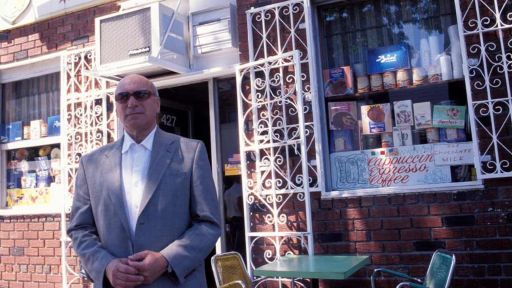

Federal prosecutors wouldn’t have had a case against Bonanno Family boss Joseph Massino for the 1981 murders of Philip “Philly Lucky” Giaccone, “Alphonse “Sonny Red” Indelicato, and Dominick “Big Trin” Trinchera, had it not been for evidence obtained by specialized investigators known as forensic accountants. FBI special agents spent two years poring through financial documents to unearth the paper trail that ultimately produced proof of the criminal activities of Massino and his colleagues.

Although it has become better known in recent years, in the wake of business scandals like Enron, forensic accounting actually has a long history. A form of forensic accounting can be traced back to an 1817 court decision involving a bankrupt estate; the technique nailed famed mob boss Al Capone on tax evasion charges in 1931.

The decomposing body of Alphonse “Sonny Red” Indelicato.

By definition, a forensic investigation of any kind is one that is conducted with the purpose of obtaining evidence that will be used in a court case. Forensic accounting is simply the analysis of financial documents such as tax returns, bank statements, canceled checks and the like, in search of proof of a criminal act, be it tax evasion or securities fraud. Because organized crime exists for the sole purpose of illegally making money, a distinctive paper trail pointing to criminal activity is produced as money comes into and leaves the organization.

In the early days of criminal investigations of the mafia, the FBI generally overlooked this trail. “The Bureau tended to be very focused on the traditional organized crime kinds of cases — murder, extortion, labor racketeering, loansharking — and was not terribly interested in doing the financial investigation,” says retired senior litigation counselor Ruth Nordenbrook, who worked in the Office of the U. S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, and prosecuted the Massino cases and others involving the Bonanno crime family. The tide began to turn in the mid-1980s, in part, Nordenbrook says, because the FBI “began to recognize the benefit of taking the bad guys’ money away — their houses, their bank accounts, their businesses. You can’t do that unless you can find the money, and show that it was the fruit of criminal activity.”

Human bones and a shoe found buried at the crime scene.

This kind of conviction will put a mobster behind bars, but not for very long; a typical tax fraud conviction will lead to no more than about three years in prison. “When you have someone who is running a violent enterprise, that is not good enough,” Nordenbrook says. What those charges can do, however, is give prosecutors leverage against the wise guys and their associates — and that’s exactly what led to Joey Massino’s downfall.

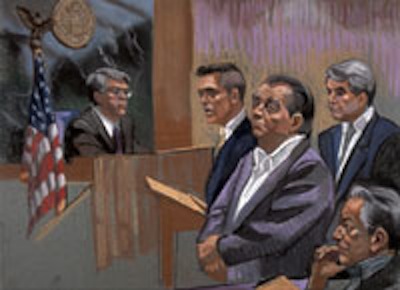

Courtroom sketch of Joseph Massino’s trial.

“When we charged Frank Coppa, it was for the extortion of Weinberg, a traditional organized crime charge,” says Nordenbrook. He soon rolled on other Bonanno members, who themselves turned, and the cascade of informants eventually led straight to Joey Massino, who was implicated in the 1981 murders by his own brother-in-law and underboss, Sal Vitale. Ultimately, Massino himself became a government witness — the first mob boss ever to do so — “and it all grew out of the tax investigation,” Nordenbrook says.