By Chuck Meide

Director, St. Augustine Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program

Nearly 50 years before Jamestown, St. Augustine was founded in 1565. Secrets of Spanish Florida reveals the forgotten history behind America’s true first permanent European settlement. In this original post for Secrets of the Dead, Archaeologist Chuck Meide provides some historical insight to St. Augustine’s establishment.

“Those Spanish conquistadors might have marched right though our backyard,” my father used to tell me. He was referring to the Spanish soldiers under command of Pedro Menéndez de Aviles, who suffered through a miserable forced march through the swampy wilderness in hurricane conditions. They were on their way from the nascent settlement at St. Augustine to sack the French Fort Caroline. I grew up in the heart of the story, in Atlantic Beach, a suburb of Jacksonville, Florida, south of the St. Johns River which the French had named the River of May in 1562.

“Those Spanish conquistadors might have marched right though our backyard,” my father used to tell me. He was referring to the Spanish soldiers under command of Pedro Menéndez de Aviles, who suffered through a miserable forced march through the swampy wilderness in hurricane conditions. They were on their way from the nascent settlement at St. Augustine to sack the French Fort Caroline. I grew up in the heart of the story, in Atlantic Beach, a suburb of Jacksonville, Florida, south of the St. Johns River which the French had named the River of May in 1562.

It was a great story, a tale of soldiers and galleons fighting storm, shipwreck, and slaughter. It was a story that perhaps inspired me to become an archaeologist. It is the origin story of our nation, the story of the founding of St. Augustine, America’s oldest city. As a child and later a teenager, I regularly visited St. Augustine, reveling in its ancient fortresses, colonial buildings, and brick-paved streets, all steeped in rich history. I remember in class I used to draw French soldiers battling Spanish soldiers, and that I favored the French, a futile attempt to root for the underdog, or perhaps the home team, as Fort Caroline was closer to my backyard. But of course, the story’s ending was inevitable, and it was the Spanish who prevailed. Their triumph was so decisive that it would cement almost two and a half centuries of Spanish rule in Florida and result in the delightful Spanish flavor that draws so many tourists to St. Augustine. As I grew older, I realized that my friends who moved in from outside Florida didn’t know the story of St. Augustine. They didn’t realize that the first settlement was not in Jamestown, and that the first Thanksgiving was not at Plymouth.

A Forgotten History

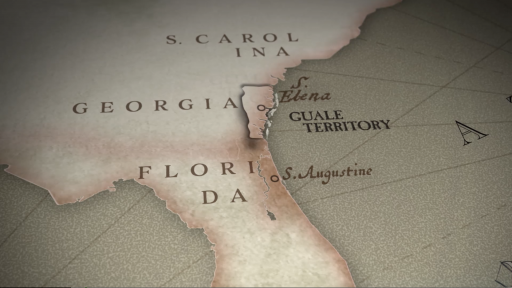

In spring of 1565, King Felipe of Spain had ordered Menéndez to mount an expedition to establish a settlement on the east coast of the vast land known as La Florida, which at the time stretched north to Virginia and west to Mexico. While preparing for the expedition, alarming new intelligence reached the Spanish court—there were interlopers in Spain’s territory. The year before, a French enterprise under command of Rene Laudonnièrre had established a settlement known as Fort Caroline on the River May. Spanish spies in the French court related that the notorious French naval commander Jean Ribault was, at that very moment, preparing a fleet of his own to re-supply the fort. The most outrageous thing was that the French colonists were of the new Protestant sect. Not only were they intruding on His Catholic Majesty’s land, but they were heretics, an affront to God in the eyes of the Spanish.

“They didn’t realize that the first settlement was not in Jamestown,

and that the first Thanksgiving was not at Plymouth.”

Immediately, the nature of Menéndez’ expedition changed, from colonization to conquest. The king ordered Menéndez to drive out the French with “fire and blood” and he increased the number of soldiers on the expedition to 500 (along with 200 sailors and 100 colonists). The Spanish fleet set sail on June 29, only two weeks behind the French. The two fleets raced across the Atlantic. Menéndez was driven to reach Fort Caroline first so as to cut off Ribault’s re-supply fleet from the fort. It is a little-known fact that Ribault and Menéndez had faced each other once before, in a naval battle in the English Channel. In that engagement, the French captain bested the Spaniard. Menéndez was determined to beat the Frenchman this time.

But Ribault won the first round, arriving first in Florida and offloading troops and some supplies by the time Menéndez showed up in his massive galleon San Pelayo. This was on September 4, and Menéndez wasted little time, opening cannon fire on the French galleons at anchor off the river mouth. They cut their anchor lines to make a quick escape, and Menéndez, realizing the precarious nature of his position, sailed to the south to hastily establish a fortified land base of his own. The stage was now set for a remarkably fast-paced endgame.

On September 7, 1565, a Spanish force disembarked at St. Augustine and began digging a temporary defensive entrenchment. The following day, with great ceremony, Menéndez himself came ashore and formally founded St. Augustine. He also decided to only partially unload his storm-damaged galleon, which at 906 tons was too massive to enter the St. Augustine Inlet. After only two days of offloading supplies, he sent his flagship to the safety of the Spanish Caribbean instead of keeping it exposed in a position of danger from French attack. San Pelayo would undergo a mutiny and eventually shipwreck off the coast of Denmark, but that is another story.

Menéndez’ insight proved uncanny. Ribault had decided to launch a preemptive attack, hoping to catch the Spanish while ferrying cargo ashore, and he took two days to prepare. With a decided advantage in numbers of soldiers, Ribault arrived at St. Augustine on the 10th of September with his four largest galleons, and almost succeeded in capturing Menéndez, who was in a smaller vessel and was barely able to make it over St. Augustine’s notorious sandbar. But now that very sandbar protected the Spanish, preventing the large French ships from advancing upon the fledgling settlement. Instead, Ribault’s fleet turned south to pursue the Spanish galleon San Pelayo, which could just be seen on the horizon.

Hurricane Season

That was when the storm struck. It was 452 years to the day whenHurricane Irma would hit St. Augustine in 2017, but by all accounts this storm was massive and significantly more powerful. It drove all of the French ships before it, wrecking them one by one. In this single storm, France’s hope for a New World empire was dashed to pieces, just like her ships in the roaring surf.

Now it was Menéndez’s turn for a bold attack. He knew the French ships would not be able to make their way back north, even if they survived the storm, which was still raging and would continue to do so for days (this weather was reminiscent to 2017, with a hurricane and nor’easter back to back). Leaving a small force to guard St. Augustine, Menéndez and the bulk of his men set out on an overland march through the flooded wetlands between St. Augustine and Fort Caroline on Sept. 18. Conditions were so wretched that his men almost mutinied, but at the dawn of Sept. 20, the Spanish troops arrived at the French fort, which had been left mostly unguarded. With the rain still pouring, the French were caught totally by surprise, and the Spanish breached the walls and took the fort. Around 130 Frenchmen were killed outright, 45 to 60 more (including Laudonnière) escaped, and 50 women, children, and a few men were spared.

Those who escaped the attack led by Laudonnière and Ribault’s son, Jacques, fled for France in their two most seaworthy vessels. They left on Sept. 25, two weeks after Menéndez’ arrival in Florida. Menéndez renamed the fort San Mateo, left a garrison at the site, and returned triumphantly to the settlement in St. Augustine on Sept. 27.

The shipwrecked men from Ribault’s fleet, meanwhile, were cast upon a hostile shore well to the south of St. Augustine, in the vicinity of Cape Canaveral. They had begun the long march northward back to their fort, which unbeknownst to them could no longer provide refuge. They had gathered into two separate groups, the southern one consisting of survivors from Ribault’s flagship La Trinité and the northern group from the other three ships.

“In this single storm, France’s hope for a New World empire was dashed to pieces, just like her ships in the roaring surf.”

The Spanish had been notified by local Indians that French survivors were assembled at the next inlet to the south. Menéndez met this first group on Sept. 29, at what is today called Matanzas Inlet. Once the survivors heard their fort had fallen, they decided to surrender and put themselves at the mercy of Menéndez. He showed little, sparing only a dozen or so and putting as many as 110 to 200 men to the knife.

The second group of survivors, including Ribault himself, arrived on Oct. 11. This time around half of the beleaguered shipwreck survivors refused to surrender and fled into the wilderness. The remainder surrendered and faced a similar fate as the first group. Between 5 and 16 were spared, while between 70 and 150 were killed. Matanzas Inlet, where so many men were murdered, got its name from this event. In Spanish, matanzas means “slaughter.”

With the French threat completely eliminated, Menéndez focused on fortifying St. Augustine and other locations along the coast to consolidate Spain’s claim to Florida. The last of the French survivors who refused surrender disappeared into the wilderness and into history.

The Search for the Lost French Fleet

In the summer of 2014, on the 450th anniversary of the founding of Fort Caroline, I led an archaeological expedition to find the lost French fleet. Sponsored by the St. Augustine Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program, the research arm of the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum, and partnering with NOAA, the National Park Service, the State of Florida, the Institute of Maritime History, and the Center for Historical Archaeology, we spent several weeks conducting an archaeological survey in the waters of Canaveral National Seashore, adjacent to a series of archaeological sites on land identified as French shipwreck survivor camps. Searching for a particular ship after four and a half centuries is like hunting for the proverbial needle in a haystack. While we indeed found a shipwreck, it proved to be a modern shrimp boat!

Since that time, however, a group of treasure hunters have discovered a wreck that appears to be the Trinité off Cape Canaveral. Normally, archaeologists are disappointed when treasure hunters discover and dig a shipwreck, as they eschew the scientific techniques and analyses regularly used by archaeologists, and their work invariably results in an unnecessary loss of historical knowledge. But if this wreck is the Trinité, then, as a French warship, it is recognized by both U.S. and international law as still belonging to France. The case has worked its way into the federal court system, and a court order is currently preventing the treasure hunters from diving on the shipwreck until its ownership is clear. As the evidence that this wreck is the Trinité seems indisputable, I expect that France will be granted ownership of the wreck once a final ruling is issued, and subsequently will sponsor a scientific, archaeological excavation. The historical significance of this vessel, the first shipwreck ever found carrying colonists seeking religious freedom in the New World, is unparalleled, and it will undoubtedly become one of the most important shipwreck excavations of the 21st century.