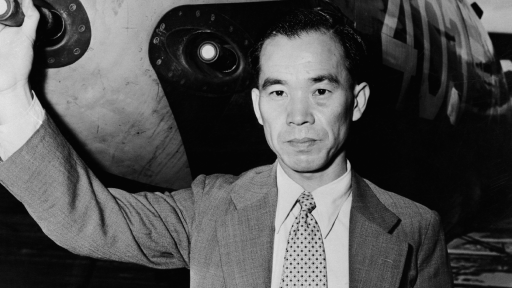

Colonel Ralph Wetterhahn, U.S. Air Force (Ret.) crash site investigator and fighter pilot.

First off, you had a long career as a fighter-pilot, then a crash investigator, then you went back to school at USC and became a writer and historian. How did all of this happen?

Colonel Ralph Wetterhahn: I was a fighter pilot for most of my 29 years in the military. I flew F-4 Phantoms, A-7 Corsairs, and the F-15 with the Air Force and Navy. During that period, from 1963 to 1992, I wound up being the chief of safety for the Pacific Air Force, with headquarters in Hawaii. They sent me to Norton Air Force Base, for the accident investigation course that they run there, which is where I learned the techniques for analyzing wreckage, those sorts of things. Also, pilots read every accident report no matter what type of aircraft is involved — it’s sort of mandatory reading for everyone. You read literally thousands of these reports, and you just pick up a lot. That’s the background that I bring to the table when we go out on these expeditions.

Guadalcanal has been researched extensively, and the dogfight between Saburo Sakai and James Southerland has already been very well documented. What do you feel that you’re able to discover in these things that have been so well investigated already?

Often what you find in a lot of historical writing done by people who may not have great expertise in the areas they’re writing about, you get some things that may not make a whole lot of sense. And that’s what I found when I read some accounts of this dogfight. As an aviator who’s done a ton of dogfights, many of the descriptions of what the Wildcat was able to do just made absolutely no sense to me. It’s a heavy, cumbersome aircraft and there are all of these descriptions of it flying better than a Zero?

And since Southerland wrote about his experience, and Saburo Sakai was interviewed about his experience, there’s the issue. What we wanted to do was try to validate, or rule out whatever claims had been made. And of course anytime you find a historic aircraft, that’s of interest in and of itself.

Col. Ralph Wetterhahn, crash site investigator, and Justin Taylan, creator of the Pacific Wreck Database, survey the island of Guadalcanal.

Did your technical background bring new light to the story?

You know, when you’re doing accident investigations, you have laboratory equipment, all kinds of gear you can use to validate things. When you do what we’re trying to do, you’re limited pretty much to the eyeball — but it’s astounding how much you can see. You have to know what you’re looking for, and you have to have some background in what happens to metal, and an understanding of ammunition and how it operates. I would never claim that my conclusions are 100%, concrete, accurate — but they’re damn close! If I see the metal pattern of impact on a propeller, I can tell you a lot about what that engine was doing, and I would stake my reputation on it.

So what does James Southerland have to say in his memoir of the dogfight about why he was unable to fire on Sakai? That’s something that you uncover in the film, but his feelings in the moment aren’t clear.

He tried to fire, and got nothing … he had clearing handles [used to clear jammed guns] in the cockpit; he activated those, and still got nothing. His thoughts were “maybe I’m out of ammo,” because he’d been doing a lot of shooting. In any case, he indicated in his writing that there was a problem with the guns, and he didn’t know what it was — so we wanted to clear that up.

And if you’re interested in understanding whether or not Sakai’s account is accurate, it seems that you need to have some idea of what Sakai was thinking. How do you go about reconstructing his frame of mind?

Col. Ralph Wetterhahn examines a .50 caliber shell from the guns of Southerland’s Wildcat recovered near the crash site.

That, I think, is one of the things we helped resolve. Sakai says at one point in the account, he pulled up alongside and looked at the wounded Southerland, decided he was no longer going to try to kill the man; he would only try to disable the aircraft. And he claimed that he fired with his 20 mm at the engine.

Well, we’d got the engine, so we could look and see if there’s any evidence of his claim that he hit the engine. And there certainly was … now you can’t say with 100% accuracy, but it lends credence to his claim. And since he chose to describe it in that manner, and the evidence clearly indicates that it happened in that manner, I have to give him credit for his comments. Now sometimes, after the fact, guys can say just about anything about what they were thinking — but this is a little different. Here you’ve pulled up alongside a guy, it becomes a little personal — I’d think you’d recall that.

Here’s something else of interest: Sakai says also that he thought he saw Southerland waving to him. And that’s certainly possible, but if you look at Southerland’s account he says that his only thought was that he had to get out of that airplane. Now in that aircraft if you undo your lap belt, you have two straps that come over your shoulder. You’re going to have to grab each one and flip it back over your shoulder, and when you do that it’s going to look like you’re waving. Now you can’t say for sure whether or not Southerland did wave, but you can certainly say that Sakai would have seen Southerland move his hands in a waving motion.

These kinds of things lend credence to these accounts, since they’re all consistent. Those little things add up to what you can conclude is the most probable account of that dogfight.

Do you feel there’s something that can be revealed by this dogfight — a personal conflict — that reveals something to you about the larger conflict?

Well I think in this conflict you can begin to see the reasons why one side prevailed over the other. The Zero was designed to be an offensive weapon — there’s no armor for the pilot, there’s no bulletproof windscreen, it’s light, fast, and highly maneuverable. The idea is I’m going to shoot you down so I don’t need any of these things, since you won’t be around to bring guns to bear against me. The American Wildcat builds a heavy airplane, but powerful, with a radial engine that can take a beating.

What happened was when our guys got hit the armor saved their lives — they were able to bail out, and talk about the experience and tell other guys about what to do and what not to do, and they were able to get back into another airplane and fly again. The Japanese pilot was unable to do that, and it cost Saburo Sakai his eye. If he’d had a bulletproof windscreen that shell that went through his skull would never have got there.

What happens is that the Japanese lose their experienced pilots … because they were unwilling to admit that they could be beaten and you might need a way out so you could fly again. You could see in the plane that the Japanese needed a quick, decisive victory — not a long, drawn-out battle of attrition. So those airplanes can tell you about the psychology of the conduct of war on both sides.

Are there a lot of people out hunting for wrecks from the Second World War? Is there a lot of interest in these old aircraft?

There’s a Betty bomber that was found in Guadalcanal recently; there was another one found a couple of years ago, with remains onboard, and some Japanese families came out to recover them. There are a lot of wrecks out there, of course in the Solomons … it goes on and on. In all of those areas, and you can go right on up into the Northern Kirils, there are wrecks everywhere. But they’re hard to get to, and it would be very expensive to bring in the gear to get them out.

What do you think drives the continuing interest in these stories of World War II?

I think almost everyone in the United States, in much of Europe, has a relative who was involved in World War II in one way or another, so they’ve heard all these stories of this period and they feel a bit of an attachment to it. Justin Taylan [who led the film crew to the wreckage of Southerland’s plane], his grandfather fought in the Pacific. I had uncles who fought in the U.S. Navy over here, and I had relatives in Germany who fought in the Wehrmacht. So I personally feel a need to look into these things … it’s just a fascinating period.