By Bernadette Murphy

Since I made the TV program “Van Gogh’s Ear” for SECRETS OF THE DEAD, my life has changed pretty much completely. I’ve given public talks at many museums and institutions—the National Gallery in London, for example—been invited to speak at major literary festivals, received a letter from the Van Gogh descendants congratulating me on my hard work, and been recognized many times in the street. It’s all been amazing. I know that the Wikipedia page on Van Gogh was changed more than 600 times and that an animated film about Vincent had to be delayed for a year while they painted 3000 new images in light of my work.

Since I made the TV program “Van Gogh’s Ear” for SECRETS OF THE DEAD, my life has changed pretty much completely. I’ve given public talks at many museums and institutions—the National Gallery in London, for example—been invited to speak at major literary festivals, received a letter from the Van Gogh descendants congratulating me on my hard work, and been recognized many times in the street. It’s all been amazing. I know that the Wikipedia page on Van Gogh was changed more than 600 times and that an animated film about Vincent had to be delayed for a year while they painted 3000 new images in light of my work.

10 things I revealed about Vincent van Gogh

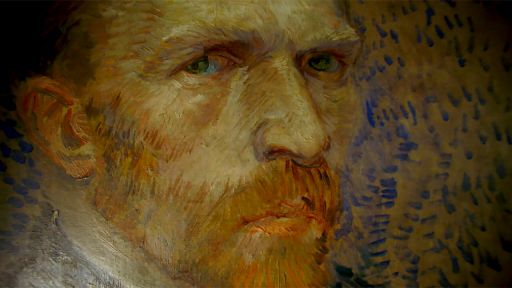

1. What he did to himself on the night of 23 December 1888.

This may not seem important, but for years academics believed what appeared to be ‘eyewitness’ testimony: that of a painter who had visited Van Gogh in the hospital in Arles a few months after the incident. He said that Vincent “cut off the lobe (and not the whole ear).” I didn’t know whether this was true or not, but for various reasons that I explain in the documentary and in my book, Van Gogh’s Ear (published in the USA by Farrar, Straus & Giroux), this didn’t seem to hold water. Then I found a document in a US archive from Dr. Felix Rey—the very doctor -who treated Vincent at the hospital in Arles in 1888. The document had been overlooked by historians as it was in French in an American archive. This was absolute proof that the story was wrong and this document changed history.

2. What’s under the bandage

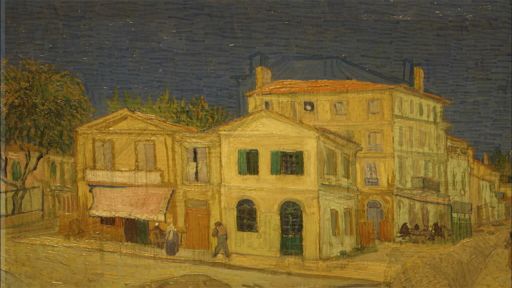

Dr. Rey’s drawing shows that Vincent cut off most of his ear. He cut through an artery and the scene that the police found the next morning would have been of absolute gore, exactly as the artist Paul Gauguin described in his autobiography. The police thought Vincent had been murdered by Gauguin, who had slept in a hotel for the night. When he returned to the Yellow House, he was promptly arrested.

3. How he did it

There had always been confusion as to whether Van Gogh used a knife—as his long-suffering brother Theo maintained—or a cut-throat razor. In the end, the confusion was resolved. A poor translation from Dutch of the word for ‘blade’ and a ‘cut-throat razor’ ended up being translated as a ‘knife.’

Dr. Rey’s drawing shows that Vincent cut most of the ear off using a cut-throat razor, leaving a small piece of the lobe behind. It is very chilling and emotional to see as you look at the small sketch—it is no longer simply the most famous anecdote about Van Gogh; he really did cut off almost all of his ear. It’s brutal and chilling.

4. What treatment he had

The treatment I found through digging in endless archives. Luckily, Vincent received a brandnew treatment—an antiseptic swab called an ‘oil-silk dressing.’ It was a new technique in 1888, as it had only been invented by Joseph Lister a few years before. The application of oil to keep it moist and the bandaging that held it in place—wound tightly under his jaw and across his chest—must have made the dressing extremely uncomfortable. Nonetheless, Van Gogh found himself in the right place at the right time. In late December 1888, Felix Rey was simply a young intern at his first post, yet he was familiar with the most up-to-date techniques. Without Dr. Rey’s intervention and skill, Vincent would almost certainly have died.

5. The identity of ‘Rachel’

No one knew who the mysterious “Rachel” was. I had found her early on in my research. Her real name was Gabrielle. She never left Arles except for one trip to Paris for medical treatment, and perhaps met Vincent there. She was never a prostitute as was once thought—she simply was working as a cleaner at the brothel when on December 23rd, 1888, Vincent turned up with a package for her. Upon opening it, she promptly fainted.

The accepted belief was that, Gabrielle was at the brothel that night so she must have been a prostitute—but this was not the case. All her life she suffered from whispers behind her back. It was impossible to persuade the public she wasn’t a prostitute once people had assumed she was. As the family were so upset about this blight on her character, I promised not to reveal her surname. However, I knew that the clues I gave in the book would mean that someone would follow this up and find out who she was. Her surname came out in late July 2016 via an internet article.

6. Gauguin’s actions that night

Paul Gauguin, the artist, had been sharing a house with Vincent. His part in the story was confusing as he left two accounts—both slightly different—of what happened that night. I explain this in detail and unravel the whole story carefully in the book. Gauguin comes across not as a callow man who left his friend in his hour of need, but as a man completely out of his depth, facing a situation for which he had no life experience: a man in full throes of a complete mental breakdown.

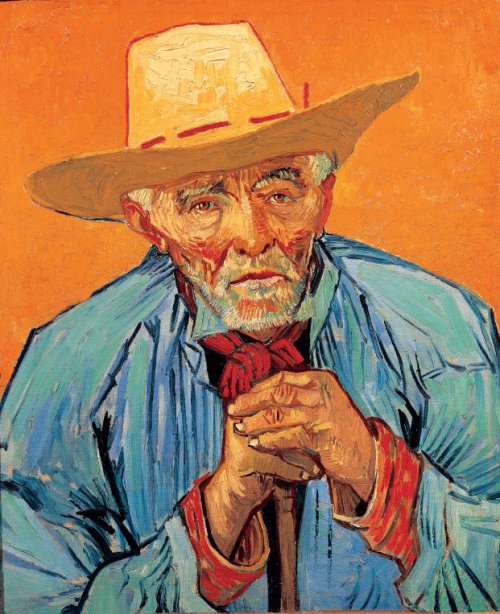

7. The identity of the shepherd ‘Patience Escalier’

This man, a shepherd that Vincent painted was only known as “Patience Escalier”—nothing else was known about him or his life. He has the most amazing face and is one of Vincent’s most famous portraits. Not only was I able to clearly identify him as Casimir ‘Patience’ Escalier (thanks to the database I built up of everyone who had lived in Arles in 1888—which is now almost 16,000 strong), I was also able to find out that he died at the hospital in Arles while Van Gogh was a patient there. They were in the same ward. In fact, in the painting Ward of the Hospital in Arles, he is shown symbolically by the empty armchair which is placed next to Vincent, who is wearing a straw hat and reading a newspaper.

8. The identity of ‘La Mousmé’

She is a very beautiful young girl, painted holding a branch of oleander. Vincent describes her as being around 12. I wondered who she was—after all, who in the late 19th century, would let such a young girl sit for hours on her own, having her portrait painted by an unmarried man? I was also intrigued as she was not wearing traditional costume, which meant she was either a Protestant or from another town. In Arles, Catholic women wore the traditional dress in the 19th century. She also appeared to be wearing a corset, which I though odd for such a young girl. I managed to identify her by contacting all sorts of places to understand whether it was likely for young children to wear stays (indeed it was quite normal in the late 1800s for girls to be placed in corsets prior to puberty), and worked out that she was the niece of Vincent’s cleaning lady. Her name was Thérèse Antoinette Mistral.

9. The identity of his cleaner who inadvertently set off the petition to get Vincent out of Arles

This was hard to work out… yet I felt I had to, as she is an important character in what happened to Vincent Van Gogh after he cut off his ear. She cleaned Vincent’s house several times a week. However, in February 1889, when she noticed that his behavior was again becoming erratic, she mentioned this to her neighbor. The neighbor in question was her cousin who ran the grocery store adjacent to the Yellow House. This series of events led to a petition being mounted to get Van Gogh out of town. This petition and its complaints are always quoted in any discussion of Vincent’s madness. My research found that the petition was never a question of the whole town of Arles being “up in arms against poor Vincent.” Instead, it was signed by a few close friends of the house manager to get the Yellow House back from this rather “strange” tenant.

10. The names of all the people who signed the petition

Vincent thought that 80 people had signed the petition, but in fact only 30 people did—a misconception long exploited by historians to show how mean and petty the Arles people were, and given a completely different spin by my research. It showed that 24 of the petitioners were not even people from Arles. I traced every person by their signature (which took me three solid months), and found out that it was a bunch of cronies who wanted to get Vincent out of his house. They persuaded all their acquaintances to sign the petition, and exaggerated how crazy Vincent was.