In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Building a Monastery of the Heart

by Judith Valente

“Is there anyone here who yearns for life and desires to see good days?”

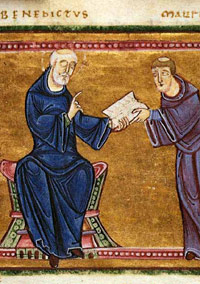

Those stirring words come from one of the most durable spiritual guides of all time, the Rule of St. Benedict. It’s been said everything one needs to know about living the spiritual life is contained in this little book. Over the past year, this 1,500-year-old treatise has become, for me, a constant companion.

Since June of 2008, I’ve had the extraordinary opportunity to spend an average of a week a month at Mount St. Scholastica, a Benedictine monastery for women in Atchison, Kansas. I’ve been invited to share as deeply as a lay person can in the spiritual life of the sisters for a book I’ve been asked to write. I admit I questioned at first what practical wisdom a monastery might hold for a modern, married, professional woman like me. It turns out I’ve learned plenty.

I used to think of monasteries as outmoded remnants of a past era. But now, when I enter Mount St. Scholastica, I feel as if I’m peering into the future, a future our world so desperately needs—one that stresses community over competitiveness, service over self-aggrandizement, quietude over gratuitous talk, and simplicity over constant consumption. The Mount is a place where those who listen are valued as much as those who speak up; a place where people forgo personal wealth but want for nothing, where prayers are said for the victims of violent crime and bells are tolled when a Death Row prisoner is executed.

I identify now with the words of Thomas Merton, the famous Trappist monk and spiritual writer. After his first visit as a young man to the Abbey of Gethsemani, Merton wrote in his journal: “I had wondered what was holding this country together, what has been keeping the universe from cracking in pieces and falling apart. It is this monastery.”

Whenever I walk into Mount St. Scholastica, I have the sense that I’m entering a deeper reality. It starts with the beginning of the day. The sisters don’t wake up and immediately turn on National Public Radio or read The New York Times, as I do. Day begins with Morning Praise. The sisters trace the sign of the cross over their lips and say, “Lord, open my lips, and we shall proclaim your praise.” It’s a way of promising that the entire day is going to be a form of praise. It’s not about checking off all the things on one’s to-do list, or plotting to sell more things today than yesterday or, as in my case, writing more words than I did the day before. It’s about making sure everything we do in the course of the day is an act of praise, an expression of gratitude for life.

After the sisters say that little prayer, they sing. Imagine how different our days might begin, if we started out each morning singing—even just mentally singing something in our head. If you’re someone who loves Broadway show tunes, as I do, you might choose “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning.” Or it could be a favorite hymn (“We Rise Again from Ashes” is one of my morning favorites).

People think of monasteries of very quiet, perhaps even lonely places. But the truth is they teem with activity. The sisters work outside at many different jobs: teaching, doing social work, counseling, and hospital chaplaincy (one at the Mount was even a firefighter, another a funeral director), but everyone also has a job to perform within the monastery. Each sister takes a turn at cleaning the bathrooms and doing the dishes (albeit with industrial-size mechanical dishwashers). Even the prioress and the PhDs have their “at bat” at these menial jobs. It’s a way of saying that all work is sacred. Ora et labora, work and prayer, is the Benedictine motto. I like to think of it not so much as work and prayer, but work as prayer.

“Let the cellarer [the monastery supply clerk] handle the kitchen utensils as if they were the sacred vessels of the altar,” St. Benedict says in the Rule. It’s a reminder to respect the common objects and utensils of our lives and a promise to extend that respect to the people around us, the community we live in, our natural resources, and our environment.

In his book on the Rule of St. Benedict (Always We Begin Again: The Benedictine Way of Living, Morehouse Publishing, 1996) John McQuiston, a trial attorney, points out, “Everything we have is on loan. Our homes, businesses, rivers, closest relationships, bodies, and experiences, everything we have is ours in trust and must be returned at the end of our use of it.” This is the way of monastics. As we continue to reap the damages of our throw-away society, we can see just how far-sighted monasteries have been.

There are some old monastic customs that the sisters don’t follow anymore, and frankly I wish some of them could become a part of our everyday lives. My friend, Sister Thomasita Homan, told me that for many years, whenever a group of sisters were assigned to work together a project, they would bow to each other and say in German (the native language of the first Benedictines in Atchison), “Have patience with me.” Imagine doing that in today’s workplace! I think about how much more pleasant it might be, when I’m out reporting a story for PBS, if I bowed to the cameraman, bowed to the producer, and they to me, and we asked each other to have patience, please, with each others’ human frailties.

Such humility forms the core of monastic life. It is especially important for Benedictines, who take a vow of stability. The vow commits them to live—and grow—with the same group of people at the same monastery for the rest of their lives. Stability recognizes, as one sister put it, that “there’s nowhere else but here.”

At Mount St. Scholastica, there are sisters who have lived together for as many as 75 years. Having moved from state to state here in the U.S. and lived in three European cities over the course of my career, the notion of spending one’s entire life in the same place seems quite foreign to me. In fact, the whole concept is alien to our highly mobile American society. Stability reminds us to grow where we’re planted. A monk was asked, “What is it then to be stable?” And he answered, “You will find stability at the moment when you discover that God is everywhere; that you do not need to seek God elsewhere. God is here, and it is useless to seek God elsewhere, because it is not God that is absent from us. It is we who are absent from God.”

Often that absence stems from a simple lack of balance. We have an abundance of food in this country, plenty of gadgets and opportunities for recreation. What we lack is time to enjoy them. The rhythm of monastic life opens the way for balance. Benedict in his Rule stipulates that monks get seven hours rest a night. Those who require more food because they are ill or weak should get it, and those who aren’t strong enough to do physical labor won’t be forced to do it. The Benedictines even go so far as to call leisure “holy.”

I saw firsthand the Benedictine way of balance when I was at Mount St. Scholastica as Lent began this year. First, the sisters enjoyed the monastic version of Mardi Gras. All of them, even the elderly ones living in the nursing home wing, gathered for beignets and hot chocolate. Not just any hot chocolate, but hot chocolate spiked with peppermint schnapps. The sisters laughed and joked and were having a grand time. But at the appointed moment, everyone got up from their tables and walked in a procession from the community room to the dining room. There, a fire blazed in the fireplace. One of the sisters carried in the palms from last year’s Palm Sunday. One by one she threw the branches in the fire to create the ashes for this year’s Ash Wednesday, and from that moment on there was complete silence in the monastery for the rest of the night and all day Ash Wednesday. A time for fun and leisure, yes, and a time to be serious and prayerful. Balance.

Perhaps the most important word I’ve learned at the monastery is a Latin word: conversatio. It refers to another one of the vows taken specifically by Benedictine monks and sisters: conversatio morum, literally “conversion of morals.” The phrase is often loosely translated as “conversion of life.” But I like the definition Sister Thomasita once gave to me: conversatio as a constant “turning toward,” a constant conversation with life.

I like the idea of turning because it connotes change, and there are certain aspects of my life I’ve been trying to change for a long time. Like my quick temper. I find that I like the person I am at the monastery much better than the person I am in my everyday life, because when I’m at the monastery I’m calm. I’m patient. I don’t lose my temper. Once, just a few days after I returned home from the monastery, I argued with my beautiful husband. It was a totally silly, unnecessary argument, and I emailed Sister Thomasita and asked, “Why do I have these stupid arguments with my husband, who’s the person as close to me as God? Why can’t I live conversatio in my day-to-day life with the people I’m closest to? And she answered, “You are living conversatio. Your struggle. That’s the conversatio.” And that gave me hope—hope that I don’t have to be a saint. I just have to be human.

“Keep death before you daily,” Benedict says in the Rule. It’s a potent reminder not to spend my life twisting in anger or caught up with what Thomas Merton called “useless care.” My stays at the monastery propel me every day to remember what is essential, what gives my life meaning. Merton referred to it as finding “the hidden ground of our being,” finding that place where we not only discover God, but where God can discover us.

I suppose I am just one of the many Benedict has spoken to through the ages who yearns for life and desires to see good days. “Run, then,” Benedict reminds me and all of us, “while you have the light of life, that the darkness of death may not overtake you.”

Judith Valente, a contributing correspondent for Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly, is also a poet and co-editor with Charles Reynard of Twenty Poems to Nourish Your Soul (Loyola Press, 2005).