TRANSCRIPT

NARRATOR: Coming up on "Secrets of the Dead"...

I saw what I believed to be the remains of more than one person.

NARRATOR: Hundreds of bones found in a London basement.

MAN: Here was a house that had been occupied by Benjamin Franklin.

NARRATOR: But was Franklin himself responsible for these grisly remains?

Scientists dig into the truth and reveal the dark underbelly of early medicine.

Body snatchers could bring in bodies from the docks, from the graveyards, and into his anatomy school.

NARRATOR: "Ben Franklin’’s Bones" on "Secrets of the Dead."

NARRATOR: A builder digging in a basement in London makes a grisly discovery.

The bones of not one but dozens of bodies.

I was very aware that it could be a major crime scene.

NARRATOR: Benjamin Franklin called this townhouse home for more than 15 years.

What went on at 36 Craven Street, the home of a founding father?

Could it be that Benjamin Franklin was involved with murder?

I mean, we didn’’t know, and we had to find out.

NARRATOR: Benjamin Franklin lived in London at a time when the pursuit of science and the activities of the criminal underworld collided.

They can literally make a killing off the dead.

It was just absolute disgusting.

All that mattered was that the body was dead.

NARRATOR: What does one of America’’s most iconic figures have to do with the bones in the basement?

In December 1997, work was underway at an elegant Georgian townhouse in the heart of London.

36 Craven Street, where Benjamin Franklin lived while representing the American colonies.

In the intervening centuries, countless others have lived there, but now it was undergoing extensive renovation to transform it into a museum dedicated to Franklin’’s life.

But as one of the builders dug into the basement foundation, he made a gruesome discovery.

He unearthed what appeared to be a pit filled with human bones.

He found first one bone, then another and another.

It appeared there were bones belonging not just to one person but several.

Had he unearthed the work of a serial killer?

The police were called.

When I actually looked at the bones, which were in the back of the property, my initial reaction was, "What have we got here?"

I’’ve never seen bones in a house like this before.

I saw what I believed to be the remains of more than one person.

Certainly one skull and a number of major bones of the body.

I spoke to the builders.

They were a little bit shocked.

A little bit apprehensive, one of them was with us.

I would say in my 30 years in the police services, the first private address I’’ve been to where there have been bones found actually concealed in the property, and I thought, "I need to get some expert advice here," and that’’s what we did-- we called on a local coroner to come and give us some assistance.

NARRATOR: It would be the coroner’’s job to determine if foul play had taken place at Craven Street, and if so, when.

Building work was immediately halted and the site shut down.

Coroner Dr. Paul Knapman was called to the house.

[Knocking on door] KNAPMAN: It’’s the duty of a coroner to investigate all violent, unnatural, suspicious deaths and also where the cause of death is unknown.

And this is the actual basement.

Of course, now, I mean, it’’s all nice and clean, but at the time, you must imagine that this is a building site.

We had debris, we had mud and stones and everything like that.

And here’’s the pit.

This is the actual pit.

NARRATOR: Dr. Knapman noticed something intriguing about this macabre collection of bones.

KNAPMAN: These are some of the bones that were actually found.

Here, for example, is a femur, but the curious thing here, it’’s been cut across.

Why is that?

That is not usual.

Similarly, here is a skull, and the skull’’s been cut across there.

I mean, absolutely sawn.

So, it’’s perfectly clear that these have been interfered with.

NARRATOR: The sight of these bones rang alarm bells.

A few years earlier, the story of serial killers Fred and Rosemary West shocked the British public.

The bodies of several women were found buried in the basement and grounds of their home in Gloucestershire.

Between them, the couple was charged with 22 counts of murder.

So, where were we here?

Was this a similar sort of case?

Were we dealing with murder?

NARRATOR: Against this dark backdrop, it was vital to establish the age of the bones.

Test results completely changed the nature of the investigation.

The bones were more than a century old.

Now, if they’’re 100 years old or more, then there’’s no possibility of any living person being charged with a murder or anything like that.

So, to that extent, the coroner isn’’t so involved, and neither are the police.

But these were very unusual circumstances.

I mean, it was a possibility that there had been a murder several hundred years previously.

We didn’’t know, so, we continued to actually try and find out what had happened here.

NARRATOR: Whatever had happened in the basement, it was now a historical case.

And the finger of suspicion pointed to those who lived in the home more than a century ago.

The task of dating the bones more specifically fell to archaeologist Simon Hillson.

He’’s a specialist in the biology and history of human remains.

To perform the tests, he had to go to the basement of Craven Street himself.

It really was quite poorly lit.

There was no lighting, really, in the house, and when I got down there, I saw this hole.

The builders wanted to finish off in the basement in a week’’s time, so, initially, we were given one week to do this small but very complicated excavation.

I was very clear all the time this was an important building, but at that point, I was keeping an open mind just to try and understand what the assemblage was.

NARRATOR: Professor Hillson excavated the site layer by layer, unearthing hundreds of bones.

He also discovered numerous pieces of pottery and glass.

These artifacts would be pivotal.

Carbon dating isn’’t accurate enough for bones that are just a few hundred years old, so, the key was to date these objects.

Tests revealed the fragments were from the mid-1700s, the very time Benjamin Franklin lived at Craven Street.

Could the unthinkable be true?

Could a founding father have had something to do with the pit of bones?

Between 1757 and 1775, Benjamin Franklin lived and worked in the very heart of Georgian London.

He was the first person to represent Pennsylvania and, later, the British colonies of Massachusetts, Georgia, and New Jersey at British Parliament.

Benjamin Franklin was certainly the most famous colonial of his day, and his role here in London was strategic.

NARRATOR: By day, he attended to politics, meeting with the leading figures of the age.

He worked tirelessly during this period to try and effect reconciliation between the interests of the crown and the interests of the colonies.

NARRATOR: But what did Benjamin Franklin do at night?

He threw himself into his other passions of philosophy, science, and invention.

Benjamin Franklin was curious about the world and he operated in it as a gentlemanly scientist.

NARRATOR: After he finally left London in 1775, Franklin went on to become one of the most important figures in history, a founding father of a newly independent America.

But now, almost 250 years after his departure, the discovery of the bones in the basement threatened to sully the great man’’s reputation.

The press began to speculate about crimes carried out at the house.

KNAPMAN: The whole thing was bizarre.

Here was a house that had been occupied by Benjamin Franklin, one of the founding fathers of America, and we’’ve got bones that have been cut across and everything like that.

Could it be that Benjamin Franklin was involved with murder?

I mean, we didn’’t know, and we had to find out.

NARRATOR: But surely a man of Franklin’’s stature could not be implicated.

His early career was spent in Philadelphia, where he established a successful printing business.

In his forties, he turned his attention to his passion for politics and scientific research... and by 1757, had moved to London as a diplomat.

At that time, England was the epicenter of scientific and philosophical advances which captured Franklin’’s imagination.

In 1752, he’’d won worldwide fame when he proved that lightning was not an act of God but in fact electricity.

BALISCIANO: Franklin was passionate about science.

He was intellectually curious and there was no subject that didn’’t pass his attention.

He was here in London pursuing experiments related to electricity.

He looked at better ways to make clocks and improve bifocal lenses.

He even created a flexible steel catheter for his brother.

NARRATOR: And he tried to find a cure for the common cold.

He believed that you needed to let out the stale air and let in the fresh air.

Here in his rooms at Craven Street, he supposedly took an air bath where he sat around without his clothes on for a time each day, and had the windows wide open so that he could take in the fresh air.

Franklin thought that science could really help people, and he was always looking at ways to improve life for himself and for others.

NARRATOR: But what possible connection could Franklin have to the bones?

Could he have been experimenting on corpses for some reason?

Or trying to link the properties of electricity with medicine?

Perhaps the bones themselves could provide clues.

Professor Hillson uncovered more bones which bore the same cut marks the coroner observed.

HILLSON: So, these are some of the leg bones from the site.

There are lots of parts of the limbs.

Most of them have cut marks on them.

These are saw cuts.

You can see the marks of the teeth running across it.

It seems to have been done in one go.

This is the top of an adult skull, and it’’s been cut off using a saw.

We can tell it’’s a saw because of the scratch marks on the teeth, and also it was a straight saw.

It came--they took several cuts.

NARRATOR: One fact was clear-- these bodies had been cut up after death.

HILLSON: All these must be post-mortem, because they haven’’t healed.

If a bone is cut or broken and then heals, then new bone grows over, and so, we can certainly tell if a break took place sometime before death.

NARRATOR: There was an even more unsettling discovery among the bones-- the remains of a newborn baby.

HILLSON: This is from the back of the head, and in a little baby, it’’s made up of 4 different pieces.

NARRATOR: The tiny bones he uncovered made up an almost complete skeleton of an infant.

HILLSON: We really don’’t know who the child was, why it ended up in there.

NARRATOR: Hillson made another discovery-- the human bones were mixed in with animal and bird remains.

This was something different.

This was a jumbled collection, what we call commingled assemblage, and it was clearly different to a regular cemetery.

NARRATOR: The mixture of animal bones included some exotic creatures, like those of a green sea turtle.

HILLSON: These, for example, are the arm bones, the humerus, which are very, very distinctive.

I recognized what I was dealing with the moment I saw them in the ground.

The exciting thing was to find not only the turtle but also mercury sitting in association with it.

It’’s quite strange in an excavation to find something that moves when you’’re trying to dig it up, and I actually had to chase it through the ground with a plastic spoon.

Very strange to see free-flowing, running mercury in the ground during an excavation.

I’’ve never seen it before or since.

NARRATOR: The mercury and the turtle were tantalizing finds.

But for the moment, their significance would remain unresolved.

In total, Professor Hillson unearthed 1,700 animal bones and 2,000 fragments of human bone and teeth.

The remains of an estimated 28 people.

But who was responsible for this grim stash of bones?

Could Ben Franklin have really been involved?

To solve the mystery, the investigation had to eliminate all the occupants of the house at that time.

BALISCIANO: In a sense, the house here at Craven Street functioned as the first de facto American embassy, because Franklin was visited by anyone and everyone calling in from the colonies.

Franklin officially rented 4 rooms in the house, although he was said to be less a lodger than the head of a household living in serene comfort and affection.

He kind of overran the place.

He even had a cat.

NARRATOR: The house belonged to a widow named Margaret Stevenson and her daughter Polly.

With Franklin’’s wife and daughter remaining in Pennsylvania, 36 Craven Street became Franklin’’s home for almost 16 years.

When Franklin came to this house, he was very warmly received and kind of found a surrogate family, similar to what he had left behind in Philadelphia.

His wife Deborah was afraid of crossing the ocean, so it was said, and his daughter Sally remained as well, so, by coming into this house, he was able to have the best of everything, really, because he was in such an exciting place but also had this kind of important private life.

NARRATOR: But it appeared there was another notable resident of 36 Craven Street-- a young doctor named William Hewson also lived at the house.

Was there a connection between him and the pit of bones?

William Hewson had moved from the north of England to London to further his medical career.

10 years after his arrival, while visiting friends on the English coast, he met a woman who would change his life.

William Hewson met a young woman named Polly Stevenson, and she was the daughter of Margaret Stevenson.

Polly was always described as being an unusually intelligent woman, so, Franklin and Polly had a very close relationship.

She was a dear friend of his.

He considered her somewhat of a second daughter.

BALISCIANO: Polly writes a letter to him letting know him that she’’s met someone quite special, and Franklin writes back feigning jealousy, but then goes on to say that he must be someone rather extraordinary if she’’s taken an interest in him.

William and Polly were married at St. Mary Abbots Church on July 17 of 1770, and Franklin actually played a very large role in the ceremony.

He was given the honor of walking Polly down the aisle, and he, at the end, signed their wedding certificate for their marriage.

NARRATOR: Franklin and Hewson were kindred spirits, both swept up by the powerful intellectual principles of the Age of Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment was an age of reason, and trying to be rational about man’’s affairs and understanding the universe, and it celebrated the individual.

NARRATOR: At the heart of this movement was the Royal Society, an influential organization that dated back to the 1600s.

It aimed to develop science for the benefit of humanity.

The great thinkers of the day gathered to demonstrate their work.

This group would provide another tangible link between Franklin and Hewson.

MOORE: We have here the greatest autograph book in the world.

This is the Royal Society’’s charter book.

It contains the founding document of the organization from 1662 and the signatures of all of the Royal Society’’s fellows, the greatest scientists in the world.

You’’ll see here we have the greatest of them all.

This is Sir Isaac Newton.

He was elected in the 1670s and he signed the volume right there.

This page, we have the discoverer of oxygen-- Joseph Priestley.

Very important figure for Enlightenment chemistry.

Here we have the astronomer William Herschel, the man who discovered the planet Uranus and ushered in a whole new era of planetary science.

Most importantly here, we have Benjamin Franklin, the greatest experimental scientist of this period.

These all individuals who made significant impacts on late-18th-century science.

NARRATOR: Then, in 1769, Franklin was one of a group of fellows who proposed a new member should join the society.

On this page, we have the signature of William Hewson.

And it’’s not just Benjamin Franklin who supports him into the fellowship, but it’’s a range of his peers, and really what they’’re saying is here was a man who was a great scientist.

He deserved to be in this book with the rest of science.

And really, when you think about it, this is between these two boards a history of science over 350 years.

NARRATOR: But Hewson was no ordinary physician.

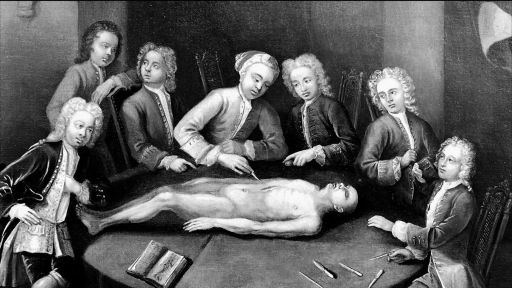

He practiced an art that aimed to investigate the inner workings of the human body by peeling it back, layer by layer.

Hewson was an anatomist.

HEWSON: Hewson entered the scene of anatomy at a really ideal crossroads.

This was a time that they were looking at practical dissections as an art of teaching.

And instead of just researching these things and reading about them, there was much more of a hands-on approach to medicine and science.

NARRATOR: So, did the activities of William Hewson hold the key to the gruesome discovery at Craven Street?

Perhaps the bones were not the result of murders but were in fact anatomy specimens.

The pit of bones held a vital clue.

Hewson conducted extensive research into the human lymphatic system, and his detailed findings were recorded by leading anatomical artists of the day.

But to earn his place in the charter book, he’’d gone a step further, giving a groundbreaking lecture at the Royal Society.

HEWSON: Now, up until this point, it was believed that humans had a lymphatic system.

But Hewson really set out to prove that this existed in other species as well.

NARRATOR: His test subject took everyone by surprise.

It wasn’’t human at all.

It was a green sea turtle.

And one of his most ingenious experiments took place with a dead turtle, and Hewson basically injected mercury into the turtle and watched how it went through the lymphatic system.

NARRATOR: Could the turtle in Hewson’’s experiment be the very same one Professor Hillson discovered in the pit of bones?

HILLSON: This is some of the bones of the shell of the turtle, and one of the fascinating things was there was a little bead of mercury actually resting inside the bone of the shell, and it’’s exciting because it’’s a very clear association with Hewson, the find of mercury in association with the bones of a turtle.

NARRATOR: This was a dramatic turning point in Professor Hillson’’s mission to find the source of the bones at Craven Street.

He now had compelling proof they were the result of William Hewson’’s work.

Could Benjamin Franklin be ruled out as a suspect?

As an anatomist, Hewson was breaking new ground in medical research.

And his work required a vital component-- human corpses to dissect.

But where did they come from?

To answer this question, we must delve into a disturbing world.

A world where those at the very forefront of scientific endeavor in the mid-18th-century rubbed shoulders with London’’s criminal underworld.

Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris is an expert in mid-18th-century medicine and surgery.

People died from all kinds of things in the 18th century that we just don’’t die from today, like smallpox, consumption, typhus, and of course, you could die from really simple things, like a broken leg or a broken arm.

If that leg or arm had to be amputated, you could die of blood loss, you could die of shock, or post-surgical infection.

So, it was a really dangerous time to live.

Medicine wasn’’t hugely advanced, and of course, the understanding of the body was very different than how we understand the body today.

So, for instance, people believed that sickness was caused by an imbalance in humors.

So, you were often bloodlet to cure yourself.

Some of the stranger treatments were electric shock therapy, mesmerism or hypnosis, mercury treatments.

You could be purged, which was very unpleasant as well.

Of course, we know today that probably those treatments did more harm than good.

HEWSON: Hewson was a man of the age, and he was very much involved in pushing the boundaries of modern science and medicine.

This was a time that medicine was becoming much more of a professional science, and it was moving away from more of the medieval quackery that had been previously established.

NARRATOR: But to advance the science of medicine, Hewson had to enter a world that was illegal and unsavory.

Historically, surgery was regarded by physicians as a lowly activity, little more than manual labor.

Its practitioners, unlike physicians who studied medicine, had no formal qualifications.

They were known as barber-surgeons.

So, when you enter a barber shop today, you go in for a shave, you go in for a haircut, but of course, there was a time when barbers did a lot more than that.

They used to pull teeth, they used to pick lice from the hair, they’’d lance boils, and they’’d do some minor surgical procedures.

This really started because monks in the medieval period weren’’t allowed to spill blood, and so the barbers sort of took over from that, and they’’d go into the monasteries and they’’d give the monks haircuts and they’’d also perform these minor surgical procedures.

NARRATOR: If men like Hewson were to elevate surgery from these primitive methods, then they would have to understand the inner workings of the body.

But there was a problem.

Dating back to the era of Henry VIII, only universities and the barber-surgeons were legally sanctioned to dissect bodies.

But in 1745, the barber-surgeons disbanded, providing a new opportunity for ambitions young physicians like Hewson.

At that point, surgery starts to become more professionalized, and the surgeons themselves separate from the barbers and the barbers start to just deal with hair, fingernails, those kinds of things.

NARRATOR: In this new climate, as many as 20 private anatomy schools were set up across London.

And so, what happens is, all these private anatomy schools pop up to give medical students the opportunity to learn anatomy by dissecting their own cadaver.

NARRATOR: However, up until this time, the only bodies legally available to the barber-surgeons had been those of hanged murderers.

FITZHARRIS: People really feared dissection in the 18th century because they had a real literal vision of the resurrection, of the body rising after death, and everything had to be in its place.

So, the idea of being anatomized was really horrible, because your body was dispersed or kept in containers, and it wasn’’t kept all together.

And in fact, you get these really poignant letters of criminals before they die on the scaffold, and they’’re writing letters to their family begging them to come to their execution to claim their bodies lest they fall into the hands of the surgeons and be mangled and torn apart.

And it’’s really awful.

I mean, they actually feared the dissection almost more than they feared the death itself.

NARRATOR: But anatomists needed many more bodies than the gallows could provide.

With no legal means of acquiring them, they were forced to turn to the criminal underworld.

Their pursuit of knowledge would fuel a dark and clandestine profession... body snatching.

Grave robbers assumed a twisted name stolen from the Christian church.

They became known as resurrectionists.

Operating under the cover of night and armed with crowbars and shovels, they scoured graveyards, plundering bodies from freshly dug graves to supply the eager anatomists.

Dr. Simon Chaplin is an expert in the resurrectionists’’ grisly activities.

CHAPLIN: This is Bunhill Field in the center of London, one of the last surviving 18th-century burial grounds.

Today, it’’s surrounded by the hustle and bustle of the city.

In the 18th century, it was far more peaceful and quiet.

It also had the other thing that resurrectionists wanted-- bodies, and lots of them.

Paupers’’ graves, where bodies were laid out in rows-- easy picking for the resurrectionists.

NARRATOR: But the resurrectionists needed to move swiftly.

People really hated dissection.

They hated the idea of it, and they certainly hated the idea of their loved ones being dug up without them knowing and being brought to the dissection table.

Quite often, family members would gather round a graveyard they knew to have been desecrated and if the resurrectionists were caught, they could expect to be hounded by the mob.

FITZHARRIS: You get stories from towns and villages where it would be discovered that a body had been stolen, and all of the relatives would come to the cemetery and dig up the graves of their loved ones and take the coffins home with them until the cemetery could be made secured.

NARRATOR: To make the process as quick as possible, the grave robbers developed specific techniques to get the bodies out of the ground.

Historian Dr. John Troyer has studied their activities.

Using this representation of a grave, he explains the resurrectionists’’ methods.

The grave robbers had a very good system.

It’’s very efficient, it’’s very fast.

They’’d take a shovel, sort of like a spade, and they would cut the grave in half this way, mark it out, and they’’d dig the dirt out from the top half of the grave just to get to the top of the actual coffin.

This part here would be the head of the deceased person.

They were so fast, some of them, they talked about being able to do it in about 8 minutes.

And then they’’d put down the shovel and they’’d pick up some kind of blunt instrument like this, like a pickaxe, and what they would do is they would crack into it.

And then once that was opened, they’’d grab something like this rope.

Sometimes, the rope had a hook on it, but oftentimes they would just loop it, put the rope down in the grave, around the neck of the deceased, and they’’d pull it tight to pull the person out.

NARRATOR: The practice was repugnant, but the law actually governing the stealing of a body was surprising.

CHAPLIN: The truth was in the 18th century, you couldn’’t own a body, and therefore, stealing a body wasn’’t a crime.

Stealing the shroud that the body was wrapped in, stealing the coffin, taking grave goods, trespassing in a graveyard, they were all crimes.

What they wanted was the body itself, so, that’’s what they took.

So, they’’d take off the rings, they’’d take the jewelry, put it back in, cover it with dirt, and they’’d be on their way.

Quite often, no one would be any the wiser as to whether a body had been removed.

The grave would be filled in, smoothed over, made to look good, so, a lot of the body snatching went on without anyone ever knowing about it.

TROYER: You did have to be tough.

You had to be willing to deal with rather gruesome situations, particularly if you cracked open a coffin and the person had been dead for too long, so, it could’’ve been a real-- a decomposing body or a body who died of smallpox.

There could be any number of reasons that it was just absolute disgusting.

NARRATOR: The early anatomists’’ need for bodies drove this underground industry, and it soon became highly profitable.

CHAPLIN: All that mattered to a resurrectionist was that the body was dead.

Child, adult, old, young, diseased, or healthy, it made no difference.

They could sell every body they got to the anatomists.

FITZHARRIS: The body snatchers could literally make a killing off the dead.

They could make as much as 10 guineas per body, which was 20 times the weekly wage of a silk weaver in East End of London.

Certainly there were bodies that were worth more than others.

For instance, if it showed an interesting pathology, if there was a deformity that was very obvious to the body snatchers.

A pregnant woman would fetch a huge amount.

So, body snatchers would be very excited if they came across something that was unusual.

NARRATOR: The industry was as cutthroat as it was lucrative.

I like to think of the body snatchers as the gangs of New York.

They’’re always fighting each other and trying to come up with ways of undermining each other.

If a body snatcher knew that a surgeon was buying from somebody else, he might deliberately try and bring down the authorities on that surgeon rather than the body snatchers.

Dumping a body outside his house, for example, so that it might be discovered by his neighbors and cause a hue and cry.

These were the kinds of tactics that resurrectionists engaged in.

NARRATOR: But as skilled as they were, sometimes the law did catch up with them.

FITZHARRIS: Well, people were certainly prosecuted, but the punishment was relatively low in comparison to how much money could be made.

So, you might end up in jail for a couple months, but during that time, a lot of anatomists also contained to pay the families that the body snatchers left behind.

NARRATOR: These activities seemed far removed from the high ideals of the men of the Enlightenment, like Benjamin Franklin.

So, how did his friend and fellow scientist William Hewson become embroiled in this dark, clandestine world, and what involvement did Franklin himself have?

Hewson came to London to study at the renowned anatomy school of William and John Hunter.

He moved into lodgings at the school and became their apprentice.

His job was to prepare the specimens that would be used for lectures given by William Hunter, one of the most progressive surgeons of the day.

Barts Pathology Museum in London houses some of these 18th-century specimens.

These specimens were typical of what Hewson would’’ve been making as an anatomist, and you have all kinds of wonderful examples of diseases in here.

For instance, you have a human heart, and chances are this person died of a heart attack.

And again, the surgeon wouldn’’t have been able to do anything to prevent this heart attack, necessarily, because they couldn’’t have done internal surgery, but by studying this specimen, they’’d understand the causes of the heart attack.

You also have examples of diseases that people just don’’t die from today.

So, for instance, here you have gallstones.

And of course, people still get gallstones, they get kidney stones, they get urinary stones, but we can remove them a lot more effectively.

But in the past, people died from this all the time, and if you note, the stones are quite large, and that had a lot to do with the 18th-century diet.

NARRATOR: Hewson created thousands of specimens like this for anatomy lectures and lessons.

By stripping away the layers of flesh and muscle to reveal organs, blood vessels, and bones, anatomists came to understand how the body worked.

Hewson wouldn’’t have just had wet specimens in his collection.

He would’’ve had dry specimens as well, and quite a few skeletal remains.

This is a great example of rickets, which was caused by a Vitamin D deficiency, and you can really see the curvature of the bone here.

And having a specimen like this would’’ve taught anatomists about the condition, about the consequences of the Vitamin D deficiency, and it was a very common condition in the 18th and 19th centuries.

NARRATOR: But there was no escaping the unsavory nature of this kind of medical investigation.

This is an example of a dry specimen, and as you can see, the body’’s been shellacked, and it’’s a great teaching tool for the vascular system, but it’’s also the body of a child.

For me, this is a very poignant specimen, because we don’’t know where the child came from.

The child was likely body-snatched.

Of course, the anatomists needed specimens like this to learn about anatomy, but also this was a real person, this was a real child who died, and medicine owes a huge debt to these people who were dissected in the 18th and 19th centuries.

NARRATOR: By 1771, Hewson was making a name for himself as an anatomist.

He was now a fellow of the Royal Society, married to Polly, and a great friend of Benjamin Franklin.

But after 10 years of working alongside William Hunter, the two men had a very public falling-out, forcing Benjamin Franklin to intervene.

He even mediated in a dispute over who owned the preparations, the preserved body parts that Hewson and Hunter had made together.

NARRATOR: Franklin was busy as a diplomat for the American colonies, but he still felt compelled to help his friend resolve this issue.

He wrote many letters back and forth to the two, trying to understand their sides of view.

He ultimately wrote an agreement with the purpose of, you know, preventing this quarrel, but ultimately, it didn’’t work, and the two continued to fight.

NARRATOR: Hewson had had enough, and he and Hunter parted company.

[Ringing] He moved with Polly and their young son into her family home, 36 Craven Street.

Now, without a job, Hewson decided to build his own anatomy theater.

He found the perfect location-- the back of 36 Craven Street.

The house was ideally situated.

Tyburn, the infamous gallows where public hangings were conducted, was just half a mile away.

Hungerford Dock, where dead bodies from ships could be acquired, was just at the end of the street, and a graveyard was located behind the house.

It meant that body snatchers could bring in bodies from the docks, from the workhouses, from the graveyards very efficiently.

[Knocking on door] Could bring them through the back door and into his anatomy school.

NARRATOR: Hewson would give lectures and conduct anatomy classes with the students, but conditions were far from the clinical standards we expect today.

18th-century medical schools were noisome, smelly, messy places.

FITZHARRIS: These bodies would have been in advanced states of decomposition in some cases.

A body literally begins to decompose the moment it dies, and gases build up in the gut.

Things start to liquefy quite quickly.

The other thing is that if a corpse was on the table, until you open up that corpse, you might not realize how advanced the decomposition was until that point.

So, for instance, the anatomist Hewson might open up a body and find that the internal organs had already liquefied and that there’’s really no purpose on going any further with the dissection.

CHAPLIN: The anatomist and his students had to inure themselves to the smell and to the experience of working on these decomposing bodies.

FITZHARRIS: Well, it was William Hunter who said that a person had to have a necessary inhumanity in order to perform dissections and to perform surgeries.

And I think that that really captures exactly what was going on with these medical students.

You did have to overcome something in yourself when you first saw that dead body laid out and you had to cut into it.

NARRATOR: All the remains uncovered by Hillson in the pit bear the marks of dissection, consistent with the work being conducted by Hewson and his students at the Craven Street school.

HILLSON: Taking the top of the skull off is one of the classic things that’’s done at the postmortem.

What happens is they cut straight down through the rest of the skull so the skull is in two halves and students can see the arrangement of all the different bones inside.

The brain would literally have been lifted out, presumably in their hands.

We don’’t have the rest of this particular skull.

I don’’t think we’’ve got any other pieces that match up, so, we don’’t really know whether this was the first thing they did when they made the dissection.

They were supplied with different parts at different times, and it’’s perfectly possible this was just a head.

NARRATOR: But what of Benjamin Franklin?

Did he know the extent of what was happening at Hewson’’s anatomy school?

I think it would be very unlikely that he’’d be unaware.

I mean, just considering the smells alone of being so close to a dissection room.

BALISCIANO: He certainly knew about the anatomy school that was here.

Franklin knew everything that was going on on Craven Street, and he would’’ve been very interested in Hewson’’s experiments.

It must be the case that he knew what was going on.

He was a fellow of the Royal Society.

There were doctors there, there were surgeons there.

He--and he was a man who-- he asked a lot of questions.

He was a polymath, so, he was bound to know.

NARRATOR: But why would such an important figure have condoned not just the gruesome activities but also the lengths to which men like Hewson went to acquire bodies?

It wasn’’t particularly pleasant but it was necessary, and if you wanted to understand people’’s bodies and help in improving the human condition, which is one of the great missions of science, you have to understand things before you can make them better.

CHAPLIN: What comes out in the 18th century are advances in the understanding of anatomy, the structure of the body, understanding physiology, how the body works, and understanding pathology-- what disease looks like in the body.

All of these things contribute to a better understanding of how the body works.

The big difference it makes, of course, is to surgery.

It leads to advances in the practice of surgery, specific operations, but more generally, it breeds a group of surgeons who are confident when it comes to wielding the scalpel, because they’’ve practiced on dead bodies.

When it comes to operating on live patients, they know exactly what they’’re doing.

FITZHARRIS: These are instruments from Hewson’’s period.

They would’’ve been used both for surgery as well as for dissection.

Here you have various amputation knives.

It was really important for them to learn how to do this on dead people, on cadavers in the dissection theater while they’’re not struggling or screaming out in agony or bleeding.

So, you have an example there.

You also have the bone saw.

And one of my favorite instruments in this collection is this tiny, little bone saw, and this would’’ve been used to amputate fingers or toes.

We know that when a surgeon operates on us, when doctor sees us, they’’ve been taught anatomy.

That wasn’’t always true.

It was through the work of people like William Hewson that anatomy as we understand it today came to become part of medical education.

Someone like Franklin would have been appreciative of the kind of knowledge that was being created through dissection and through experiment.

NARRATOR: Hewson himself made significant medical advances.

He discovered the lymphatic system existed not just in humans but also in amphibious creatures and birds.

He isolated fibrinogen as a key protein in the coagulation of blood, and he identified the true shape of red blood cells.

Before this, they had been known as globules, and they were thought to be spherical in nature.

But Hewson used the microscope to look at them and said, "Why, no, they’’re flat and skinny."

So, for all of these amazing accomplishments, Hewson is currently known today as the father of hematology.

NARRATOR: Hewson’’s school provided him with a thriving business to support his growing family.

His classes were very popular, and pupils paid up to 10 guineas for a series of courses.

By 1774, two years after establishing his venture, Franklin’’s friend and protege was considered a great success.

But then tragedy struck.

While dissecting a body, Hewson cut himself.

He developed a fever and fell gravely ill. 5 days later, he called his wife to his bedside and he said, "Take care of our children.

I must bid you farewell."

And then he actually ended up developing septicemia and he passed away on the first of May.

NARRATOR: Hewson was just 34 years old.

It doesn’’t surprise me that Hewson dies this way because there are other examples of anatomists or students dying of septicemia when they cut their hand accidentally during a dissection.

Of course, there’’s no real concept of bacteria or germs at this time.

NARRATOR: Franklin was devastated by the death of this young man, his close friend.

One of the saddest letters that Franklin writes from Craven Street is about the death of William Hewson to his wife Deborah.

MAN AS FRANKLIN: Our family here is in great distress.

Poor Mrs. Hewson lost her husband and Mrs. Stevenson her son-in-law.

He was an excellent man-- ingenious, industrious, useful, and beloved by all that knew him.

She’’s left with two young children and a third soon expected.

He was just established in a profitable, growing business with the best prospects of bringing up his young family advantageously.

They were a happy couple.

All their schemes of life are now overthrown.

I just love this letter because in the first line, it talks about "our family here is in great distress," and this just goes to show how close Franklin was with the Hewsons.

He had a great deal of respect for Hewson and was deeply affected by his death.

NARRATOR: This personal tragedy coincided with a crisis in Franklin’’s political career.

It became clear that reconciliation between Britain and the colonies was not possible.

As he began to understand his countrymen’’s desire for independence, Franklin decided he needed to leave London and return to Philadelphia.

BALISCIANO: I think he does leave London with a very heavy heart.

This was such an exciting place for him to be.

He had great friendships here and he had worked so long to achieve something that, in the end, he couldn’’t make happen.

NARRATOR: Franklin’’s time in London came to an end, but not his relationship with the Craven Street residence.

He left Britain to make history, dedicating his life to establishing America as an independent nation, first as a diplomat in France and later when he returned to Philadelphia.

But despite this crucial work, he didn’’t completely leave Craven Street or the Hewsons behind.

A new chapter began.

After Polly’’s mother passed away in 1783, Benjamin Franklin wrote her a letter and invited her to come to Philadelphia to be his neighbor.

In 1786, Polly decided to move her family to Philadelphia, and there they remained.

Polly became a kind of daughter to him, and so, it’’s only natural that he would want her to be with him in Philadelphia after the end of hostilities.

When Franklin dies in 1790, Polly is in Philadelphia and supposedly comes to his bedside, and all her descendants become American because of Franklin.

NARRATOR: But Franklin’’s legacy went further.

He encouraged Polly and William’’s son to follow in his father’’s footsteps.

Thomas Hewson became a prominent physician.

Now, since William Hewson, there have been 5 more generations of Hewson physicians, and I’’m very proud to say that I am a direct descendant of William and Polly.

I’’m currently in my last year of studying medicine and I’’m very excited to be continuing this legacy within the Hewson family.

NARRATOR: Melissa Hewson and her father Ted have collected information related to the Hewson family history dating back to William and Polly.

TED HEWSON: This marriage certificate between William Hewson and Polly, signed by Benjamin Franklin.

MELISSA HEWSON: Isn’’t that incredible?

And I think that just goes to show how close he was with them during their marriage.

And then these are multiple letters that were written.

This is actually an original letter written in William Hewson’’s writing.

This is an original that was written to Mr. William Hewson.

It says, "Teacher of anatomy at Craven Street."

Now, this was the first edition of Hewson’’s research to be published.

It talks about his research on the blood, the lymphatics.

We were just talking about how he injected mercury into the dead turtle, and this is an illustration of that.

As far as physicians, he was just one of many in the Hewson lineage, from certainly William to Thomas.

Anno.

Anno, Jr. William.

And James.

And Melissa’’s as well, right?

[Laughs] In one year.

And coming--Melissa.

[Laughs] First female.

We’’ll have to expand that frame.

Second redhead.

[Laughs] MELISSA HEWSON: As a small child, I grew up hearing stories from my grandfather about these amazing men of medicine.

Hearing these stories certainly created in me a desire to study in the field of medicine.

And I have to say, when I get married, I don’’t think I’’ll ever be able to change my professional name.

Being called Dr. Hewson on a daily basis will continue to remind me of how truly amazing it is to bear the Hewson name.

NARRATOR: The bones at Craven Street are symbolic of a remarkable chapter in medical history.

The macabre activities of the body snatchers belie the important work that was done to create a profession based on science, logic, and evidence.

The Hewson family just loves the story of the Craven Street bones, and I have to say it’’s the type of story that we tell again and again around the dinner table with friends.

So, it’’s a very unique story to have attached to our name and we just love it.

NARRATOR: But it’’s also provided insight into the life and character of Benjamin Franklin.

MOORE: I think that the Craven Street bone pits are part of Franklin’’s story, yes.

I do think that the material there is a window on a particular time and place and it really says that science was important and necessary.

I think the discovery of the Craven Street bones reveals just how tightly Franklin was enmeshed in the medical and scientific world of 18th-century London.

And it was through that cross-fertilization of ideas, bringing together someone who was an entrepreneur, a philosopher, together with physicians and surgeons that led to such great advances in human knowledge.

We get a kind of 3-for-one deal with Benjamin Franklin House.

We get the incredible character of Benjamin Franklin.

We get a beautiful Grade One simple Georgian building, and we also get the roots of medical history with the Craven Street bones.

NARRATOR: But this is a deeply personal story, too.

It shines a light on the relationship Benjamin Franklin had with the people he considered a second family.

By bringing Polly and her children to live near him in Pennsylvania, Franklin started the Hewson family on a new path in a new country.

MELISSA HEWSON: So, I have to say that every time the Hewson family comes to see Franklin’’s grave, it’’s a very special moment for us.

Our family is just filled with deep emotion of gratitude.

We look at Ben Franklin and we see someone who’’s responsible for bringing us where we are today, and I think that’’s just an incredible history.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪