In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Eliza Griswold on the Muslim-Christian Divide

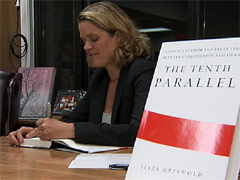

KIM LAWTON, correspondent: There’s been a lot of theorizing about the conflict between Islam and Christianity—what some have called a “clash of civilizations.” Journalist and poet Eliza Griswold wanted to learn about the conflict for herself up close and personal by talking to real people in the midst of it all.

ELIZA GRISWOLD: I wanted to go to where the world is really breaking apart. I wanted to go see what happens when these two religions meet on the ground in villages, mega-slums, floods, droughts. I really feel that I’ve seen that the world is breaking down on tribal lines, and the greatest of those tribes is religion.

LAWTON: Griswold spent the past seven years reporting from what she considers perhaps the biggest faith-based fault line in the world—the tenth parallel, the line of latitude 700 miles north of the equator in Africa and Asia.

GRISWOLD: These are very contested spaces traditionally, and religion has become grafted onto what makes them so contested today.

GRISWOLD: These are very contested spaces traditionally, and religion has become grafted onto what makes them so contested today.

LAWTON: The area includes Nigeria, Sudan, Somalia, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines—all places of bloody battles between Muslims and Christians. Griswold says geography, climate, wind patterns and human migration have led to clear lines of demarcation.

GRISWOLD: When we think of Islam we think of a billion people around the world. We don’t usually think that four out of five of those people live outside of the Middle East. They’re not Arabs. They live in Africa, and they live in Asia, and then you have about half of the world’s two billion Christians who also live in what we call these days the Global South.

LAWTON: Along the tenth parallel, both Christianity and Islam have been experiencing an explosive growth in numbers and religious fervor. Griswold wanted to examine whether fundamentalism necessarily leads to violence.

GRISWOLD: The belief that there is one and only one way to find God, and the understanding that that leads immediately to an enemy, because everybody else is wrong. That kind of binary division between us and them, the saved and the damned, I wondered if that was inherently violent because you were setting yourself against another person.

LAWTON: Griswold’s explorations were deeply influenced by her personal background. Her father, Frank Griswold, is an Episcopal bishop who from 1998 until 2006 was the top leader, the presiding bishop, of the US Episcopal Church.

LAWTON: Griswold’s explorations were deeply influenced by her personal background. Her father, Frank Griswold, is an Episcopal bishop who from 1998 until 2006 was the top leader, the presiding bishop, of the US Episcopal Church.

GRISWOLD: I grew up with a lot of fear about what God’s will would mean. You know, after being a 12-year-old and watching my dad be consecrated as a bishop in the Episcopal Church, which involved lying face down on a cathedral floor with his arms out in a crucifix shape. That terrified me. If I submitted to God’s will, what would God ask me to do?

LAWTON: Griswold says her family encouraged wrestling over questions of faith and intellect.

GRISWOLD: How does the mind work in relation to God? How do all kinds of people believe in God? And how does intelligence apply to that? That notion very much is at the center of what sent me looking along the tenth parallel. So is the idea that people can believe in God absolutely without necessarily being dangerous or without necessarily there being a way to explain their faith away.

LAWTON: Her journey began in 2003 in Sudan, where nearly two million people had been killed in a civil war between the predominantly Muslim North and the predominantly Christian South. Two years before the war ended, Griswold traveled there to observe a meeting between evangelist Franklin Graham and Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir. She says Bashir was afraid the US would invade Sudan, while Graham wanted permission to do evangelism in the northern part of the country.

LAWTON: Her journey began in 2003 in Sudan, where nearly two million people had been killed in a civil war between the predominantly Muslim North and the predominantly Christian South. Two years before the war ended, Griswold traveled there to observe a meeting between evangelist Franklin Graham and Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir. She says Bashir was afraid the US would invade Sudan, while Graham wanted permission to do evangelism in the northern part of the country.

GRISWOLD: The trip itself was fascinating to me, because it was what happens when faith and foreign policy become interlinked. And it’s something we’d heard a lot about, certainly during the Bush administration, but both before, because this is a history that dates back to colonialism, and also still today there’s quite a strong religious lobby that works strongly in our foreign policy that we don’t always see.

LAWTON: You talk in your book about many people saying to you this isn’t really a conflict about religion; it’s a conflict about oil, or water, or politics, resources. How much is religion truly a factor in some of these conflicts?

GRISWOLD: It’s almost an impossible question to answer because I have found that each conflict is different. I never saw a conflict that we would see as religious that didn’t have some kind of secular or worldly trigger—whether that’s land, oil, water, even chocolate crops in Indonesia. Now does that mean that religion doesn’t come to bear on these conflicts? It’s more complicated than that.

LAWTON: Adding to the complexity, she says, are clashes within the religions.

GRISWOLD (speaking at bookstore): There is a very profound religious clash that we’re missing. It is not the clash between Christianity and Islam. It is the clash inside of religions. It is the question between Christians over who has the right to speak for God. Those same questions are going on inside Islam today, and yet we don’t hear very much about it.

GRISWOLD (speaking at bookstore): There is a very profound religious clash that we’re missing. It is not the clash between Christianity and Islam. It is the clash inside of religions. It is the question between Christians over who has the right to speak for God. Those same questions are going on inside Islam today, and yet we don’t hear very much about it.

LAWTON: Griswold saw religion being used to fuel violence, but she also saw it used as a force for reconciliation.

GRISWOLD: One of those places is in northern Nigeria, this town of Kaduna, where a pastor and an imam worked together to really transform one of the most violent fault lines along the tenth parallel into one of the most peaceful ones. How did they do that? Community building.

LAWTON: She says the pastor reminded her that events in the US and other parts of the West can have repercussions around the world.

GRISWOLD: He me told me this quote that I just find so relevant now, which is when the West sneezes Africa and Asia catch the cold. So what does that mean, really? Well, that means quite viscerally, for example, with the cartoon riots, the Danish cartoon riots several years ago, more people died in Nigeria than any other country around the world.

LAWTON: After seven years of talking to people on the front lines, Griswold says she didn’t discover any easy answers about the volatile mix of religion, politics, and violence.

GRISWOLD: What I probably took away is certainly empathy, but also—it’s a hard word to use because it comes with so much baggage—but a lot of humility, I guess. Because I didn’t feel myself in a place to intellectually judge people’s lives, although I began thinking—I didn’t even question that I would be able to sort of assess what people were up to by assessing their sociology, and in truth I couldn’t.

LAWTON: But she did come to see, as she writes in her book, that “religions, like the weather, link us to one another, whether we like it or not.”

I’m Kim Lawton in Washington.