When Henry VIII assumed control of the Church in England in the 1530s, he brought to the breaking point ongoing tensions between Europe’s religious and secular leaders.

What, exactly, made possible the translation of the Bible into the language of the common men and women of the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries? How, in a Europe dominated by the Roman Catholic Church, did the Reformation emerge that would question the very foundations of the Church? The answers to those questions are complex, but we can identify a few changes — in political thought, in scholarship, and in technology — that helped make possible the events chronicled in BATTLE FOR THE BIBLE.

POLITICS

When Henry VIII assumed control of the Church in England in the 1530s, he brought to the breaking point ongoing tensions between Europe’s religious and secular leaders that had been going on at least since the leaders of the nation-states of Europe began to consolidate power in the late medieval period, and in many ways since the Church’s establishment in the 4th century.

Though no one living in Europe in the 14th or 15th century would have quite understood our notions of the separation of church and state — there was simply no clear distinction between the two in pre-Reformation Europe — there was certainly ongoing conflict between secular and ecclesiastical authority. While kings certainly appealed to divine right to defend their own authority, the papacy sought to assert its authority in the temporal sphere: imposing taxes, acting as a sort of supreme court in hearing appeals from the courts of the Christian states of Europe, and appointing bishops and priests.

In England, legal maneuvers to assert the precedence of the secular government were proceeding in earnest as early as the mid-14th century. Parliament began to assert English independence in various ways, turning over the power of appointing Church officials within England to the king, following up over the next two centuries with a series of moves against Rome’s authority to collect taxes and decide legal matters. Similar maneuverings took place in France, Spain, Italy, and Germany. Secular leaders in no way questioned the spiritual authority of the Church; rather, they sought to define a separate political sphere.

John Wycliffe became prominent as a negotiator with Rome on behalf of England in the 1360s; before he had publicly stated his reformist opinions on the organization of the Church or the translation of the Bible, he had already thought seriously about the relationship between the Church’s spiritual authority and the authority of secular governments, and had to some degree become suspicious of the Church’s power from a political perspective.

It would, of course, be difficult to say whether Wycliffe’s (or any other reformer’s, for that matter) theological positions had roots in his political experience, but it is clear that he had developed his theories on popular access to the Bible in an era that saw that Church as an institution whose political authority was not unlimited. By the early 16th century, Thomas Cranmer — who was even more embroiled in secular politics — would negotiate the same issues as he brought a new Church into being in an even more fraught environment.

The Renaissance produced an explosion in scholarship and research, as well as a new class of educated laypeople alongside the educated clerics of the Church.

LEARNING AND SOCIETY

As the medieval period waned and what we now refer to as the Renaissance was taking hold in Europe, a major transformation was happening in the minds of Europe. An explosion in scholarship and research was producing a flood of new and rediscovered information, even while a more literate society was evolving, producing a new class of educated laypeople alongside the educated clerics of the Church.

The new merchant economy — the beginnings of modern capitalism — and the new, stronger centralized governments of Europe demanded literate administrators, and by the close of the 15th century dozens of colleges and universities had opened across Northern Europe, joining the traditional centers of Christian education. The universities and the new class of educated laypeople became a strong force in the emergence of “humanism” — the rediscovery of classical texts and the search for authentic original texts to replace what was seen, in retrospect, as mistranslation of important works, including the Bible, by medieval translators.

The influence of increased scholarship is easy to see in the developments traced in BATTLE FOR THE BIBLE. Rediscovery of the original Greek and Hebrew scriptures, largely unknown in Europe since the beginnings of the Church, sparked a wave of new translations of the Old and New Testaments. Desiderius Erasmus, a Dutch humanist thinker, completed a highly influential new translation of the Bible into Latin, based on research into newly rediscovered Greek manuscripts.

Erasmus was certainly no Protestant (and maintained neutrality in the debates between Reformation scholars and representatives of the Church that followed the publication of his work), but saw himself as correcting errors in previous translations and providing a text closer to the intention of the original Church. Still, Erasmus’s translation provided Martin Luther and William Tyndale with the Rosetta Stone they needed — an authoritative text in both the original Greek and the scholarly Latin — to make further translations into the common tongues of the day.

And as these new translations were made available, an increasingly literature-hungry public was emerging to read them, all spurred along by a major advance in communications technology.

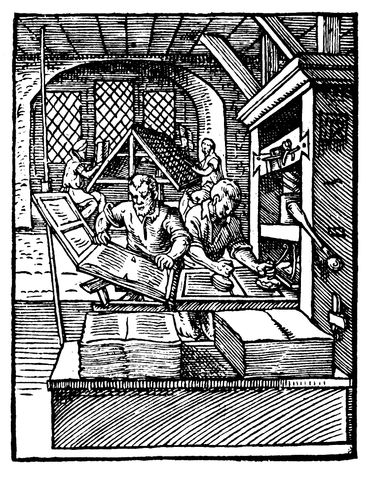

The invention of a commercially viable printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440 transformed the production of books from an academic and monastic pursuit into an industrial activity.

TECHNOLOGY

In 1440, Johannes Gutenberg, a former goldsmith in Mainz, Germany, developed a commercially viable printing press, transforming the production of books from an academic and monastic pursuit into an industrial activity. The impact of Gutenberg’s invention is difficult to comprehend; the effect on European intellectual life can only be compared to the effect of television, and even that comparison cannot capture a transition from a society where the circulation of information was extremely difficult to one in which a more or less free flow of ideas was not just a possibility but a certainty, even given censorship and the threat of death for heretics.

Erasmus’s authoritative edition, and the translations of Luther, Tyndale, and the others across Europe who were working to interpret the original texts, were able to circulate and gain audience in a way that simply was not available to the underground translators of Wycliffe’s time.

Writers and translators were able not only to distribute their work but also to find audiences. Literacy rates were certainly not high in the 15th and 16th centuries (probably 10 percent or less), but a lay educated population had begun to emerge, especially in the urban centers of Northern Europe, and these readers were hungry for books, and not just for officially sanctioned texts. And those who did not themselves read — the emerging urban proletariat, for example — were eager to be read to, in their own languages.

In England, smuggled Protestant Bibles from Antwerp and other publishing and trading centers became best-sellers. (In urban Europe, especially the cities of Germany and the Low Countries, where local governments were powerful enough to operate independently of Catholic Church authority, Protestant communities took hold.) These new texts, easily distributed, reproducible, and portable (Tyndale intentionally sized his edition of the New Testament for personal use, which also made it easy to smuggle alongside the masses of legitimate books being imported into England from the Continent).

These changes in everyday life — in technology, intellectual life, and politics — cannot be said to prefigure Protestantism, but they did set the stage for the massive transformation wrought by the Reformation in the religious life of Europe.