In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Homage and Commemoration

by Lorrie Goldensohn

In A FAREWELL TO ARMS, Ernest Hemingway famously wrote about the dim possibility of adequate commemoration for those lost in the slaughter of World War I:

“I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it. There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the number of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.”

When Hemingway wrote, war poetry was still poised between the old and durable need to honor the dead and acknowledge with both regret and proper gratitude the dire nature of their civic contribution, and the second and more unsettling need to voice the sometimes dishonored and dishonoring terms of that sacrifice — the anguished appearance of war guilt for crimes perpetrated during the course of war by some of these sacrificial victims, the soldiers.

By the second half of the last century, war poetry came to embody an antiwar ideology. Judgments about politics and history have thoroughly rearranged the conventions of the war poem and have changed the way we look at courage and honor, as well as sacrifice. Part of what has happened is also an awareness of the bastardizing of public language, although I shrink from any judgment that things are any worse now for words than they ever were. It has never been easy to speak well about the moving target of difficult issues like war. There are certainly always new problems and new situations, as we think about justifying war and are faced with the horrifying results…Any war, no matter how victoriously prosecuted, is of course always a defeat for the civilized impulse, for the need to come up with other than violent resolution of conflict. And then there is the deadening of language that happens with the incessant barrage of public communication — “compassion fatigue,” in journalism professor Susan Moeller’s phrase.

But here I like to think of Maya Lin’s serene and wise description of how language is subverted, and memory served, by her brilliant memorial for the American dead of Vietnam:

But here I like to think of Maya Lin’s serene and wise description of how language is subverted, and memory served, by her brilliant memorial for the American dead of Vietnam:

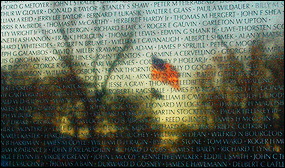

"I always saw the wall as pure surface, an interface between light and dark, where I cut the earth and polished its open edge. The wall dematerializes as a form and allows the names to become the object, a pure and reflective surface that would allow visitors the chance to see themselves with the names. I do not think I thought of the color black as a color, more as the idea of a dark mirror into a shadowed mirror image of the space, a space we cannot enter and from which the names separate us, an interface between the world of the living and the world of the dead."

Here is "Facing It," Yusef Komunyakaa's poem about encountering the Vietnam Veterans Memorial:

My black face fades,

hiding inside the black granite.

I said I wouldn’t,

dammit: No tears.

I’m stone. I’m flesh.

My clouded reflection eyes me

like a bird of prey, the profile of night

slanted against morning. I turn

this way — the stone lets me go.

I turn that way — I’m inside

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

again, depending on the light

to make a difference.

I go down the 58,022 names,

half-expecting to find

my own in letters like smoke.

I touch the name Andrew Johnson;

I see the booby trap’s white flash.

Names shimmer on a woman’s blouse

but when she walks away

the names stay on the wall.

Brushstrokes flash, a red bird’s

wings cutting across my stare.

The sky. A plane in the sky.

A white vet’s image floats

closer to me, then his pale eyes

look through mine. I’m a window.

He’s lost his right arm

inside the stone. In the black mirror

a woman’s trying to erase names:

No, she’s brushing a boy’s hair.

Even the title gives us some clue about the difficult act that the poem covers. Facing “it” is hard: first, the swelling tears have to be acknowledged, the hard swarm of the memories, and the realization that the black, glassy, and highly reflective surface of the memorial itself forces a look inside oneself, as well as a look outward, back to a specific name, to someone who went up in a white, booby-trapped flash. The memorial also insists that inside and outside the self are hard to separate, and that the separation of past and present is equally difficult, as we inevitably carry the past within our present. Among the other fusions that a visit to the memorial affirms, we are made to see that we are always at one with the living and the dead, and that as a nation, black and white, we face similar grief and loss. “I’m a window,” says the poem’s speaker; through me, other people’s losses come to the surface. At the memorial we meet as a community, however disparate.

And then, simply but powerfully, the poem moves to a self-correction. At first, a woman’s gesture reflected in the stone seems a hostile one of erasure. The woman is attempting to scrub away at the names. Then it becomes clear to the speaker, and to us, that the gesture is homely, loving, and domestic: a mother, presumably a surviving relative of one of the names, bends to comb a boy’s hair, to make him more presentable to the dead. It is an homage she is paying, and it is that unadorned homage and that respect with which the poet chooses to end.

Lorrie Goldensohn is the editor of AMERICAN WAR POETRY: AN ANTHOLOGY

(Columbia University Press) and the author of DISMANTLING GLORY: TWENTIETH-CENTURY SOLDIER POETRY (Columbia University Press), which was nominated for the 2004 National Book Critics Circle Award.