Historian Michael Francis’s journey through the documents at Archivo General de Indias

By Michael Francis

December 21, 2017

Archivo General de Indias

It is still dark when Spain’s Archivo General de Indias opens its doors in late December. At this time of the year, morning temperatures in Seville can be chilly, a welcome contrast to the staggering heat of the city’s long summer months. This morning I can see my breath as I begin the 20-minute walk to the archive, winding through narrow streets and quiet plazas lined with orange trees. When I turn the corner at the end of Calle Don Remondo, I catch my first glimpse of St. Mary by the Sea, known to most simply as La Catedral, the world’s largest gothic cathedral and Seville’s most iconic structure. Directly to the south of the Cathedral, bound by Plaza del Triunfo on one side and the towering walls of the Real Alcázar on the other, stands the Archivo General de Indias, or AGI.

Over the past two decades, I have walked this route hundreds of times. The views never get old.

Established in 1785, the AGI’s privileged location is a testament to its value as one of the most important historical archives in the world, one that documents the long imperial history of Spain in the Americas and the Philippines. In 1987, in recognition of the AGI’s global significance UNESCO identified the building and the documents it contains–more than 43,000 legajos (document bundles)-as a World Heritage Site.

For generations of Florida scholars, the task of uncovering the mysteries of Florida’s colonial past began at the AGI. Working here can be both enthralling and frustrating; one could spend decades exploring this remarkable collection and still not read everything related to Spanish Florida.

Over the past ten days, my own research has focused on just one of those 43,000 bundles, a rather thick tome with more than 2,000 pages of documents in it, dating from the period between 1597 and 1602. At first glance, the material might seem rather mundane; there are detailed lists of armaments, ship supplies, construction material, inventories, as well as food and clothing provisions distributed to the city’s residents.

“One could spend decades exploring this remarkable collection and still not read everything related to Spanish Florida.”

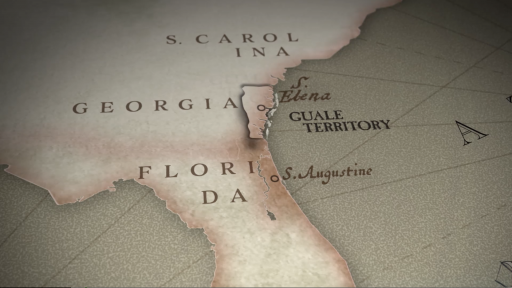

However, a closer reading reveals some remarkable glimpses into daily life in colonial St. Augustine, Spain’s northernmost colony in the Americas. In it, we are introduced to the city’s tailors and shoemakers, its blacksmiths and carpenters, priests and friars, soldiers and sailors, royal officials and royal slaves, as well as dozens of neighboring Indian chiefs who traveled to St. Augustine over that six-year period. Some of those chiefs came to negotiate peace terms or the exchange of captives (which was common throughout the colonial period). Others brought maize to sell, or laborers to serve in the city’s fields or in other projects. In return, Spanish royal officials provided Native rulers with rare luxury items such as clothing, hats, blankets, glass beads, axes, metal tools, and wheat flour. At least one close ally received a horse. Alliances were not free in Spanish Florida, and St. Augustine’s royal officials had no choice but to issue regular payments to Native chiefs. And when payments faltered, so too did alliances. Gifts were of such importance to Spanish-Indian relations in Florida that in 1593 the Crown established a permanent fund, known as the gasto de indios, from which to supply Native elites with luxury items.

This morning, as I read through hundreds of entries recorded by St. Augustine’s treasury officials, one entry in particular captures my attention. It dates to August 22, 1600, and records the purchase of some fabric and thread to be used to design a new dress for a Timucua Indian woman named Doña Ana, the ruler of San Pedro (present-day Cumberland Island, Georgia) and several other neighboring chiefdoms. Doña Ana had recently inherited the chiefdom and this was her first official visit to St. Augustine as San Pedro’s ruler.

To prepare for her visit, St. Augustine’s governor summoned an Irish soldier/merchant named David Glavid, from whom he purchased the fabric needed to tailor Doña Ana’s new dress. The forty-year-old Glavid, who had lived in St. Augustine for just over three years, presented the governor with some of his finest fabrics, including yellow taffeta from China, strips of yellow velvet, and gold and silver thread.

Plaza del Triunfo.

An Irishman in St. Augustine

The real name of the Irishman who procured the material for Doña Ana’s outfit was Darby Glavin, but to the Spanish in St. Augustine, he was known as David Glavid, or at times, Davi Glavi.

One day, I intend to write a book entitled Ten Colonial-Era Floridians I Wish I Could Have Taken to the Pub. David Glavid is one of them. Born in Ireland ca. 1560, little is known of Glavid’s childhood, but by his early 20s, he had established a career as a maritime merchant. In 1584, English corsairs captured Glavid’s ship as it sailed out of Britanny, loaded with wine and other merchandise. The Englishmen seized the cargo, and Glavid was forced to join Richard Grenville’s colonization expedition to Roanoke, where he remained for a year and a half before Francis Drake’s fleet arrived in the summer of 1586 and transported the Roanoke colonists back to England. But Glavid did not remain in England long. Shortly after his arrival, Queen Elizabeth ordered him to return to Roanoke, along with 150 other colonists. But when the two English vessels stopped briefly in Puerto Rico to gather fresh water, Glavid seized the opportunity and escaped. In his testimony recorded more than a decade later, Glavid claimed that he immediately informed Puerto Rico’s Spanish governor of an English plot to attack the island.

“When Glavid first reached St. Augustine, he must have been struck by the town’s diversity.”

It appears that Glavid spent some time serving in the Spanish galleys, but by 1597, he was a free man. In early June of that year, Glavid moved to St. Augustine, where he earned a living as a soldier and a merchant. There, Glavid sold a wide range of goods to St. Augustine’s royal officials, among them a variety of textiles (from course wool to fine silk), felt hats, butcher knives, turpentine, candles, and silk buttons.

When Glavid first reached St. Augustine, he must have been struck by the town’s diversity. A Frenchman named Jean Loconte served as the city’s surgeon and chief physician; the city’s fifer and trumpeter was a German named Jacome Braunel, and more than thirty Portuguese men lived in St. Augustine, along with several Flemish. At least forty royal slaves, both men and women, performed duties critical to the Spanish settlement, laboring in St. Augustine’s fields, building and repairing city buildings, collecting turpentine, and working in the coquina stone quarries. During “tiempos desocupados” (spare time), they wove match cord for the Spanish soldiers.

The single most populous group in the region were the local Timucua, whose ancestors had lived on that same land for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. Throughout the sixteenth century, the Timucua, Guale, Potano, Apalache, Calusa, Xega, Tequesta, Togobaga, and other ethnic groups vastly outnumbered Europeans and Africans in Florida, despite the ravages of disease, migration, violence, and warfare.

David Glavid was one of at least two Irish residents in St. Augustine. The other, a man named Ricardo Artur (Richard Arthur) served as St. Augustine’s parish priest, a position he held from 1597 until ca. 1604, when he disappears from the record. Little is known about Arthur’s past, other than that before he became a priest, he had a long career as a soldier, serving in Malta, Italy, and Flanders. After entering the priesthood, Arthur served as the chaplain of the Castillo de San Juan, in Puerto Rico. When Arthur arrived in St. Augustine in June of 1597, he was already a mature man in his early 60s.

Morning image of La Catedral

December 20 – An Unexpected Find

If there is a universal truth regarding archival work it is this: One always finds something intriguing on the last research day, something that compels you to return. Today, my final day, was no exception. As I scrolled over the final folios of this 2,000-page bundle of documents, I came across the accounts of St. Augustine’s gunpowder expenditures for the year 1600 and for the first half of 1601. The reports reveal that the powder supply was expended for a number of different reasons. While artillery pieces often were fired to help guide ships safely across St. Augustine’s protective sandbar, they were also fired during times of public celebrations and religious festivals, including the city’s Easter celebrations, and the public processions to honor the feast days of the city’s most venerated saints, including Santa Barbara (December 4) and St. Augustine (August 28), the town’s patron saint.

Among the celebrations commemorated in both years was a spring festivity to honor the feast day of San Patricio, or St. Patrick. In March of 1601, St. Augustine’s residents gathered together and processed through the city’s streets in honor of an Irish saint, who appears to have assumed a privileged place in the Spanish garrison town. Indeed, during these same years, St. Patrick was identified as the official “protector” of the city’s maize fields.

It is likely that Richard Arthur was responsible for the Irish saint’s short-lived prominence in St. Augustine. When Arthur disappears from the historical records, so too do the references to the Irish saint, and soon thereafter, the memory of the St. Patrick’s Day celebrations and processions began to fade from public memory. Today, St. Patrick’s Day is one of St. Augustine’s most popular celebrations, but its early seventeenth-century origins have long been forgotten.

As I close this bundle of documents and return its pages to their protective case, it is difficult not to contemplate the fact that the first recorded St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in the United States did not occur in Boston or New York. Rather, those who first gathered to venerate St. Patrick and process through city streets included a blend of Spaniards, Africans, Native Americans, Portuguese, a French surgeon, a German fifer, and at least two Irishmen, who marched together in honor of the Irish saint.

On March 17, 2018, the city of St. Augustine will commemorate the 418th anniversary of this “First St. Patrick’s Day” celebration. I invite you to join us as we raise a glass to Richard Arthur, David Glavid, Doña Ana, and the many other early Floridians whose stories can be found in the 42,999 bundles of documents that await the curious researcher.