In This Episode << SLIDE LEFT TO SEE ADDITIONAL SEGMENTS

Harvey Cox Extended Interview

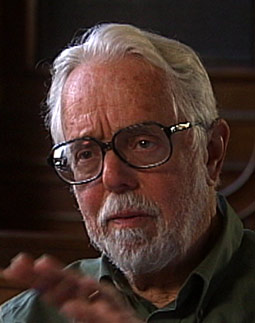

Read more of Bob Abernethy’s September 15, 2009 interview in Cambridge, Massachusetts with theologian Harvey Cox:

Q: Let me begin by inviting you to sum up, if you would, the central idea of The Future of Faith.

A: Let’s say it’s a tripartite thesis in this book. One is that the resurgence of religion around the world and the various religious traditions, which is unexpected, global—there were people who were predicting the marginalization and even disappearance of religion in my early years as a teacher. That disappearance, marginalization, didn’t happen, and in various religious traditions, almost all of them, there’s been a resurgence for complicated reasons. I do not think that is a mere transient phenomenon. I think it’s a basic change in the nature of our civilization, that it will continue, and so, therefore, programs like this one probably have a future. You deal with religion and ethics. The second part of the thesis, however, is that fundamentalisms, I use the word in the plural, which have often been associated with this resurgence of religion, at least in the popular mind, are on the decline. I do not think that they’re going to last out much longer. It’s a recent phenomenon, began in the early 20th century and has appeared in various different religious traditions, always as a kind of a reaction against something that’s going on in that tradition. They claim to be very traditional, but they’re not. It’s really a modern movement, and I think there’s evidence that, in every one of the religions, they are on the decline. The third part of the thesis, and I think it’s one of the most important, not the central part, is that we’re seeing a change in what I call the nature of religiousness, that what it means to be a religious person, or frequently now people will say a spiritual person, they have some questions, occasionally, or often, about the word “religion.” We’re seeing a fundamental change there so that it means something now different than it did 50 or 100 years ago, to say nothing of 500 years ago. And that’s the main thesis of the book. It’s a a mixture of some of the things we’re talking about here as well as some autobiographical illustrations—my experience with liberation theologians, my experience with Pentecostals, with the Catholic Church, in fact with the present pope, and also my early years of formation in a Baptist evangelical congregation. I think it’s important when people are reading about issues as important as this that they know something about where I’m coming from when I’m saying these things and what life experiences have led me to make the kind of statements that I have here.

Q: So how is it changing? Tell me what the elements are of this new thing that you see.

Q: So how is it changing? Tell me what the elements are of this new thing that you see.

A: For Christianity, in particular, to single it out among the various world religions, there’s a movement away from a more belief-and-doctrinal formulation of religion into a more experiential, practical, you might even say pragmatic understanding: How do I get through the day? How do I get through my life? What resources do I have—spiritual resources? There’s a very distinct move in that direction away, from hierarchical kinds of structures in religion toward a more egalitarian form of religious organization. I think the major evidence for that is the enormously new and important role that women are playing which they didn’t play 50 years ago, and there are other evidences for this egalitarian tendency.

Q: Let me take you back to the emphasis on faith and the movement of the spirit and the presence of the spirit in people’s lives, or the hope for it, and contrast that to 1,500 years in which beliefs and doctrines were primary.

A: I contend in this book that for roughly the first 300 years, early Christianity was a faith movement. They didn’t have creeds until the early fourth century, until Constantine. They didn’t have hierarchies. There was enormous variety of different expressions of Christianity which we’re now uncovering, with the different scrolls that are found, have been there all that time. Then, around the early fourth century, with Constantine in particular, there was a massive movement toward hierarchy, a clerical elite, and a creed. Now remember that the creed was insisted upon by the emperor. Not by the bishops, not by the pope. He wanted a creed so he had a uniform expression of Christianity as an imperial project. He wanted something that would bring the empire together. Now it didn’t work that well for him. Nonetheless, I think the creedal understanding, that is, the rather doctrinal and hierarchical understanding, goes back to that very, very unfortunate term under Constantine, which then set the pattern for the next centuries. Now we’re in a new phase in which that is no longer the case, a third phase.

Q: Define for me, if you would, just what are the principle components of this turn toward emphasis on faith?

A: I call it an age of the spirit, with the age of faith in those early years, and then the age of belief, and now this movement toward an age of the spirit, because the spirit indicates, at least in Christian history, the personal, communal, even subjective element as opposed to the hierarchical and doctrinal element in Christianity, and that’s where everything is moving, I think, clearly. The fastest growing movement in Christianity today is the Pentecostal charismatic expression of Christianity—vast variety of them. Nonetheless, what they have in common is an enormous emphasis on community and spirit and experience, and that’s drawing a lot of people away from these previous forms.

Q: Why do you think that is? I mean, why is there this emphasis on the spirit now, as opposed to creeds and beliefs?

A: Well, I think that, given the fact that we are often deprived, in modern technical society, of very much chance for deep, personal experience—we pass each other by in elevators—the yearning for some kind of personal experience, even the yearning for some kind of let’s call it an ecstatic encounter with God or with the divine is there, and the Pentecostals offer this, and they offer it in a community where people support and take care of each other, where there’s also healing. A lot of people are drawn in by the healing. So I think it combines elements that have an enormous appeal. It has no hierarchies. That’s why it branches out in so many different directions.

Q: But you have said that this is not just among Pentecostals, that this movement of the spirit, this emphasis on the spirit, is very broad.

A: It is very broad. I think in the mainline Protestant churches and the Catholic Church the emphasis on community and experience, and also the language of the spirit—and one of the favorite ways for women theologians and ministers now to refer to God is using the language of spirit, because the traditional language of the sovereign God and so on seems, and is, rather hierarchical and masculine.

Q: People have said when they’re referring to this experiential part of the heart it is often described as the heart versus the head—that for a religion to be healthy, it has to have both the spirit and some kind of structure, creeds, or beliefs, to hang all the rest of the feelings on.

A: I agree with that completely, and I think what we’re seeing now is a compensation for centuries in which the main emphasis was on doctrinal assent, hierarchical control suspicious of laity and lay movements, and now we’re seeing a kind of reaction to that, if you will, which inevitably is going to have to find some balance. I study the Pentecostal movement pretty carefully. The younger Pentecostals now are saying, “Hey, we ought to deal with the head a little bit here, too, you know,” some doctrinal or philosophical basis. So you’re noticing that, and they’ll work on that, as well. But what it is is really a complementary movement.

Q: I was particularly interested in your idea that the so-called apostolic succession after Jesus wasn’t something that right back to his giving the keys of the kingdom to St. Peter, but it was something that was created by human beings some centuries later, and I’m wondering if you could describe how that happened and then tell me, particularly, how you think that affects the authority of the Catholic Church.

A: Well, I think the evidence is now in that the whole idea of apostolic authority, apostolic succession, came in much later, let’s say in the 200s and 300s, when Christianity was growing and people were looking around for some way to assert, especially the early bishops, their own authority, and you can see this emerging. The bishops would say, “Well, I go back to Matthew” or “I go back to Peter,” and they would even construct or write gospels and statements that were really—we would call them forgeries. They didn’t have that term in those days. And the interesting thing now is we’re beginning to find these things. You know, that whole stash of documents in Nag Hammadi, the Gospel of Judas, the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Peter, and all those things, which are late. They’re not early. They’re not the apostles doing that. But it was an invention. It was an invention to secure the authority of the church leaders who needed to have some kind of historical backing. I think it means a rather serious rethinking of the basis on which churches that claim the apostolic authority continue to assert their authority. Now, whether they are going to do that or not is another whole question. But when you find out that the historical basis for this is a little shaky, does that affect the way you exercise authority today? I think it should.

Q: Not only how you exercise it, but how the rest of us look at it. Does the scholarship you refer to undermine the authority of the Catholic Church?

A: Well, yes. I think it does. You know, there was a document around just about the time of the Renaissance called the Donation of Constantine. You may have heard of it, and it was supposed to be a document by which Constantine gave a lot of the property in central Italy to the church, and they used that to claim the church’s sovereignty over that. It was proven to be a forgery, and the Catholic Church made the adjustment, and eventually they gave up, many years later, secular sovereignty over central Italy and in some ways the moral authority of the pope became greater after he didn’t also have to be a secular sovereign. I think the Catholic Church can adjust to this quite well, and maybe it’s a very good thing that they have this coming. Now, I don’t know. I’ll be interested to watch, but they have to deal with the fact that the early historical grounding for apostolic succession is really no longer held by most scholars.

Q: In 1965, you published a book called The Secular City in which you thought that the role of religion in modern city life was becoming pretty less important than it had been, and some people said you were wrong about that assertion.

A: The original title of that book was God in the Secular City. Most people don’t know that, and the thesis of the book was the decline of institutional religion should not be viewed as a catastrophe, because God is not just present in religious institutions. God is present in all of creation, in other kinds of movements and institutions and to be discerned, presence of God to be discerned there and responded to. The publisher said no “God in the Secular.” It’s too complicated. Let’s just call it The Secular City. So I’ve lived with that title now for—that was 44 years ago, and I have learned a few things since then. I wouldn’t swear by every sentence in that book. Nonetheless, the central thesis of the presence of God in all of creation and historical institutions, culture, and politics and family I would certainly hold to enthusiastically and say that what I say in this book is the decline of creedal Christianity and hierarchical Christianity is also not a catastrophe. Maybe it points to a really important renewal of facets of Christianity that have been repressed over many, many years. I think it does.

Q: What are the implications of an age of the spirit for everybody who’s religious?

A: Well, I think it means, among other things, that we’ll be seeing, and should be welcoming and affirming, a much wider range of expressions of Christianity. I’ve often been thought of as normative over these 1,500 years of what I call Constantinian Christianity. We see it happening frequently, now, all around the world, especially since Christianity is no longer a western religion. That’s a central and important change in the composition of the Christian world—dates back to only about 20, 25 years. The majority of Christians in the world are no longer in the old steer of Christendom in which Constantinianism was the rule. So we see all kinds of very interesting new theological and liturgical and ethical movements emerging, often around what we used to think of as the periphery. But it’s not the periphery anymore.

Q: And what are the implications of that for the influence of religious life?

A: Oh, I think the influence of religious life is continuing. Not necessarily institutional, hierarchical religious life, but the influence of people who are religiously informed and inspired and supported in communities, working in various kinds of even nonreligious structures and movements. I think that’s on the increase and will continue to be.

Q: The spread of this kind of emotional Christianity throughout the southern part of the world—what do you think that implies for the future of Christian practice in the United States?

A: You know, the term “emotional” doesn’t quite do it. I would prefer personal, experiential. Emotion is part of that, but the experience of community and hope and of affirmation is part of it, too, but they are experiences. I think it’s already having its impact. Somebody has talked recently about the reverse missionary movement of Christians coming from South America, or especially Korea, into the United States and influencing American—or Africa, most recently, African religious movements coming in and influencing American Christianity. I think that’s really going to be a big development in the future.

Q: Influencing it in what ways?

A: Well, toward a more communal and more experiential direction, largely. There may be other influences as well, but I think that’s mainly the way it will influence.

Q: In your teaching and writing career, you’ve been well known as someone wit an uncanny ability to spot new developments in religious life. One of them, certainly, was liberation theology.

A: Liberation theology emerged in Latin America as a way of understanding Christianity, a new way of understanding it from the perspective of those who had been excluded and not part of the clerical elite or the theological elite. They talked about the preferential option for the poor—not just doing something for the poor, but helping the poor to understand the claims they can make on the basis of the gospel. I have a chapter in the book on that as illustrative, precisely of this movement away from the control of hierarchies and creeds, because the basic structure of liberation theology, or what they call the ecclesial base communities, small groups of people, tens of thousands of them, all over Latin America and in other places, getting together, sharing, reading, sharing food, singing, studying biblical texts and thinking about how that would apply in their own lives, and it made, and continues to make, a very significant impact not just on that continent and not just among Catholics. It’s going strong, especially among people who had their first experience within these base communities and are now in other kinds of institutions, especially political, and journalism and education and things like that. That’s where its impact is being felt at this point.

Q: We talked about Pentecostalism a little bit. What are the real implications of that for us?

A: The most important development in the world Pentecostal movement is a movement toward social ministries. They didn’t used to be interested in that in their early years. They were really very much fixed on “my own experience” and, really, getting to heaven. There’s a recent book on Pentecostalism in which the author has coined the term progressive Pentecostalism. They went around and studied congregations all over the world, especially in the nonwestern world, and found that the ones that were involved in community service, in clinics, in hospitals and schools and all of that mainly were Pentecostal and charismatic churches. And they said this is the major trend now. This is what’s happening. So this combination of social ministry and experiential worship is a dynamite combination, and I think that is really going to be influential on North American and, eventually, even European Christianity, which, we all know, needs kind of an injection of life at this point, and it could happen there as well.

Q: Why did the mainline Protestants suffer such a decline over the last 20, 30 years?

A: Well, I think one of the reasons is the mainline churches did allow themselves to drift toward a more hierarchical, less communitarian structure—away from where they were, let’s say, 50 years ago. People need to have a sense of belonging, and that wasn’t there. It was a little bit too audience-oriented: There’s the pulpit there, and here’s the congregation and a choir performing for—now the Pentecostals: everybody sings. Everybody testifies. Jimmy Durante used to say, “Everybody gets into the act,” and it’s richly participatory—if you want to be a participant.

Q: I’ve heard it argued that they became too intellectual and not enough spirit.

A: I think that’s another way of saying the same thing. The clergy—and I take some responsibility for this, having been involved in it for over 40 years—was trained in Christian thought, Christian philosophy, Christian theology, how you deal with the problem of the modern world and all of this, you know, and not enough in how to nurture the experience of God, the experience of the spirit and encounter with Christ, and so the churches which have brought that back in, I think, are finding that it appeals to people.

Q: And what about the place today of what we call the religious right?

A: By religious right I think of a particular political expression of conservative evangelical Christianity, and I think that movement, if it indeed ever was a movement, is now divided and declining in many ways. The agenda used to be driven by Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson and a couple other people. That whole generation is now either dead or really gone, in one way or another, and you have a whole variety of people now in the evangelical community, and they have a political agenda which is far more diverse. I mean, you think of the evangelicals for ecological causes, or the ones who got together to sign the petition against torture, and the opposition to the war in Iraq, where a lot of evangelicals became involved. I don’t consider that a religious right. I consider that religious involvement in the public sphere, which they ought to be doing. I mean, as Christians and as citizens, you ought to be involved. But I think the last couple of presidential elections and by-elections have exposed the religious right as really kind of being, in part, a paper tiger. They just didn’t produce the votes. They were really kind of angry—the fact that they didn’t get a Republican nominee that suited their profile. And I think they’re in considerable disarray, and frankly I’m not mourning over that.

Q: Let me ask you to look around the country and size up what you see going on there. A lot of people think that there’s been a rise of selfishness that perhaps was of basic reason for what happened to Wall Street, what happened with sub-prime mortgages and in other parts of life. What do you see as the problems in this society right now? We’ll get to religion’s role. What’s wrong?

A: It’s the best of times and the worst of times, I think, and I’ll explain that in a minute. But there is no doubt that a rampant culture of market and consumer values really has a grip on many people in America, and therefore accumulating, getting things, getting ahead is for many kind of a principle life goal. I’m told we work harder in America than any country in the world. Productivity is up. But everybody seems to be driven by, especially, the lure of advertising, which says, “You ought to have this. You really need this. You owe it to yourself to have this and that,” and therefore mounting credit card debt, and these people who buy houses on mortgages that they’re not going to be able to afford. I think the role of religion at this point is to make very clear that this structure of values, of consumer values is not coherent with Christianity, with the gospel, with the life and example of Jesus. That’s not what he was talking about at all, so we in the religious community need to take a much more critical, even confrontational, role about this, I think, than we have in the past. There have been moments in the history of American Christianity in which there has been a more confrontational role between Christian values and the values of consumer society. Reinhold Niebuhr, one of my great teachers, was really a great spokesman for that, But that seems to have faded out as the churches have largely simply adjusted to this, even taken over some of those kinds of advertising techniques and consumerist values. But I think we have to get tougher about that and really remind people that this is not what we mean by a Christian way of living.

Q: There is what’s called a prosperity gospel, and lots of ministers preach that God will reward you with everything you want.

A: Yeah. Can you imagine that kind of sermon coming from the mouth of Jesus himself? No. I mean, it’s a rank contradiction, the prosperity gospel. When Jesus says blessed are those who serve and have compassion on the poor, beware of riches, it’s very hard to get into the kingdom of God—passage after passage. It’s right there. You don’t have to look very far for it. The contrast is quite stark, and yet you’re right. There are ministers and preachers who pick up on this prosperity gospel, promise this to people, and I think it’s really, let’s call it by its name, it’s a heresy and needs to be pointed out as such.

Q: You spoke about religious leaders needing to stand up to consumerism. What do you want the churches to do?

A: Well, I think it does start with the ministers and priests in the pulpit, with the congregations, and then I think churches have to speak publicly, and some of them have, about the dangers to the soul of consumerist values, the lethal danger that the accumulationist light poses for you spiritually. There has to be more of that, which is really quite the opposite of the prosperity gospel. I said this is the best of times and the worst of times. I notice increasingly among my students, both undergraduates and students in the divinity school, a deep suspicion of this life of accumulating, consuming, and a realization that a truly spiritual life is going to be more simple and more oriented toward building community rather than competition with the other guy to see who gets ahead. It’s a canard about all young people, that they’re all “me first,” “I first” oriented. I don’t think that’s true. There are many who are. But let me tell you that the urge to graduate from college, like this one, and immediately go down to a Wall Street investment firm is greatly shrunken this year from what it was last year. We’re learning something from this—that this is not only economically, but spiritually a dangerous way to think of your life. I think there’s real hope in a younger generation coming along with that viewpoint.

Q: You’ve been teaching here for 44 years, since ’65. You’ve seen a lot, you’ve written a lot, you’ve studied a lot, you’ve taught a lot. What are the most important things you’ve learned?

A: I have learned how to think about Christianity as one of the possible symbolic ways to approach reality, among others. I used to think of other world religions as kind of exotic, and they’re out there, and they’re kind of curiosities. Now I have made a big adjustment, I think, in my life, and many people are, to say this is the way we see it. Other people see it other ways. This doesn’t invalidate, at all, our way of understanding reality. Rather, we have to look for the common threads, common values, and with these other folks, with Hindus or Buddhists or Muslims, even secular people. That is how to live with radical pluralism. The other big change that I’ve seen is the enormous growth in the hunger and interest in religion and spirituality among students at this university. It’s phenomenal. When I first came here, we didn’t even have a religious studies program at Harvard College. Didn’t exist. We had a very small divinity school. Since then, we have a religious studies program. We can’t add enough courses to respond to all the interest. Furthermore, if you clocked how many students here, on any given weekend, are worshipping, one way or another either at a church or a synagogue or a mosque or Memorial Church, there are more now than probably in the history of the college—a vast variety of ways of worshipping, and being spiritual, religious. It’s not singular. But—there it is. And I think they’re very interested. It’s intellectual curiosity. It’s also personal quest. And we have a responsibility, I think, to help them with that. I’m talking about the students now. But I think it’s also true in the public at large, maybe especially in the younger cohorts of the public at large.

Q: On this question of being open to the wisdom in lots of other religious traditions: If a Christian says, well, I’m a Christian, but of course that’s just one way among many others, what does that do to that person’s confidence and passion about his own faith?

A: Well, it requires a transitioning. It requires a maturation. I think we all grow up with serving ourselves, the center of the world. Then we learn that there are other centers gradually. Not only do I not think it diminishes the validity or power of the faith, in some ways I think it enriches it. I wrote a book about this some years ago called Many Mansions. You know, Jesus says at one point, “In my father’s house there are many mansions.” I would even argue that the plurality of religions in the world is a check on any one of them, including ours, not to get too pretentious and think that we have the whole truth. One of the most dangerous things in any religion is to identify my understanding of the truth, my take on it, with the truth itself. The truth itself is something out there, it’s absolute, but my take on it is relative. Otherwise, I’m guilty of the sin of pride. I mean, I identify my view with God’s view. God is larger than this. God is much larger than any particular understanding of God.

Q: So I can be just as faithful, I can be just as active. I can be just as convinced of the importance of what I’m doing with my life if I say mine is just one tradition among many others?

A: Some of the most faithful and zealous Christians I’ve run into in the last 20 years traveling around the world are precisely those Christians who are living in India, Korea, China, Indonesia, Africa where they are surrounded by people of other religions. It has not in any way diminished how they feel, or their faith. They believe that they have unique contribution to make. It’s different from these other. But it hasn’t diminished it at all. In fact, in many ways it’s enhanced it. And I have a feeling that’s the way it’s going to go.

Q: You are an American Baptist married to a Jewish woman. You have one son by that marriage, and I think a lot of people would be interested in how you accomplish the religious education of your son when the mother is Jewish and you are Protestant?

A: Well, as you can imagine, my wife, Nina, and I talked about this a lot before we were married. We did not want our marriage to be one of these religion-free zones. She’s a serious, practicing Jewish woman. I’m a serious Christian. And we decided that what we would do was to try to learn about and participate in each other’s traditions to the extent that conscience permits. And so that’s what we’ve done. And we also decided before that I would respect the Jewish custom, and indeed Jewish law, that the child of a Jewish woman is Jewish and should be raised with that understanding of himself or herself. And I said, “Look, I agree with this. I endorse it—on one condition: that I also, maybe mainly me, will be responsible for his religious education and formation.” And I was. When he had his bar mitzvah, she’s the one who sent out the invitations and prepared the reception. I was the one who prepared him in studying his Torah passage, and he gave a wonderful exposition of his Torah passage at the bar mitzvah. Now I have to say that, of course, as the son of a Protestant Christian theologian, he got very interested in Christianity and is, I would say, very sympathetic to it and has studied, at Princeton, early Christianity and some recent thought. He’s interested in the phenomenon of religion at large. But he considers himself Jewish, with this interest in religion in general and Christianity, of course, as his father’s particular way of life. So we think it worked out very satisfactorily. Both of us are quite pleased with the way it’s gone. And when I am asked by people about this, “What would you have done if you were Jewish and you’re marrying a non-Jewish woman?” I don’t know. That’s a theoretical question, because the child would not then, by Jewish custom and law, have been Jewish. That would have to be negotiated otherwise. But that’s the way we did it and are continuing to do it. We mark the Sabbath every week, with the lighting of candles and prayers. I go to the Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur. She comes with me to various Christian festivals, as does Nicholas. We have successfully shared in each other’s spiritual traditions, I think, and it can be done, and it’s also very enriching. I mean, I really believe that I understand Christianity better for having participated in Jewish life—and remember, Jesus was a rabbi—than I would have if I hadn’t done that.

Q: How do you pray? What are your practices? How do you attend to these things through the day?

A: I start the day with a prayer, just turning the day over to God, thanking God for this day. We have prayers at all of our meals, a mixture of Jewish prayers and Christian prayers, depending on how we feel. We mark the Sabbath. I have told my friends I’m in search of the perfect congregation. I haven’t found it yet. So I’m one of those people who bounces from one congregation to—I’m somewhere every week, but I go back and forth between the Baptist church which I belong to here, and an Episcopal church in our neighborhood, a black Pentecostal church, and sometimes Memorial Church, the university church here, and I get something from all of them. I feel a little guilty that I’m not sort of committing completely to one of them. But that’s how I do it.

Q: You have the reputation of being a pretty staunch liberal theologically and in every way. Is that fair, or has it changed at all over the years?

A: I’m a chastened liberal, as they say, both theologically and politically. I have been greatly enriched in my fairly liberal understanding of Christianity by my evangelical boyhood, by very significant experiences among Catholics, especially liberation theologians, and others, by my experience with Pentecostals. So I’m an unusual kind of liberal in that—maybe that’s what a liberal should be, one who can affirm and learn from a lot of different sources. But I suppose the label is still a useful one, yeah, and not one to be shied away from.

Q: Have you become more committed to that position as the years have gone by?

A: More committed to the position of being open to learning from various sources? Yes, yes, I have. I started early with that, and it’s really kind of a hallmark of who I am. I think you have to be anchored, though, and I’m really pretty anchored in a form of Protestant Free Church Christianity. That’s pretty secure. That allows me, then, to be open to think other things that I can participate in without feeling that I’m floating away. I have something secure as an anchor.