins, “did the axe fall, and quite suddenly.” The factors for this tragic turn of events, he argues, were global:

The aftereffects of the Mongol invasions certainly played their part, by terrifying Muslims and others with the prospect of a direct threat to their social and religious power. Climatic factors were also critical, as the world entered a period of rapid cooling, precipitating bad harvests and shrinking trade routes: a frightened and impoverished world looks for scapegoats.

Thus “Muslim regimes and mobs now delivered near-fatal blows to weakened Christian churches.” According to Jenkins, the number of Christians in Asia fell, between 1200 and 1500, from 21 million to 3.4 million. During the same years, the proportion of the world’s total Christian population living in Africa and Asia combined fell from 34 percent to just 6 percent, and the remnant that survived virtually disappeared in the massacres of Armenians, Assyrians, Syrians, and other ancient Christian communities during the 19th and 20th centuries, which led the Polish Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin argue for a new category of crime to which he subsequently gave the name “genocide.”

Had the author been satisfied with merely rendering accessible to a broader audience this fascinating, but little known, story, The Lost History of Christianity would nonetheless already constitute an invaluable contribution to our knowledge of the Middle East and Africa. For Jenkins, however, the historical narrative he assembled is but the foundation on which to pose several questions of considerable contemporary relevance.

Shifting focus from Mesopotamia to Africa, Jenkins considers the very different fates of the church in Egypt and elsewhere in North Africa. In the sixth century, there were more than 500 bishops, successors of church fathers such as Cyprian of Carthage and Augustine of Hippo, ministering in what today are Libya, Algeria, and Tunisia; barely two centuries later not one was left, their churches having vanished in the face of the Muslim invasion.

In contrast, in Egypt, which was conquered by the armies of ‘Amr ibn al-‘As in 640, not only did the Coptic church survive, but it continues, even today, to be the faith of at least 10 percent of the population. After discounting a number of explanations, Jenkins concludes that the key factor is “how deep a church planted its roots in a particular community, and how far the religion became part of the air that ordinary people breathed.” Whereas the Latin church of North Africa was essentially a colonial faith, appealing mainly to urban elites, the Coptic clergy translated their doctrine and practices into the idioms readily grasped by ordinary people, both city dwellers and rural peasants. Thus, despite persecutions, the Copts survived and their patriarchate spread Christianity up the Nile, deep into Africa to Nubia in present-day northern Sudan, which remained a Christian kingdom into the 15th century, and to Ethiopia (which also had contact with Syriac Christians), where the local church remains in communion with the see of Alexandria to this day. The lesson Jenkins draws here—although some might well be discomfited by the terms with which he articulates it—is that “for churches as for businesses, failure often results from a lack of diversification, from attaching one’s fortunes too closely to one particular set of circumstances, political or social.”

Jenkins also uses the chronicle of the long endurance of ancient Christian communities in areas which came under Muslim rule to inquire just how far churches, which he asserts must adapt when faced with “a powerful and hostile hegemonic culture,” can take accommodation:

Historically, Christians faced the issue of whether to speak and think in the language of their anti-Christian rulers. If they refused to accommodate, they were accepting utter marginality…Yet accepting the dominant language and culture accelerated the already strong tendency to assimilate to the ruling culture, even if the process took generations. Although a comparable linguistic gulf does not separate modern Western churches from the secular world, Christians still face the dilemma of speaking the languages of power, of presenting their ideas in the conceptual framework of modern physics and biology, of social and behavioral science. To take one example, when churches view sin as dysfunction, an issue for therapy rather than prayer, Christians are indeed able to participate in national discourse, but they do not necessarily have anything to offer that is distinctive…Too little adaption means irrelevance; too much leads to assimilation and, often, disappearance.

Since so much of the story that Jenkins reconstructs is centered in historical Mesopotamia, it is fitting that he draws his account together with several vignettes from contemporary Iraq. As recently as the 1970s, Christians made up five or six percent of that country’s population. That number is now barely one percent, and it is declining rapidly. Even as late as the onset of the first Gulf War, Christians made up as much as one-fifth of Iraq’s teachers and other professional groups. The devastation of the economy under international sanctions, however, pushed many to leave, and the Islamist militants unleashed in the wake of the collapse of Saddam Hussein’s regime quickly turn on those still left in the country.

Jenkins relates the tale of one of the most active priests in Mosul, Father Ragheed Ganni of the Chaldean Catholic Church, a body that, although in communion with Rome, actually traces its origins to the Nestorians of the Church of the East. Father Ragheed was known for the many messages he sent out abroad about of his desperate co-religious: “Priests celebrate mass amidst bombed out ruins; mothers worry as they see their children face danger to attend catechism…the elderly come to entrust their fleeing families to God’s protection.” On Trinity Sunday 2007, the priest and three subdeacons were kidnapped and killed, their bodies booby-trapped to make recovery even more difficult. Less than a year later, just days before the beginning of Holy Week 2008, the slain Father Ragheed’s own bishop, Archbishop Mar Paulos Faraj Rahhos, was kidnapped and then murdered by Islamists who demanded that his parishioners pay the jizya, the Islamic poll tax on non-Muslims. Not surprisingly, since the United States-led invasion in 2003, two-thirds of Iraq’s remaining Christians have fled abroad.

But Jenkins manages to preserve a small sliver of optimism, pointing out that while thousands of Christians from the Middle East have gone into exile, the story of their churches continues outside the region. In recent years, ancient Syrian Orthodox (Jacobite) orders have founded monasteries in the Netherlands and Switzerland. Timothy’s distant successor Catholicos-Patriarch of the Church of the East, Mar Dinkha IV, makes his home in Chicago, from where he oversees new sees in North America, Europe, and Australia which have taken the place of the historic bishoprics in places like Basra, Kirkuk, and Tikrit (the hometown of Saddam Hussein), which no one conceives of as the Christian strongholds they once were. Jenkins observes that, in the West, “members of these ancient communities are annoyed to be asked just when they converted to Christianity,” having to explain patiently that “their Christian heritage goes back a good deal further than that of their new host countries.”

Jenkins’s well-crafted new volume, filled as one has come to expect from the author with a good number of provocative insights, is not only a welcome addition to the literature on Christianity as a truly global religion, to which he has already made substantial contributions, but also an invitation to retrieve a forgotten chapter of history that has not inconsiderable relevance to current events. Recovering the memory of that “lost world,” with all its experience and wisdom, might lead to a better appreciation in our own age of the changing realities of a faith that is both ever ancient and ever new.

J. Peter Pham, director of the Nelson Institute for International and Public Affairs at James Madison University in Virginia, is the author of numerous works on religion, international affairs, and African politics. An ordained priest of the Episcopal Diocese of Quincy, he also serves on the advisory board of Save Iraqi Christians. He last wrote for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly on the Anglican Communion.