As they set sail from London to the distant shores of America in December 1606, the men and boys onboard the Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery surely expected the best from their adventure. They’d establish a British settlement, find gold and silver, a passage to the Orient, and, perhaps, the lost colony of Roanoke. The explorers, funded by a group of London entrepreneurs called the Virginia Company, could not have anticipated the fate that actually awaited most of them: drought, hunger, illness, and death.

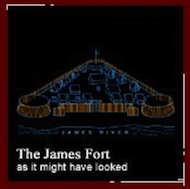

Their journey started off as badly as it ended. The three ships were stranded for weeks off the British coast, and food supplies dwindled. Over the course of the voyage, dozens died. But 104 colonists — many gentlemen of privilege, but also artisans, craftsmen, and laborers — survived to reach the shores of Virginia. On May 13, 1607, they decided to make landfall on the swampy ground of what was then a peninsula (and now an island) along the James River, some 60 miles from the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Within a month the settlers had constructed a triangle-shaped wooden fort, for protection against the Spanish, who did not want the British to establish any kind of foothold in the New World.

Their journey started off as badly as it ended. The three ships were stranded for weeks off the British coast, and food supplies dwindled. Over the course of the voyage, dozens died. But 104 colonists — many gentlemen of privilege, but also artisans, craftsmen, and laborers — survived to reach the shores of Virginia. On May 13, 1607, they decided to make landfall on the swampy ground of what was then a peninsula (and now an island) along the James River, some 60 miles from the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Within a month the settlers had constructed a triangle-shaped wooden fort, for protection against the Spanish, who did not want the British to establish any kind of foothold in the New World.

The settlers of the new colony — named Jamestown — were immediately besieged by attacks from Algonquian natives, rampant disease, and internal political strife. In their first winter, more than half of the colonists perished from famine and illness. Eventually, more colonists and new supplies were brought from Britain, and, despite a fire that wiped out the original fort, the settlement found some stability under the leadership of Captain John Smith. Smith, with the help of Pocohontas, daughter of the Algonquian chief Powhatan, managed to broker an uneasy peace with the natives before leaving the colony and returning to England in September 1609.

The following winter, disaster once again struck Jamestown. Only 60 of 500 colonists survived the period, now known as “the starving time.” Historians have never determined exactly why so many perished, although disease, famine (spurred by the worst drought in 800 years, as climate records indicate), and Indian attacks took their toll. On June 7, 1610, Jamestown’s residents abandoned the hapless town, but the next day their ships were met by a convoy led by the new governor of Virginia, Thomas West, Lord De La Ware, who ordered the settlers back to the colony.

In 1612, John Rolfe — who would later marry Pocohontas — began to grow tobacco, finally giving the colony a cash crop and hope for survival. The first representative government in the New World was convened in Jamestown in July 1619, the same year that African slaves — then indentured servants — were first brought to America. Jamestown was the capital of Virginia until 1698, when its statehouse burned down. The following year, the capital moved to Williamsburg, and Jamestown began its slow decay