In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Sufism

BOB ABERNETHY: There is a mystical tradition among Muslims that was once widely popular, drawing followers from every branch of Islam and from other religions too. It’s Sufism, which is under attack now by Muslim fundamentalists for being too liberal, but which is drawing more and more interest in the U.S. Deryl Davis visited a Sufi festival of teachings, readings, music, and dance in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

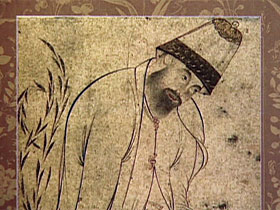

DERYL DAVIS: It’s best known in the West for the dance of the whirling dervishes. Sufism, which flowered within Islam more than a thousand years ago, is gaining new followers today in America. Sufism’s central ideas–universal love, mystical union with God, and openness to different spiritual paths–are being spread by teachers, musicians, and poets from around the world.

COLEMAN BARKS (Poet and translator, reading): What is the soul? Consciousness. The more awareness, the deeper the soul. And when such essence overflows, you feel a sacredness around.

DAVIS: For many Americans, Sufism is synonymous with Rumi, the 13th-century Islamic poet and philosopher whose writings have become best-sellers in translations by Coleman Barks.

DAVIS: For many Americans, Sufism is synonymous with Rumi, the 13th-century Islamic poet and philosopher whose writings have become best-sellers in translations by Coleman Barks.

Mr. BARKS: Just the mystery of the interior life, that’s what he’s talking about. Something as simple as love–and as mysterious.

DAVIS: The universal themes of Rumi’s poetry–love of God, compassion, and tolerance for others–are also what attract people to Sufism. It has no creed, liturgy, or specific theology.

Pir ZIA KHAN (Hereditary Leader, Sufi Order of North America): Sufism is fundamentally experiential. It is not based on intellectual premises. It is based on direct, personal experience.

DAVIS: Pir Zia Khan is hereditary leader of a Sufi group, or order, originating in India. His grandfather is credited with bringing Sufism to the West.

Pir ZIA: He presented the Sufi message as an essential awareness that could be discovered in the essence of all of the major world religions.

Pir ZIA: He presented the Sufi message as an essential awareness that could be discovered in the essence of all of the major world religions.

DAVIS: While Sufism has attracted new followers in the West, its influence has greatly declined in the Muslim world. Carl Ernst says Sufism was integral to Islam up until about 200 years ago.

Dr. CARL ERNST (Chair of Islamic Studies, University of North Carolina): Sufism was part of the normal fabric of life in any Muslim city or country, and if you had visited Mecca a little before 1800, you would have found most of the Islamic teachers in the principal institutions in Mecca and Medina belonged to Sufi orders. But changes have taken place in the last couple of hundred years.

DAVIS: One of several changes is the rise of Islamic fundamentalism. Scholar Akbar Ahmed says there’s an inherent clash between the pluralistic vision of the Sufis and the strict doctrine of figures like Osama bin Laden, for whom Sufism is heresy.

AKBAR AHMED (Islamic Scholar, American University): The central message of the Sufi is sole cul, “peace with all,” and the message of the Sufi resonates outside Islam itself. And that is why there’s a confrontation, a tension, between the orthodox who would want to interpret Islam in a literal way and the Sufis, who would want to expand the boundaries of Islam to include all humanity.

AKBAR AHMED (Islamic Scholar, American University): The central message of the Sufi is sole cul, “peace with all,” and the message of the Sufi resonates outside Islam itself. And that is why there’s a confrontation, a tension, between the orthodox who would want to interpret Islam in a literal way and the Sufis, who would want to expand the boundaries of Islam to include all humanity.

DAVIS: Pir Zia was invested as head of his order two years ago at the shrine of a famous Sufi saint in India. Sufism’s mystical teachings about mastering the self and developing spiritual insight are handed down from generation to generation by special teachers or guides.

Dr. ERNST: The master-disciple relationship is basic to the entire enterprise of Sufism. There is an astute psychological wisdom here in that it’s impossible for someone to overcome their own ego, and so you need someone who has moved to a higher level to be able to do that.

DAVIS: While Sufi teaching differs from group to group, all orders share a common practice called zikr–ritual meditation on one of the 99 “beautiful names” or attributes of God.

DAVIS: While Sufi teaching differs from group to group, all orders share a common practice called zikr–ritual meditation on one of the 99 “beautiful names” or attributes of God.

LUA HIGHTOWER (Sufi musician): It’s a way of being mindful of the presence of God, and by focusing on a particular attribute, you can access a certain state, or sort of develop a certain quality in yourself by invoking that name over and over and over again.

DAVIS: The famous whirling dance, practiced by only one of the many orders of Sufis, is itself a form of zikr.

RUPA COUSINS (Sufi dancer): It is a moving prayer and a moving meditation, that’s the idea, is to dissolve into the energy of God, into the energy of prayer. The right hand in this dance reaches up to God, to the divine. The left hand reaches out to give, and so we’re giving a blessing to the world as we turn.

DAVIS: The dance is layered in symbolism. The hat suggests a tombstone, the end of earthly existence. The flowing white garment represents the freedom that comes with spiritual rebirth.

Today, some western practitioners of Sufism are not Muslims and may know little about its connection to Islam. Many are attracted by Sufism’s music and poetry, as well as its openness to different spiritual views.

Today, some western practitioners of Sufism are not Muslims and may know little about its connection to Islam. Many are attracted by Sufism’s music and poetry, as well as its openness to different spiritual views.

COLEMAN BARKS (Poet and translator, reading): Let the beauty we love be what we do. There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground…

Mr. BARKS: You can’t go to a Sufi church. There is none. There’s no Sufi doctrine. It’s just–I call it the love religion, where the…your relationships are with the unseen and with the seen, are your text. That’s the sacred book that you must read and interpret.

Mr. AHMED: If Islam can strengthen the Sufi message, then Islam has a very positive role to play in the 21st century. If it doesn’t, society itself is depleted, and society loses perhaps the most authentic voice of Islam, which has integrity and which speaks for all humanity.

DAVIS: Some observers say they hope Sufism as practiced in America today can be reborn in the Islam of tomorrow.

I’m Deryl Davis reporting.

ABERNETHY: Sufism’s whirling dancers say they don’t get dizzy, and there aren’t in a trance. It’s all about concentration.