Sir John Polkinghorne on Science and Theology

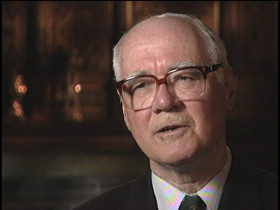

BOB ABERNETHY: Now, Perspectives today on one man’s view of the continuing struggle between religion and science. Sir John Polkinghorne is both a world-class physicist and an Anglican priest who says science can explain only part of what’s real. Chris Roberts has our profile.

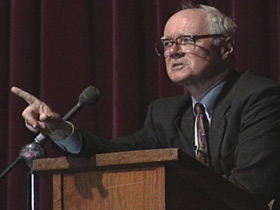

CHRIS ROBERTS: In a physics lab, a high-powered laser beam slices through a tank of water. For at least 400 years, the observations and tests of science, like a laser beam in turbulent water, have often churned through the teachings of religion. But now an eminent thinker on science and religion is casting new light on the controversy. He recently spoke at New York’s Cornell University.

Sir JOHN POLKINGHORNE (Scientist and Theologian): Science and theology have enough in common to find a mutual conversation and indeed a mutual friendship between them.

ROBERTS: Sir John Polkinghorne is a British mathematical physicist knighted by the queen for his scientific achievements. But he resigned his prestigious post at Cambridge University and became an Anglican priest. He says that his intention was not to repudiate science, but to seek the wider truth of religion.

Sir POLKINGHORNE: Both science and theology believe that there is a truth to be found about reality. They believe there is a truth to be sought and as far as possible to be found. Never, of course, totally to be found either in science or in theology.

ROBERTS: In the 17th century, Galileo challenged all prior cosmology by proving that the Earth revolves around the sun. In the 19th century, Darwin challenged the biblical story of creation by teaching that all life had evolved. Sir John says many scientists came to think that only science could discern truth.

Sir POLKINGHORNE: They think that religious belief can only be purchased at the cost of intellectual suicide because they think that religious belief involves this unquestioning assent to incredible propositions.

ROBERTS: But Sir John believes that religion can explain things that science can’t.

Sir POLKINGHORNE: Science is very successful and very important, and I want to take it very seriously. It’s very limited also.

And it can tell you some things. And there are things that we need to know which science can’t tell us about. Not just religion, but many other things as well. So I quite often say to my scientific friends, “What about music? What about music?”

If you ask a scientist as a scientist to tell you all that he or she can about music, they’ll say it’s vibrations in the air. And they can give you quite a very complete and exact account of the form of those vibrations. But we all know that that description, which is complete in scientific terms, has missed the whole mystery of music. Music is very, very much more than vibrations in the air. And so we have to have a wider view of reality that can embrace extra dimensions of music, which science, by its own choice, is unable to speak about. Religious belief is different from scientific belief in the sense that it involves the whole person. I believe passionately in the existence of quarks and gluons as smallest bits of matter. But that doesn’t affect the way I live my life. I can’t, however, believe in Jesus Christ without that affecting the way I live my life, as well as how I think about things. So, of course, religion is more overarching and more all-demanding than scientific belief can be.

ROBERTS: A poll taken 80 years ago showed that four out of 10 American scientists believed in God. That same poll was taken again last year. Surprisingly, after decades of scientific advancement, the results were virtually the same. Traditional beliefs had held steady.

Sir John sees differences between today’s physicists and cosmologists who are trying to explain the origin of the universe and the biologists who are using new discoveries, such as the structure of genes, to explain the nature of life.

Sir POLKINGHORNE: Physical sciences are at least open to the idea there might be a divine mind and purpose of some sort behind what’s going on. The biologists, on the other hand, are much more hostile to religion. DNA was a truly wonderful discovery. That has led biologists to think that everything is mechanical — that DNA is mechanical, animals are mechanical, everything is mechanical.

ROBERTS: So to some scientists there are intellectual obstacles to faith. For example, if the world works according to predictable, physical laws, can we really believe that God intervenes and answers prayers?

Can a scientist pray?

Sir POLKINGHORNE: Can a scientist pray is a question, of course, that one asks oneself, and I am a scientist, and I do pray. And we’ve always known, I think, as surely as we know anything, that we’re not automatons, that we have powers of choice. It seems to me that it is perfectly consistent, logically coherent that God can act within the openness of that physical world as well. And I think that in such a world, a scientist can pray.

ROBERTS: Sir John’s religious beliefs, like his scientific beliefs, are based on reason. The fact that he can accept the existence of God, he says, enables him to truly understand reality.

Sir POLKINGHORNE: Religion — or rather theology — is, I think, the great integrating discipline. It takes the insights of science — doesn’t tell science what to think — but it takes science’s insights and understandings, it takes the insights of morality, takes the insights of aesthetics, the study of beauty. The wonderful order or pattern of the world that science discovers and rejoices in is a reflection, indeed, of the mind of the creator, whose will and purpose lie behind the world. Our moral intuitions, our intimations of God’s good and perfect will, our experiences of beauty, I believe, are sharing in the joy of the creator, the creation. You can soon see the gross inadequacy of thinking that science can tell you everything that you could possibly know.

ABERNETHY: Chris, how was John received at Cornell, especially by students?

ROBERTS: Bob, I think he had broad audiences from many university departments, but he connected most with students who are studying to become scientists themselves. These are students who sometimes feel pressure to choose between their scientific ambitions and their faith. And here was Sir John, who understood their dilemma and could say, “Ha — be patient. You can think this through and work it out.”

ABERNETHY: How does he think the battle is going between religion and science? Does he think science is winning or religion is making a comeback? What does he — where does he come out?

ROBERTS: He might try and recharacterize it not as a battle, but as a conversation. He would say we should welcome truth wherever it comes from. And if religion can deal with questions of why, questions of purpose, and science can deal with questions of how, how the universe works, how our body functions, then between the two of them, properly understood, there should be a conversation, not a battle.

ABERNETHY: Chris, many thanks.

ROBERTS: Thank you.