Retired U.S. Prosecutor, Ruth Nordenbrook

The mob cases, she says, had their own unique difficulties — such as witnesses not being willing to talk — “but I wouldn’t say an organized crime white collar prosecution is as difficult as a white collar prosecution of something like Enron, because ultimately it is not nearly as large and not nearly as complicated. Usually you are able to find some autonomous false statement that you’ll be able to address, or you’ll be able to prove that some guy spent more than he reported he’d earned to the Internal Revenue Service, and had engaged in massive tax fraud,” she says. “It is very common for wise guys to hide money in their wives’ names, so we would try to show that the wives had known about the fraud and they were included in any charge. That is why they hated me — I would charge the women.”

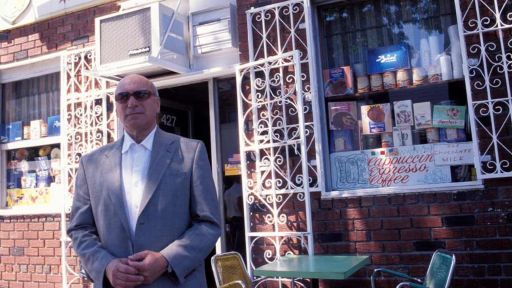

Undercover FBI photograph of Agent Joseph Pistone,”Donnie Brasco,” and Dominick Napolitano.

These days, Nordenbrook stays busy with volunteer work, but has nothing to do with law or gangsters. “I don’t miss work a bit,” she says. “I had a wonderful, interesting career and I don’t regret staying there and having done it, but recently the work had become much more pressured. In organized crime cases there is a lot more ugliness now between the defense attorneys and the government. It has become much more personal, much more acrimonious. These wise guys expect their lawyers to not be friendly with the government lawyers and to do devious things, to get them off at all costs. I never felt like I was in danger, but there have been instances where organized crime prosecutors were threatened, or had a contract out on their life — although there have also be prosecutors who were threatened by the Colombians, or other criminal groups.” Trying gangsters — of any sort — Nordenbrook says, “is a young person’s gig.”