“It was an amazing moment. I remember standing with our site manager and we looked at the first decapitated burial. … The skull had been taken off and put down by the feet, as I recall. Then we started finding other things, which were rather unusual, like a skeleton with these great, thick iron rings — shackles, if you will — around its ankles.” —Patrick Ottaway, archaeologist

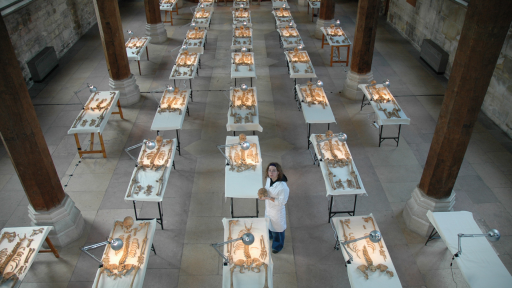

A worker at the medieval guildhall in York examines the skeletons.

In the English city of York near the ancient ruins of Hadrian’s Wall, archaeologists have unearthed more than 30 Roman-era skeletons. The skeletons are posed in a gruesome tableau of violent death, their heads hacked off and placed between their knees, at their feet or in other odd places, suggesting desecration and humiliation, even in death. One is found with heavy iron rings around its ankles, an aberration in the Roman world. Who were they? Pagan prisoners savagely murdered? Soldiers killed in battle or executed for crimes against Rome?

To solve the mystery, a team of investigators posits compelling theories and puts each one to the test. Headless Romans follows the progress of the team’s researchers as they examine the evidence within the context of a key, transitional period of Roman history marked by fierce sibling rivalry over the imperial throne.

“Modern forensics, ancient relics, historical records, and re-enactments all come together and make for high drama in this documentary about one of the more baffling archaeological discoveries in recent memory,” said Jared Lipworth, executive producer of SECRETS OF THE DEAD. “It’s fascinating to watch as science and scholarship converge and a vague chapter of ancient Roman history is essentially re-written.”

SECRETS OF THE DEAD: Headless Romans opens with a high-angle shot of the grand interior of York’s medieval guildhall, where rows of decapitated skeletons from the excavated site are laid out on steel tables for examination. The program juxtaposes this startling image with scenes of magnificent Roman ruins, connecting the skeletons to the greatest civilization ever to rule the ancient world, with an empire that stretched from North Africa to present-day England and beyond. At this point, the investigators know the general period of the skeletons, but not much else.

Scientists discovered that vertebrae fragments on the skulls were marked by the blade of an axe, sword or similar weapon.

First, human bone specialists Katie Tucker and Charlotte Roberts are called in. They quickly determine that all of the skeletons are male. A state-of-the-art microscope reveals stunning, three-dimensional images of vertebrae fragments marked by the blade of an axe, sword or similar weapon. But was this the cause of death? Or were the heads removed posthumously as part of some mysterious Roman burial rite? Archaeologist Robert Phillpot and historian and author Miranda Green discuss Roman superstitions and beliefs about death and the afterlife, offering a possible context for the latter theory. But the skeletons show signs of extreme violence. One was found buried face down with a large hole in its skull. This evidence seems at odds with the deliberate, surgical cuts that would have likely been used in a ritual decapitation or burial rite.

Pottery from the site dates to the early third century, when Septimius Severus used violence to bring stability to an empire previously fragmented and weakened by civil war. Severus and his army led brutal campaigns against the Caledonian tribes of Scotland beyond Hadrian’s Wall, which had been built by the Romans to mark the limits of their empire and keep out those they deemed “barbarians.” By A.D. 208, Severus’s efforts assured that the prosperous, pluralistic city of Eboracum, at present-day York, became a military stronghold and a key center of the Roman world.

The enamel of a tooth, which scientist Janet Montgomery describes as “a little archive, a little snapshot…that people carry around with them wherever they go,” helps determine the origins of the skeletons. She uses the advanced technology of an electron spectrum device to cull data from many different samples and discovers that these men came from Germany, the Alps, the Mediterranean, and Africa. Her findings help dismiss one theory that the skeletons are those of local Scottish soldiers or prisoners. It is a major breakthrough for the investigative team.

But what about the skeleton with the iron shackles around its ankles? Archaeologist Patrick Ottaway doesn’t believe that the shackles, which were soldered onto the legs without chains, were designed for a prisoner. “It conjures up an awful picture,” he says, speculating that the shackles were meant to contribute to a terrible and humiliating death. “You would have an open wound as a result of putting the things on in the first place, and then the things chafe and cause further inflammation, so by the time the poor fellow finally passed on he would have been in considerable pain.”

Photo of skeletal remains. Archaeologists have unearthed more than 30 Roman-era skeletons In the English city of York, near the ancient ruins of Hadrian’s Wall.

Back at the dig in York, more human remains are being unearthed. Even the particular spot where the skeletons were found is a piece of the puzzle. These men were buried in the cemetery’s “Mount,” an exclusive section reserved for wealthy, prominent citizens, not common soldiers.

Headless Romans introduces the Emperor’s inner circle, the key players in the story behind the decapitated skeletons, including his sons, Caracalla and Geta; the family tutor, Euwodus; and Castor, the Emperor’s chamberlain and most trusted official. The bitter rivalry between Caracalla and Geta is vividly recounted. After an ailing Severus made the brothers joint emperors, Caracalla embarked on a bloodthirsty campaign to seize the throne exclusively for himself. He killed scores of people, and even made attempts on his own father’s life. Ultimately, he would kill his brother and rise to the throne as sole Emperor.

In the end, it is historian Anthony Birley who combines the forensic and archaeological evidence with the writings of another historian — the ancient Roman Cassius Dio — to solve the puzzle. The skeletons discovered just a few years ago in York were the victims of Caracalla’s blood-thirsty purge in the early third century, the result of a public execution carried out in the spring of A.D. 211. Birley’s research even enables two of the victims to be named: Castor, who had been Severus’ loyal chamberlain, and Euwodus, the tutor.

Caracalla stopped at nothing in his jealous quest to rule the Roman Empire, but ultimately, his reign would be short. After only five years as emperor, he was killed by one of his commanders. But now, thanks to modern forensics, Caracalla’s victims are speaking out, telling their secrets and sealing his callous legacy.