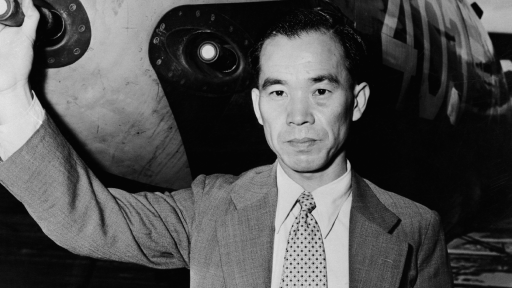

This plane, a Mitsubishi A6M2, better known as the “Zero,” is like the one flown by Saburo Sakai that August day in 1942 when the two engaged each other in the now-famous Dogfight Over Guadalcanal.

While a dogfight can’t be reduced entirely to the distinctions between two machines, it’s necessary to look closely at the aircraft flown by Saburo Sakai and Pug Southerland to understand exactly what may have happened that August day in 1942.

Sakai’s plane, the Mitsubishi A6M2, better known as the “Zero,” was a lightweight, nimble plane with an operating range so long — some 500 to 550 nautical miles — that U.S. Navy analysts consistently overestimated the size of the Imperial Navy’s carrier fleet because they couldn’t find any other way to explain Zero sightings so far from known Japanese land bases. The planes light weight was, at least in part, a result of Japanese manufacturers’ inability to produce powerful engines early in the war. But this limitation forced the Japanese to think very carefully about the design of the plane, and led to some unique and advantageous characteristics.

The plane’s lightweight airframe and skin, made of high-tech duralumin alloy (aluminum alloyed with copper, manganese, and magnesium), gave the Zero its truly remarkable fuel efficiency, operating range, and agility. And the Zero’s armaments were impressive: two 7.7 mm machine guns, along with two 20 mm cannons. Together, the four guns were a deadly combination that gave the pilots multiple options when they engaged.

But the Zero’s engineers — charged with producing the lightest, fastest, most deadly airborne killing machine they could — skimped on some vital gear at the expense of the pilots. The Zero was very lightly armored, and did not have bulletproof glass or the self-sealing fuel tanks that were becoming common on European and U.S. aircraft by WW II.

In addition, the only navigation equipment the planes carried was a compass, and the Zeros were provided with very basic radios, which performed so poorly that many Zero pilots simply discarded them. Two-way radios of the time could weigh as much as 40 pounds — a real burden in a lightweight aircraft; Zero pilots were often forced to communicate with each other by hand signals.

The range and speed of Sakai’s Zero (and a good bit of luck) allowed him to get the best of Pug Southerland in their spectacular dogfight, but had Pug’s guns been working, he would likely have been able to shoot down the flimsy Zero. And shortly after Sakai shot down Pug, the limitations of his airplane were put clearly on display with devastating consequences when he was shot by a tail gunner from an American bomber. The tail gunner’s .30 caliber bullet pierced the Zero’s windshield and went through Sakai’s eye and brain before exiting on the other side of his skull. If his Zero had been equipped with bulletproof glass, Sakai would likely have escaped unharmed.

Wounded and only semi-conscious, Sakai had little chance of surviving. But his skill — and the extreme range of the lightweight Zero — allowed him to fly all the way back to Rabaul with the little fuel he had remaining. Had he been flying any other contemporary fighter, he almost certainly would have perished. To this day, his flight is considered one of the most amazing feats in aviation history, and if not for his trusty Zero, none would ever have heard his account of the famous dogfight.

This Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat is much like the one flown by James “Pug” Southerland on August 7, 1942 when he engaged Saburo Sakai’s Japanese “Zero” fighter plane in aerial combat over the jungles of Guadalcanal.

The Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat piloted by Pug Southerland was a very different aircraft. Aviation historian Barrett Tillman calls it a “broadsword” in comparison to the “rapier”-like Zero. While the heavier Wildcat couldn’t match the Zero’s turning capabilities, climbing speed or range, it made up for its deficiencies with raw power (a 1,200-horsepower engine), superior diving speed, and an amazing ability to withstand punishment.

While the Zero’s designers at Mitsubishi and Nakajima had concentrated on building a purely offensive weapon with little consideration for the pilot’s safety, the heavily armored Wildcat was designed to protect the pilot at all costs. It had a bulletproof windscreen and thick steel reinforcing plates behind the pilot — the armor that had so surprised Saburo Sakai when his blazing machine guns had such little effect on Southerland’s Wildcat during their battle.

The Wildcat was also equipped with a homing device that allowed pilots to find their way back to their carriers or bases in foul weather. And, it had self-sealing fuel tanks, which could take a direct hit without exploding. The tanks were lined with layers of vulcanized rubber that expanded to fill bullet holes. Without the special tanks, Japanese fighters and bombers had a propensity to burst into flames when their tanks were hit, leading Allied anti-aircraft crews to jokingly call the bombers “flying cigars.”

On the offensive end, the Wildcat also had a larger complement of machine guns than its Japanese counterpart — six wing-mounted .50 caliber units. The Wildcat had no heavy artillery like the Zero’s 20 mm cannon, but its six machine guns could be lethally effective, and the pilot did not have to switch between multiple guns that had different rates of fire and ranges.

Southerland’s flying skill and inherent knowledge of his plane’s capabilities allowed him to survive against the quicker Zero. He even managed to gain the advantage, but when he had the chance to shoot down Sakai, his guns remained silent. Southerland, who died in a training accident in 1949, never found out what happened to his guns.

Now, the wreckage of his plane, found deep in a jungle ravine on Guadalcanal in 1998, may reveal why he was unable to finish off the Zero. And it may also answer another lingering question about the events of the dogfight — whether or not Sakai really chose to let Pug live when he shot down his plane. According to his memoir, Sakai aimed for Pug’s engine instead of the cockpit when he came in with his cannons, because he was so impressed by Pug’s flying skills. Some of his other wartime experiences — including his sparing of a transport plane full of civilians over Java and his postwar pacifism — do bear out his claim, but there had been no physical evidence to back up his memoir.

Col. Ralph Wetterhahn, crash site investigator, and Justin Taylan, creator of the Pacific Wreck Database, examine the moss-covered engine of the American Wildcat fighter.

Ralph Wetterhahn’s study of the wreckage — meant to find physical evidence that proves or discounts the pilots’ memories — largely bears out the story as both men remembered it. Examining the Wildcat’s engine, Wetterhahn found clear indications that the rear cylinder had been hit by a large-caliber shell — something very much like the 20 mm shell fired by the Zero’s cannons. The find corroborates what both men said after the battle: Southerland that he had been hit below his left wing root and Sakai that he had aimed for Pug’s engine.

But the mystery of Pug’s silent guns still remains, and unfortunately, the wings of Southerland’s plane had not been well preserved. Only bits and pieces had been found, but amazingly, Edilon Gii, the local man who had first discovered the wreckage, managed to locate several .50 caliber shells from Southerland’s guns. Even after all this time, the shells have a story to tell.

Wettterhahn found that one of the shells displays damage consistent with detonation outside the machine gun’s firing chamber. It has a groove that seems to be the size of a 7.7 mm round — the rounds used by Japanese machine guns — and Wetterhahn suggests that it had exploded in the ammunition belt after being hit by enemy fire. Such an explosion would have jammed the gun and prevented it from firing at Sakai.

The damaged rounds also support Southerland’s report about his encounter with a Japanese Betty bomber prior to his dogfight with Sakai. Pug shot down the bomber, but took fire from the tail gunner. According to Wetterhahn, it’s possible that this exchange may well have left him without working weapons when he engaged the Zeros.

Even after 60 years in the jungle, the wreckage has other stories to tell. As Southerland bailed out of his doomed Wildcat, his sidearm, a .45 automatic, got caught in the cockpit, leaving him weaponless behind enemy lines. Near the plane’s engine, Gii found a rusted pistol. It is impossible to tell for sure whether or not the rusted .45 was in fact Southerland’s weapon, but its make and location at the crash site make it a likely match.

This rusted .45 caliber pistol was found at the site of the wreckage of Sutherland’s Wildcat.

While the story of the dogfight between Sakai in his Zero and Southerland in his Wildcat is an account of a very specific battle between two men, its details are in many ways a microcosm of the much bigger picture of the war in the Pacific. From the planes themselves we can explore not just the engineering techniques of the two nations, but their very different philosophies about how they treated their military personnel, and how they approached war itself.

The Zero — like the Japanese war effort — was conceived under the battle ethic of the Samurai; that is, in terms of powerful and relentless offense. Little thought was given to what a pilot might do if the battle went against him, and as the war went on and Allied pilots learned how to fight against the faster Zeros, the lightly-armored plane became a liability. Not buying into the philosophy of living to fight another day, Japan lost most of its experienced pilots because the Imperial Air Force was ill-equipped to fight a war of attrition in the skies.

On the other hand, The Wildcat — built with an eye toward withstanding punishment before dishing it out — could be looked at as the product of a strategy that began, like the U.S. war in the Pacific, as a defensive effort. Furthermore, unlike Japanese fighter tactics, which were grounded in the one-on-one battle traditions of the Samurai, U.S. tactics were team-based, and depended on the preservation of experienced pilots and cooperation in the air. In fact, Sakai actually made the observation that the American pilots seemed to work in the tradition of American football.

The Zero may have been the more elegant aircraft, but the strategy and tactics embodied by the Wildcat would go on to win the Pacific War. Saburo Sakai’s battle with James “Pug” Southerland ended with a different result, but by pushing themselves and their machines to the limits, they wrote themselves into the history books with one of the most famous dogfights of all time.