In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Timbuktu

BOB ABERNETHY, anchor: Now, a reporter’s pilgrimage. Of all the world’s remote datelines, surely Timbuktu must rank close to the top. It’s in the West African nation of Mali, where the Sahara desert meets the grasslands. Fred de Sam Lazaro went there, and found a story. Long ago, it seems, Timbuktu was a place of high Islamic scholarship, and it still has a million manuscripts to prove it.

FRED DE SAM LAZARO: For most Americans, Timbuktu has long stood for, well, nowhere — a place far, far away, probably in fiction.

But deep in the West African nation of Mali, where the savannah grasslands meet the Sahara, lies Timbuktu. It’s an impoverished town of about 30,000, most of them nomadic traders or subsistence farmers. But Timbuktu is rich in history — history that contradicts a commonly held impression in the West that sub-Saharan Africa has only oral and no written traditions.

Professor SALEM OULD EL HAJJ (Through Translator): Well before there was an America, Timbuktu was a thriving center of learning, with the university. Professors were teaching philosophy, theology, mathematics.

DE SAM LAZARO: Professor El Hajj says the earliest records of Timbuktu go back to the 11th century, to a prosperous desert crossroads where salt, gold, slaves, and scholarship were exchanged. That all ended in the late 1500s with Moroccan invasions and later French conquest.

Today, much of Timbuktu’s architecture seems frozen — or more appropriately, “baked” in time. The distinctive Djingerey Ber Mosque, built of limestone and mud, has been run by Imam Abdramane Essayouti’s family for generations. Islam is thought to have come to this region in the eighth century.

Imam ABDRAMANE ESSAYOUTI (Through Translator): For us this mosque is our heritage. Imagine, it was built in 1325, handed down to us by our parents. This mosque has been here for 700 years.

DE SAM LAZARO: The 15th-century Sankore Mosque was Timbuktu’s nerve center of intellectual life.

Imam ESSAYOUTI (Through Translator): In summertime, they gave lectures here. You have a circle here — at least 40 or 45 or 50 students.

DE SAM LAZARO: Well before Europe’s Renaissance, students and scholars — as many as 25,000 — came from West and North Africa and the Middle East to study Islamic law, theology, and a range of secular subjects.

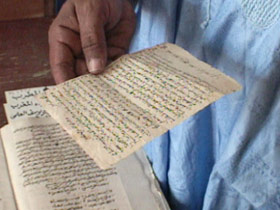

Today, the legacy of that scholarship lies in a vast, scattered collection of historical manuscripts.

ALI OULD SIDI (Guide): Yes, this is the library.

DE SAM LAZARO: The Ahmed Baba collection, named after a 15th-century scholar, with some 40,000 manuscripts.

Arabic was used for theological as well as secular works — testament to the Islamic world’s leadership during the period in medicine and the sciences.

Every now and then, there’s a manuscript in Hebrew. This one is a 16th-century letter by a Jewish trader, writing home to Morocco about market prices in Timbuktu.

ALI OULD SIDI: Timbuktu was really a melting pot where we had Jewish, we had people from North Africa, people from sub-Saharan Africa, and all of them were living in peace here in Timbuktu.

DE SAM LAZARO: So far, only a small fraction of Timbuktu’s one million or so manuscripts has been studied. Stephanie Diakete, a U.S.-born expert on book arts, says the works she’s surveyed are classically Islamic — emphasizing calligraphy — but with distinctive African influence.

STEPHANIE DIAKETE (Specialist on Book Arts): They respect the precepts of Islamic art in that they are geometric based and the use of colors. The drawing is quite close to ethnic art, it’s quite beautiful. The calligraphic style is very specific. It’s quite easy to tell the geographic origin of the scholar by the calligraphy that he uses.

DE SAM LAZARO: Despite a wealth of content, the priority now for scholars and manuscript owners, like Abdel Kader Haidara, is the uphill task of saving the crumbling manuscripts.

Their survival is a tribute to the ancient binders. This Qur’an survived a building collapse. The classic geometric artwork on its goatskin cover is still pristine on the back.

A handful of collections, like Haidara’s, have gotten support from universities and foundations in the West to catalog, conserve, and restore manuscripts.

It’s tedious work and at best involves a small part of the collection. The majority of Timbuktu’s volumes is precariously stored in small family collections.

Abdul Wahid Haidara, who’s not related, has little time. And, on a teacher’s salary of just $50 a month, almost no money to preserve what he calls the family’s heritage.

Haidara has resisted offers from foreign collectors to buy manuscripts, many of which could fetch fortunes in the West. But there’s concern that people struggling to feed their families will be tempted.

Timbuktu’s mayor says the best way to reduce poverty is to attract more tourists — sightseers and scholars — who could both highlight and preserve the historical treasure.

IBRAHIM CISSE (Mayor of Timbuktu) (Through Translator): Timbuktu belongs to all of humanity, not just to the people of Mali. This is a very old learning center, a historical city which has endangered sites declared world heritage by UNESCO. Timbuktu belongs to the whole world and around the world, people should do something to save Timbuktu.

DE SAM LAZARO: There’s not likely to be a renaissance anytime soon. For one thing, the road to Timbuktu hasn’t changed since the city’s heyday in the 1500s. That is, there is no road.

For RELIGION AND ETHICS NEWSWEEKLY, this is Fred de Sam Lazaro in Timbuktu, Mali.