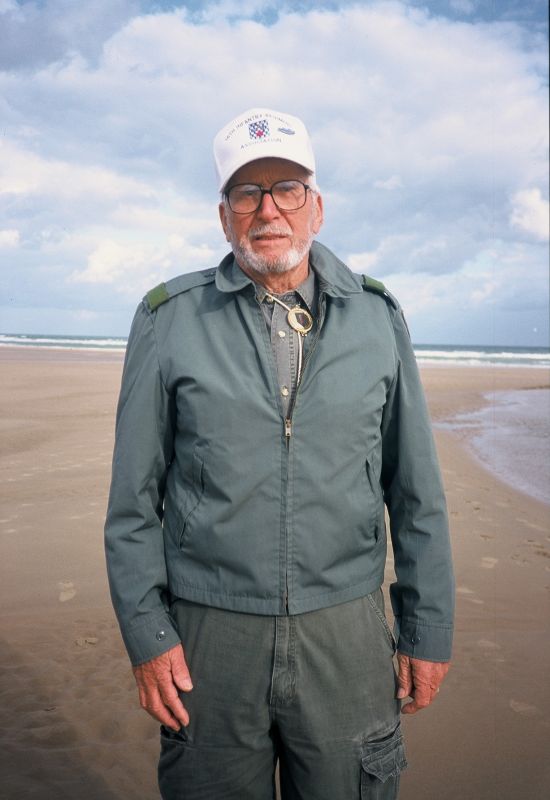

U.S. infantry member Harley Reynolds boarded a ship bound for Great Britain in August 1942. Less than a year later, he was among those who landed on Omaha Beach.

Even now, nearly 60 years to the day later, the events of June 6, 1944 are crystal-clear in Harley Reynolds’s memory. “From the boat,” he says, “I had a perspective on just about everything. I looked from my left to my right, at the entire beach, as we were coming in. I could see all the different things going on. Upon landing on Omaha Beach, my vision was a little more tunneled, because at that point I was looking for safety.”

On the beach, Reynolds found himself amid a scene of chaos and carnage. “It didn’t seem possible at that time that any of us were going to live through it, with so many bullets and so forth, and people dropping all around you, wounded and killed both. I felt that we, as the first wave going in there, were being sacrificed. It didn’t mean that the landing would have been a failure — there would have been another wave following us — but the first wave going in there would have to be sacrificed. And to feel sacrificed is a very bad feeling. You feel you are facing death, you just don’t know when it is going to come, and in what way. Am I going to be blown apart instantly? Am I going to be knocked down and bleed to death? All kinds of things cross your mind. In fear, we don’t have control over the things we think.”

Yet Reynolds kept his head. “I behaved very coolly on that beach,” he says. “I did not lose my composure and I went on to lead my section off the beach. In fact, we were the first men off the beach in the sector where we landed. Three men have been recognized for being the first men through the wire and through that beach, and two of those men are dead. I am the only one living now to talk about it.”

Reynolds has returned to Normandy twice since 1944, and he will return again in June for ceremonies to mark the 60th anniversary of the invasion. His first visit back to Omaha beach, about two and one-half years ago, “was very, very emotional,” he says. “You find you have a bond with the men who were there. We didn’t necessarily know each other, and we didn’t have to know each other. There is still a bond.” He returned for the filming of SECRETS OF THE DEAD: “D-Day,” when he was introduced to a German soldier who had defended the same stretch of beach Reynolds and his comrades assaulted. “I had some qualms about meeting him,” Reynolds admits. “I didn’t know how to accept him. I didn’t know how to act. I was afraid I might overact. But I was not cold towards him. I was friendly, I shook his hand. I had dinner with him on two occasions while I was there. He does not speak much English that we could carry on a conversation, but we had an interpreter.” (The interpreter was the grandson of the colonel who had commanded the German troops who faced Reynolds at Omaha)

After the war, Reynolds, a Virginian, returned home, entered school under the G.I. Bill, and learned a trade — tool engineering and die design and engineering. “That’s the job I followed for the rest of my life,” says Reynolds, who is now retired and living in Florida. “And for all that time, the war was behind me. I may have unconsciously put it behind me. I never read a history book about the war until 1990. I didn’t know how history had recorded the invasion, particularly [the efforts] of my section, my company, my battalion, my regiment, my division.”

That changed when Reynolds happened to meet a man who had been in his old division, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. “He told me where the outfit was now stationed — Fort Riley, Kansas — and a lot of things about it. I came home and immediately, through telephone information, contacted Fort Riley and asked to talk to someone with the 1st Division. They put me in contact with someone who told me about a reunion within a couple of weeks, in Louisville, Kentucky. I went, and that’s where I saw friends I hadn’t seen for 48 years. I had thought a lot of them were dead because I had seen them get wounded and go down.” Army historians apparently had believed the same thing: Reynolds learned that the regimental history book listed his section as killed in the early moments of the invasion. “It said my boat, the B company headquarters boat, had taken a direct hit and was sunk upon hitting the beach. From that day on, knowing what we had really accomplished, I took it upon myself to disprove those entries.”

At the reunion, Reynolds collected the names, addresses, and phone numbers of his section mates, then later bought a camcorder and went to visit each soldier to record their statements about the actual events. Based on their accounts, the regimental history books were rewritten. “It now lists me and my section as the first off the beach,” he says. “I got the history books changed.”