In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Mending Medicare

BETTY ROLLIN, correspondent: For years, Natalie Albin endured aggressive treatment for leukemia. She wound up in Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York. Death was near.

FRAN CRONIN: She’d had years of chemo. She was done with it. There was nothing left for her body to tolerate.

ROLLIN: Her daughter, Fran Cronin, says that what the family wanted at this point was a quiet time to be together and say goodbye.

CRONIN: But the doctors kept on coming back to us and asking us if we’d like to do tests, what else we could do, and we’d have to say, well, what kind of difference will this make? Is this going to change the prognosis? No. This might extend her life for a couple of months. What quality of life is she going to have? Nothing really better, can’t guarantee. In our effort to say goodbye to my mother we were always being interrupted by the hospital’s own need to be service-driven. They weren’t about hospice care. It wasn’t about saying goodbye. Their role and their interaction with us was to provide treatment.

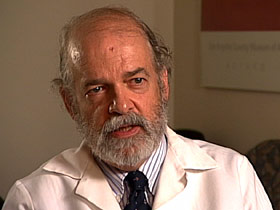

DR. LACHLAN FORROW (Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital): We are wired as human beings, thankfully, to when in doubt you fight for life no matter what. Doctors and nurses are trained, first we want to try to save a life.

DR. LACHLAN FORROW (Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital): We are wired as human beings, thankfully, to when in doubt you fight for life no matter what. Doctors and nurses are trained, first we want to try to save a life.

ROLLIN: While the person whose life is being saved wants to be kept as comfortable as possible, he or she doesn’t necessarily want to be saved, and often this hasn’t been made clear to either the doctor or the patient’s family. Dr. Lachlan Forrow is director of ethics and palliative care at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital in Boston.

DR. FORROW: The tragedy is our health care system does not provide any context to help doctors and nurses have the time to talk with people about these hard things, and the whole system is greased to pay hospitals and others for expensive things people might not even want. One of the fundamental problems is what gets called our fee-for-service system. Doctors and hospitals get paid for the things that they do that tend to be expensive. The more expensive it is, the more you get paid.

ROLLIN: Our medical system can’t keep everyone healthy, but it excels at keeping people alive, which is expensive. Twenty-five percent of all Medicare spending is for the 10 percent of patients who are in their final year of life. For the year 2012 alone, that’s expected to be $137 billion. Most of the money is spent in the last 6 months of life, which is often of little benefit, if any, to the patient. And the conversations between patients and doctors and family members which might make a difference, Dr. Forrow says, aren’t happening, partly because people are afraid to talk about death and because the part of the Obama health care reform plan, which would have reimbursed doctors for these conversations, was shot down.

DR. FORROW: Cheap, political, inflammatory comments like “death panels” and “pulling the plug on grandma” for cheap political points have terrified the American people in a way that I think—I think that’s immoral.

ROLLIN: Dr. Susan Mitchell, who has studied advance dementia in nursing home patients, has found that even though these patients can be treated and kept more comfortable in a nursing home, they are often hospitalized where they receive aggressive and sometimes painful treatment that is covered by Medicare.

ROLLIN: Dr. Susan Mitchell, who has studied advance dementia in nursing home patients, has found that even though these patients can be treated and kept more comfortable in a nursing home, they are often hospitalized where they receive aggressive and sometimes painful treatment that is covered by Medicare.

DR. SUSAN MITCHELL (Senior Scientist, Hebrew SeniorLife): The nursing home does not get reimbursed for taking care of a patient who’s acutely ill with advanced dementia, which can take a lot of staff time and resources. So it’s at no cost to them to send them to the hospital where they will get that care.

ROLLIN: The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that the cost for dementia care in 2011 will be approximately $183 billion, mostly paid by the government, and that cost will go up to $1.1 trillion in 2050.

DR. MITCHELL: I think there’s a lot of unnecessary and costly medical care being provided for patients with advanced dementia that is not what the families and patients want.

ROLLIN: But even if patients and their families have expressed their wishes, that doesn’t solve the entire cost problem.

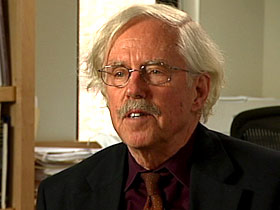

PROFESSOR DAN BROCK (Harvard Medical School): At the end of life, people often have greater difficulty in giving up, in no longer using resources, and so you hear this notion, particularly from families, “I want everything done,” and implicitly there, or sometimes explicitly, “Don’t worry about the cost,” right?

ROLLIN: Professor Dan Brock, who teaches ethics at Harvard Medical School, is one of the few who believes America must ration covered health care based on efficacy and cost.

PROFESSOR BROCK: I was once at a meeting in Britain many years ago with British physicians, and we were talking about end-of-life care decisions, and the Americans asked, “Well, what do you do when patients demand or when families demand?” And the British docs sort of looked bemused and said, “Well, they don’t do that here. They don’t demand here.” We have insurance, so we say we’re entitled to it, and we have this view that rationing is a bad thing to do, and so we think we ought to get it.

PROFESSOR BROCK: I was once at a meeting in Britain many years ago with British physicians, and we were talking about end-of-life care decisions, and the Americans asked, “Well, what do you do when patients demand or when families demand?” And the British docs sort of looked bemused and said, “Well, they don’t do that here. They don’t demand here.” We have insurance, so we say we’re entitled to it, and we have this view that rationing is a bad thing to do, and so we think we ought to get it.

ROLLIN: The problem is more acute when the patient is dying.

PROFESSOR BROCK: Should we cover this new cancer drug which extends life on average for three months and costs $200,000 or $300,000 to do so? And when you look at it that way, then people can begin understand that, well, it doesn’t seem to make sense.

ROLLIN: And the other difficulty, Professor Brock adds, is that once a drug is considered safe, Medicare does not consider cost in their approval of coverage. They ask only whether the treatment is “reasonable and necessary.”

PROFESSOR BROCK: Medicare is not able to deny coverage on grounds that—what’s usually called cost effectiveness. That is, the cost isn’t merited by the benefits.

ROLLIN: Many experts say if the question of cost is not dealt with it will surely get worse because of new treatments, which will be more expensive. Also, a growing population of the aged and their physicians will want these treatments, no matter the cost to Medicare.

For Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly I’m Betty Rollin in Boston.