In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Drone Ethics

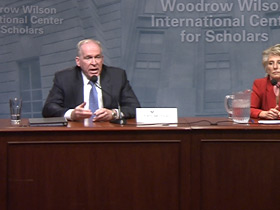

BOB ABERNETHY, host: In Pakistan, the U.S. government’s use of armed drones to target militants continues to strain relations between the countries. In the past, the administration has avoided talking about its drone program, but on Monday (April 30), a top White House official strongly defended use of the controversial technology. At the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, John Brennan, assistant to the president for homeland security and counterterrorism, called weaponized drones both legal and ethical and said their use is consistent with the country’s right to defend itself:

John Brennan: “There is nothing in international law that bans the use of remotely piloted aircraft for this purpose or that prohibits us from using lethal force against our enemies outside of an active battlefield.”

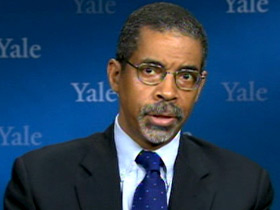

ABERNETHY: For more on this, Kim Lawton is here. She is managing editor of this program. We are joined by Stephen L. Carter, a professor at Yale Law School and author of The Violence of Peace: America’s Wars in the Age of Obama. He joins us from New Haven. Professor Carter, welcome to you.

PROFESSOR STEPHEN CARTER (Yale Law School): Thank you.

ABERNETHY: John Brennan said that the use of drones is legal, perfectly legal. You agree with that?

ABERNETHY: John Brennan said that the use of drones is legal, perfectly legal. You agree with that?

CARTER: I think the administration is right. We’re a nation at war, and in time of war a belligerent certainly has the right to target the leaders of the other side who are in the chain of command, and that’s what we are doing.

KIM LAWTON, managing editor: But if the battlefield in essence here has become the entire globe, how does that change the moral calculus of when and how the U.S. uses force justly?

CARTER: Well, I think you’re right that the more important questions are the ethical ones, and one of the ethical questions is how big the battlefield is, because the administration claims the right to target leaders wherever they may show up in the world. A second moral problem that arises is the problem of civilian casualties. Even if we have the right to go after leaders of Al Qaeda, we have to do it, both as a matter of law and as a matter of ethics, in a way that minimizes civilian casualties. The administration doesn’t actually count civilian casualties, so we don’t know how many there have really been. Mr. Brennan says that there have been times that they haven’t actually taken the shot because civilians have been in the line of fire, and if so, I’m glad to hear that, but I still think that we’d be better off if we could have a conversation in which we could talk more about the civilians who are killed. And there’s another ethical problem that we don’t spend enough time thinking about, and that’s the way that the drone war goes away from the front pages. It’s not on the evening news. In Iraq, we’re on the evening news. In Afghanistan, it’s on the evening news. With the drone war, it’s done in secret, it’s clandestine, it’s hard to keep track, and we really should know what’s being done in our name.

LAWTON: What kind of moral oversight would you like to see taking place surrounding this?

CARTER: At minimum, we members of the public ought to demand as much disclosure as possible from both our government, and also that the media cover the drone wars as closely as we cover other wars. There’s no greater and more difficult moral decision a nation makes than killing other people, and it’s quite important, if we are going to do that, that it remain in the forefront of our consciousness, that we not be distracted by other issues.

CARTER: At minimum, we members of the public ought to demand as much disclosure as possible from both our government, and also that the media cover the drone wars as closely as we cover other wars. There’s no greater and more difficult moral decision a nation makes than killing other people, and it’s quite important, if we are going to do that, that it remain in the forefront of our consciousness, that we not be distracted by other issues.

ABERNETHY: How do we know how many civilian casualties there are? Isn’t that a big danger, that this—that the use of drones will spill over and there will be a lot of civilian casualties?

CARTER: Because the administration doesn’t tell us when there are civilian casualties, or how many, it’s very difficult to keep track. We tend to rely on sources on the ground, some of whom have their own agendas and want to exaggerate it for one reason or another. But if we don’t know how many civilians are dying, we really can’t give a good assessment of the ethical principles that are underlying these attacks.

ABERNETHY: Professor, just very quickly, why now? Why did the administration come out with this now?

CARTER: There have been a lot of voices, including my own, that have been urging an open discussion of this. Because the administration has not acknowledged in the past that this drone program even exists, it’s hard to have public conversation about it. Now we can have an ethical conversation about it, and it’s high time that we do so.

ABERNETHY: Many thanks to Kim Lawton of Religion & Ethics Newsweekly and to Stephen Carter of Yale University Law School.