In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

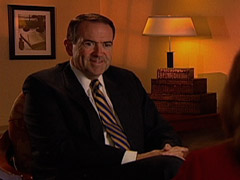

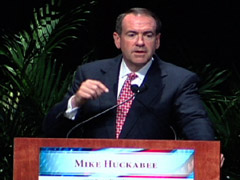

Interview: Mike Huckabee

Read more of Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly correspondent Kim Lawton’s September 16, 2007 interview with Republican presidential candidate Mike Huckabee:

Q: Well, I’m a little curious how your experience as a pastor is helping you on the campaign trail as you seek the presidency?

A: I think it’s a great background in part because there’s not any social pathology that exists today that I couldn’t put a name and a face to. Doesn’t matter whether it’s a teen girl who’s pregnant, hasn’t told her parents, or an elderly couple dealing with one of them being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Those are real people to me. Those are the people I dealt with every single day. So that period of my life where I was literally touching people’s lives from the cradle to grave is probably the best way I could have ever been prepared to deal with the job that ultimately is about dealing with people and understanding the incredible frailties and complexities of life.

Q: How does your faith inform your politics?

A: The best way is to say that as a Christian for me the essence of Christian faith is that you treat others as if you wish to be treated. That was the ultimate commandment of Jesus — to love God with your whole heart, to love others as you would love yourself, and to treat others as you would wish to be treated. That’s really the heart of the Gospel. So if a person is in public office your ultimate question is not how should this affect me, but if I were that person how would I want someone to deal with this issue in such a way as to best benefit that person? I think it gets easier for me. Public policy is pretty easy when you ask, you know, what would I have them do unto me?

Q: What role does prayer play in your decision-making process?

Q: What role does prayer play in your decision-making process?

A: Prayer’s important, not just as some kind of a metaphysical exercise, but I think it’s a way to refresh one’s own mind and motive. If you’re praying, you’re really looking beyond your own personal thoughts and the pressures that are around you. You’re trying to get a focus on a perspective that’s higher than your earthly one. You’re trying to see things that are bigger than you, that are more important than you. You remind yourself that, you know, there was a world here before I came along, and there will be one after I leave. I’m not that important, but the decision I make may be, so I need to make the right one.

Q: Does it affect, though, how you come down? I mean, do you think that prayer has an impact on where you ultimately come down on your decision?

A: Oh, I would hope so. I would hope that prayer certainly lets me see things not so much from a selfish perspective. That’s the main thing, to take it away from my own nature, which is that of every person, to look at things from one’s own personal perspective as if the world’s about me. Prayer reminds me it’s not just about me. It’s about all the people with whom I share this planet, and all of whom God has created, and all of whom he cares just as much about as he cares about me. He loves me no more than he does anybody else. He loves them no less than he does me. So if I’m a person of prayer, I’m going to be reminded of that because that ultimately is what prayer does. It just takes us to a level of higher thought than our own personal selfishness.

Q: What do you say to people who believe that a minister shouldn’t — a former minister — shouldn’t be president? How do you reach out to potential voters who say, “I can never see myself voting for a former Southern Baptist pastor”?

A: I can’t imagine that there’s still that much bigotry in this country as it relates to religion. I would hope not. It would be like saying Martin Luther King should have kept his mouth shut ’cause, after all, he should have stayed in the church and not preached justice and righteousness. Do we really say that about him? I’ve never heard it said. Interestingly, most of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were ministers or were very active in their church, but many of them were actual ministers in their church. For us to somehow act like that people of faith are disenfranchised from being in the public square, again, I would find that disturbing, as if there is sort of a unspoken bigotry toward people of faith. And, furthermore, if that’s the case then, you know, if I’m not going to be exempted from having to pay taxes and living in the real world like everybody else, then don’t shove me to the side. In the case of my particular candidacy, it’s not like I’ve just stepped from the pulpit to run for president. I was a lieutenant governor three years. I was a governor ten and a half. Among the Republicans, I actually have more executive government experience than any other single candidate running for president. Mayor Giuliani sometimes talks about his executive experience. He was a mayor eight years. I was in public office as an elected official for eleven and half, ten and a half of which was the chief executive of my state.

Q: How have you learned as a politician, or what guidelines do you try to employ in your language when you speak about religion so as to include or not alienate people who don’t share your particular beliefs?

A: I understand that there’s somewhat of an anxiety with certain people because I have an outspoken view on faith. I think I try to disarm people on the front side rather than wait on them to ask the question “how does it affect you?” And sometimes I’ll begin speeches in front of audiences that I can sense the tension by just sort of getting it out of the way and talking about look, don’t let this be something that you fear, and I’ll explain why it’s not to be feared, and that is, is because like every other person I’m being honest and open about my faith and how it impacts and how it affects me. I don’t worry about people who talk about their faith. I worry about people who say they have it but they refuse to say that it affects them. To me that’s disingenuous, or it’s somehow indicative of a person who’s almost ashamed of his or her faith. If it’s real faith it’s a part of our lives. We should be comfortable talking about it, just like I’d be comfortable talking about my allegiance to the Arkansas Razorback football team. That’s not difficult for me. Why should religion be so difficult for me to talk about? It doesn’t bother me if the person says, “I just don’t find it important to me. I’m running for office, but I’m an atheist.” You know what? I would rather a person be honest and be an atheist than claim to be a Christian but then act like they can’t talk about it ’cause they’re almost embarrassed to bring it up. That’s troubling. If a person says here’s a part of my life, it’s fundamental to every breath I take, that really defines my world view, and yet I’m uncomfortable discussing it with anybody, I’d worry about a person whose faith is so shallow or so insignificant that they can compartmentalize their entire faith as if it doesn’t matter to them.

Q: There actually has been a lot of God talk this campaign season. We’re hearing a lot from the Democrats who in the recent past have been a little maybe skittish about dealing with issues of faith. How do you assess the role religion’s been playing in this campaign, especially maybe compared to, you know, others in recent history?

A: I think it’s healthy. I’m glad to see that Democrats are talking openly about faith, and I don’t think it’s dishonest or disingenuous. I think it’s, frankly, refreshing. In the past it seems the Democrats were afraid to talk about faith from a personal perspective, and I don’t know why. I would think that it’s something, again, that helps people to get to know you. And whether a person says, “Look, here’s my faith and here’s what I believe and here’s how it affects me” or even to say, “I don’t really have much of a faith, so it’s not a big issue for me,” I think what people look for is candor out of their candidates. They just want somebody to be honest with them. So if a Democrat has faith, and they really personally practice prayer, and they’re regular church goers, why shouldn’t they tell us that? I think they should, and not a matter of that we ought to vote for them because of that, but just so that we get to know them a little bit. But I welcome it. I think it’s a healthy part of the discourse in this campaign.

Q: Does it — is there a danger that it might hurt some of the Republican base of religious voters?

A: I don’t think so, and if it does, it does. It’s still a good thing. You know, I was asked early on when there was a discussion that Hillary Clinton had about her faith, and someone asked me about that and did I think it was genuine and I said why wouldn’t I think that? She was candid enough to discuss it. I think it plays a very important part of her life, and I respect that and, you know, her faith is practiced in a Methodist Church and mine is in a more contemporary Baptist congregation where we’re in some ways more charismatic. But, as I said, some people eat their soup louder than others. It doesn’t mean that the soup tastes any better. It’s just a matter of how we approach it. That’s why I think sometimes it’s important for us to talk about it openly. Let people see that there are different, maybe, viewpoints and theologies and worship styles. The key thing, though, is being refreshingly candid so that we can let people look in on us, and if they decide that that makes us a nut because we believe there’s a God, so be it. Let them believe that. I’m more than willing to be laughed at for my faith if that’s what people wish to do. I’ve been laughed at before. But what I would, I guess, be more pained by would not be to be laughed at for my faith, but would be to be ignored for it.

Q: What do you — what does learning about a politician’s faith teach the voters? You know, why is that important information for a voter?

Q: What do you — what does learning about a politician’s faith teach the voters? You know, why is that important information for a voter?

A: Mostly to let them know what their value system is. Where do they get their values? Is it from the latest opinion poll? Is it from an academic study which would change with every few years in terms of a new academic study? Or are there some things in a person’s life that they believe are inherently right, or things that are inherently wrong? And if so, why are they right or wrong? And what’s the basis of believing that? You know, if a person doesn’t have some type of sense of moral absolutes and everything is relative, that’s a signal to a potential voter that here’s a person that no matter what he tells you, just remember that he’s willing to adjust as culture and society adjust. If a person has a God-centered view of the world and believes that we really do have accountability ultimately not just to each other but to a Creator God who was here before us and will be here after us, then that does shape, in fact, how we look at life, and I think that’s important for voters to know.

Q: Why do you think religious conservatives haven’t rallied around you stronger than they have, given that you share so much of what they believe?

A: I think that in some ways the Christian conservative movement has maybe gotten off the track. I think that some of them, frankly, are more intoxicated with power than principle, and I know that’s a pretty outrageous if not rather bold statement to make, but I think it’s the truth. Some have become so acquainted now with power and have been so close to it that they forget that the purpose for which they got involved in politics was not to be close to power; it was to speak the truth to power. It was to hold those in power, to hold their feet to the fire over issues they said got them involved and motivated. Now I hear some of the so-called Christian leaders say, “Well, we love Huckabee. He really agrees with us, and he’s one of us in terms of views. But, you know, we’re looking for somebody that we’re confident is going to win.” Well, two things. First, a lot of these people if they would get behind me I’d be winning right now, and I think I will ultimately without them. But secondly, if they really are principled, it’s not about who might win, it’s about who stands with us. And, frankly, it’s a little disturbing, if not frightening, that some have forgotten the essence of what Jesus taught, and that is if you gain the whole world but lose your soul what does it profit you? And, frankly, some who would say, “Well, the presidency is so important.” You know, well, so what? The presidency is not as important as are your values and as are your deep principles from the heart. And I worry about people who have come to this sort of “it’s about winning.” No. It’s about standing for your convictions. And if it’s not about that, then I’m afraid that many people got involved for all the wrong reasons.

Q: Do you think they’re afraid of losing their place at the table?

A: Yeah, and the tragedy is that what place at the table is there if the people who are elected don’t share your convictions and therefore may give you some lip service in order to get elected? They’re not going to waste any of their time and capital and energy trying to accomplish your agenda, because it’s not their agenda, and that’s what’s happened to conservative Christians in the past. They worked real hard to get someone elected because the person knows how to go speak to them, but the person doesn’t know how to speak for them. A person maybe runs for office, and he goes and presents himself to that Christian community for votes. But there’s a difference if that person comes from that Christian community in really understanding it. It comes down to whether the language of the church is a second language for the candidate or if it’s the native tongue.

Q: Some of the issues that are so important to that community — abortion and gay marriage are two that seem to be up there. Are they as important in this election? Should they be that important?

A: They’re important from the standpoint of giving people an understanding of where your values are and where your convictions come from. Again, if you believe that there are certain moral absolutes in the universe, then you have to believe that to take an innocent human life for one’s own convenience sake would be immoral. And yet I think also the pro-life community of which I’m a part has to grow up and also articulate that being pro-life is not just saying that we care about a child as long as it’s the womb, but as soon as it comes out, “Hey, kid you’re on your own, and if you’re sleeping in the back of a car, if you’re getting the daylights whacked out of you by an abusive parent, well, that’s not of issue to us.” Well, it better be, because pro-life means more than just life inside the womb and during the gestation period. It means whether that child is living in a safe neighborhood, whether its schools are properly preparing him for a world out there, whether he’s hungry, whether he’s got a blanket over him at night. And so in many ways one of the things that I try to do is to articulate that being pro-life is not just about being anti-abortion. It’s being pro-life. It’s not articulating what we’re against but more focusing on that for which we are for, and that is the worth and the value and the importance of every single human life — that each person has intrinsic worth in and of themselves not tied to somebody else’s worth, but their own unique worth and value. That’s what separates us as a culture, as a people. It’s what makes us care about six miners in the womb of a coal mine in Huntington, Utah. But it also ought to make us care about that unborn child in the womb of a mother.

Q: Some evangelicals are trying to broaden the political agenda to include more than these issues and you’ve — sometimes a lot of your language seems like you’re doing that as well. Where do you see that, you know, broadening the values agenda?

A: Well, we had better broaden, ’cause I think Jesus did. Jesus was more concerned about people being impoverished and people being mistreated and exploited. Those are real issues, and if we as Christian believers, particularly those of us who get involved in public policy, if we turn a deaf ear to people whose lives are being exploited, whether it’s in some easy credit scheme, whether it’s in the fact they’re exploited for their labor and they work real hard for a company only to see the CEO take off with a $200 million bonus while they lose their paycheck and pension, for me that’s a moral issue. How can you justify a hedge manager making 2200 times that of the average worker or a CEO making 500 times that of an average worker? You know, I’m a capitalist, but capitalism doesn’t have to also equate with greed. And what we see in some cases today is not simply the good kind of capitalism that built a strong American economy. But it’s the raw, unadulterated, sheer greed that says I’m going to be a super winner, and I don’t care if all the people who help me get there are going to be super losers and can’t even feed their families. That ought to be a moral issue. And there are other things. We ought to be, as Christian believers, we ought to be concerned about the environment. I think, frankly, the Christian community has a lot to answer for, for not being stronger advocates of better care of the planet for the simple reason that if I’m true to my faith, I don’t believe this world belongs to me. Last time I checked it wasn’t mine. It belongs to the Creator, and I get to live here. I’m, let’s say, a guest, a visitor, but I don’t have the right to tear it up, not leave it in good shape for the next generation.

Q: I’ll move overseas. I know you’ve talked about the value — the war against Al Qaeda in Iraq has a real, you’ve said, theological aspect to it.

Q: I’ll move overseas. I know you’ve talked about the value — the war against Al Qaeda in Iraq has a real, you’ve said, theological aspect to it.

A: Yes.

Q: What do you mean by that?

A: Well, part of this war is not geopolitical. Most wars are fought over borders and boundaries and maybe over political leadership –who’s going to get to be the king or who’s going to get to be the, you know, the dictator? This is not fought that way. This is really a war without national boundaries. We’re not fighting in a particular geographical location. Al Qaeda’s alive and well in cells all over the world, on every continent and in every country. And what I mean by a theological war, it’s been driven not by a goal simply to establish a geopolitical base for a country and a constitution, it’s being fought over by religious fanatics and jihadists who believe that there is total marriage between religion and state and that to implement one is to implement the other. That’s quite foreign to the American who doesn’t really sometimes understand what we’re up against and what the nature of the fight is about. Because they tend to want to westernize this whole war and make it like we would understand a war. Well, it isn’t, and if we don’t get that, it’s going to be a long and painful process for us.

Q: Some American Muslims are a little uncomfortable when they hear language about “the jihadists.” You know, they worry about how — the impact of that language on them in their community. Well, you know, how do you — what do you say to them?

A: Right after 9/11, I was governor [of Arkansas], and I called all the religious leaders of the Muslim faith to come and join me at the capitol for a meeting at the governor’s conference room, and I held a press conference, and I asked the people of Arkansas don’t hold these people responsible for what radicals within their greater umbrella of faith are about. I think you’d find an incredible of level of support in my home state among Islamic leaders because they know that no one was quicker nor more strong to their defense after 9/11 than I was. What I think that the Islamic leaders need to do — the legitimate and serious and moderate leaders — is to take a very bold and public stand against the jihadists. Nobody can do it with more credibility. No one can better help to show that there is a real difference between the radical jihadists and people who practice Islam as a matter of personal preference than could the imams and others who can articulate that.

Q: I’m wondering what you miss most about Beach Street Baptist Church [in Texarkana]?

A: I think probably the, just the sort of closeness of the community that one has in a local church. And as a pastor you really were such a part of the fabric of people’s lives, the best and the worst of moments. And there was a sense of belonging that was based not on people who are questioning your every statement and every move, but who loved and wanted you to be a part of their life. The big difference between politics and pastoral ministry is that in both cases you’re on a pedestal. But my wife once said it best when she said that you’re on a pedestal both places, but in the church they want you to be on that pedestal. They appreciate you’re being there, and they fight to keep you there. They want you to do well. In politics you’re on the pedestal, and all kinds of interests are doing everything they can to knock you off of it, so you’re constantly sort of having to be on your guard or fear of what’s out there.

Q: Are you able to get to church very often on a campaign trail? How do you try to do that?

A: Yeah. I try to always make it a point to be in worship. When I travel, I typically will try to make sure that I can be in a church on Sunday. If for some reason I’m traveling on Sunday and can’t, you know, there are times it’s unavoidable. But if I’m home in Little Rock I’m always in my own home church [The Church at Rock Creek], which I wish I could be at more often, because I absolutely love my church. We have a magnificent congregation. It’s only about 11 years old. It started with 25 people. It now has over 5,000 people worshiping there every weekend and just a phenomenal group of people who reach out to about everybody imaginable. And it’s quite a homogeneous church of people that I often say you just will find the greatest level of diversity there, and that’s what I think attracts me to it so.

Q: When you’re on the campaign trail and there’s so much pressure and everything, how do you keep your own spiritual fires burning?

A: I try to maintain a daily time of devotion in my own life, prayer and meditation, and try to read a chapter in the Bible every day. One thing I’ve done since I was 18 is read a chapter in Proverbs every day, and with 31 chapters you go through the whole book each month, and it’s a great source of wisdom to stimulate your thought and to make you think thoughts higher than what you’re going to get from the front page of the paper. But I also find that it’s just important to be surrounded, too, by people to whom you’re accountable, and there are several close friends that have been my friends long before I ever got into politics who have a sort of unfettered access to me and the right to challenge me personally, who will contact me either by phone or by e-mail or however they can get a hold of me and just to check up on me, and that’s important.

Q: What has running for president taught you spiritually?

A: Well, I guess the main thing I’ve learned spiritually is that it requires an extraordinary level of stamina that I don’t naturally have, and I don’t think anybody does. But the other thing I’ve learned maybe from a spiritual standpoint in running for president is that nobody has all the answers. People sometimes expect if you’re running for president you can answer every question about everything — that you’re going to know everything. The truth is no one of us do, and I think rather than fake it sometimes it’s just important to say I don’t know. I don’t know. And that’s the best answer, because it’s the most honest one.