TRANSCRIPT

Jamestown: the first permanent English colony in the New World. One chapter in the beginning of a new country. But the colony has a dark secret. A horror, hidden away by time.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: Rumors had already started to reach London of the horrific things that were going on in Jamestown.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: Things got very, very bad, very quickly.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: It must have been an absolutely terrifying event.

June 1609: A young girl leaves England, bound for Virginia, full of hope.

April 2012: Archaeologists in Jamestown find a definitive clue… the long-lost key to a disturbing mystery.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: The blade comes in.

Karin Bruwelheide, Smithsonian Institution: After these chops, you move to the back of the head.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: It must have been horrible.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: We’re looking at this and we’re thinking “wow.”

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: This probably has something to do with the cause of death. Could this be a murder?

The encounter between modern science and the remnants of the past will change the way we see the birth of America.

In the summer of 1609, a fleet of English ships sails across the Atlantic – bound for the American colony in Jamestown, Virginia. A young girl is among the hundreds of passengers. A girl whose real name may never be known.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: The young girl is aboard and this is part of the biggest fleet to have left England for Virginia. It carried over 500 settlers, 9 ships. Jamestown had been founded two years earlier but had not prospered and in fact the first couple of years of Jamestown’s history is pretty much a colossal failure.

Jamestown is doomed from the start: The colonists settle on a marshy island with no fresh water, where crops fail and malaria flourishes.

Of the first 104 settlers who come to Jamestown – all men – only 38 survive even the first seven months. The next year, fire nearly destroys the entire settlement.

The English had tried to settle America before with little luck; a colony was seen as a place where a person went to die.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: This was really a tough place. To establish this colony it was difficult, and dangerous.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: Most colonies fail, most colonies were lost colonies. And they usually failed within the first twelve months for a variety of reasons: extreme weather, lack of supplies, Indian attacks.

Two years after its founding, the desperate colony of Jamestown still cannot feed itself. Already this is the third expedition sent to Virginia – a third emergency rescue mission. Perhaps this time, Jamestown will be saved.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: So the young girl is part of this great effort to reestablish the colony and there was a grand vision for an English New World, an English America that would in time rival the great Spanish Empire to the south. This fleet carried the hopes of the nation, and she went with those hopes too.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: She was a young woman, very young, and would have probably left her family behind.

She's left England behind as well. This is the England where Shakespeare has just published his sonnets, and his plays run at the Blackfriars Theatre…

…but it’s also the England where thousands die from rampant smallpox and even the bubonic plague. The Virginia Company of London offers a chance to start a new life in America, knowing full well how dangerous the enterprise really is. Some on board have left England in the hopes of getting rich; some hope for adventure; and some have no choice.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: You would need to have-you know you would need to sort of collect these people, sometimes from prisons.

The girl is likely a servant for a wealthy family.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: They’re crammed aboard these ships with livestock. Women and children would have been kept below decks. For a young woman who’s a maid servant in a family, this is probably the biggest trip that she has ever taken in her life, and the trip must have been absolutely horrible.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: On board a ship, you’re dealing with sailors who come from rough backgrounds, you’re dealing with a situation that’s uncomfortable, dangerous even, the sights, the smells, the sounds - there’s going to be a lot of fear and fright. These are the people you might have been warned about your whole life.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: On one ship two women gave birth, the children died. But one of the ships that came over is recorded as having the plague on it, so we know that there was quite a lot of death - at least 30 individuals were tossed overboard on route, that’s recorded. So it was a—it was a horrific voyage.

Real disaster strikes on July 25th, 1609. A brutal storm off the coast of the Azores… it’s “like a hell of darkness turned black,” one man writes.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: Violent storms break apart the fleet, the ships are scattered, battered, broken, masts are being torn off, one ship turns back and is presumed lost.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: It was a terrifying experience. Six ships, including the ship with the young girl onboard, carried on to Jamestown, many of them in pretty bad condition. Many many of the settlers sick, many of the mariners injured, many of the supplies had been ruined.

But finally, the ships limp up the James River and arrive... at Jamestown.

Dr. William Kelso is the longtime Director of Archaeological Research at Jamestown.

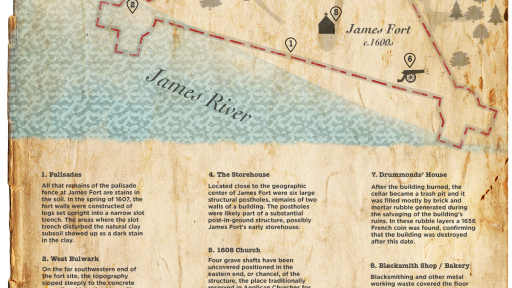

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: We’re here at the site of original Jamestown. It was first settled in 1607, and it lived on to be the first permanent English settlement in the New World. We've been excavating here for over 20 years. What we’ve discovered since we began was the outline or footprint of a triangular fort almost 500 feet of wall line or palisade line around it. And we’ve also been uncovering various buildings that were built through time within that fort.

Kelso's team has already made many remarkable discoveries…

Decoding the cryptic messages in the bones of Jamestown’s settlers.

They've found Bartholomew Gosnold -- one of the colony's leaders, captain of the ship Godspeed -- buried in a gabled coffin near the parade ground.

Even the colony's first fatality -- a teenaged boy killed in an Indian attack, an arrowhead still embedded in his leg. …Though the scientists tell us an infection, spreading from an abscessed tooth, would have killed the boy soon enough.

Incredible discoveries. But none of them compare to what they're about to find.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: Now we’re inside the fort. Inside the three walls of James Fort of 1607. We know that from archaeology that began in 1994. Inside the Fort we found a number of building sites and one of the most significant buildings that we have found is a cellar right over there.

This cellar, in the end, will reveal some of the saddest secrets in the history of America.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: This is a building site that we call 191. The reason we know it’s a building is because it has architectural features to it. On one side we uncovered a set of steps down into an L-shaped cellar. And in it are bake ovens, so we felt like this was a kitchen of 1608.

Mary Anna Richardson, Historic Jamestowne: One of the earliest features that we figured out was just above here we had a circular, kind of oval area of burnt clay up top... Then as we work through those trash layers pulling those out of the cellar they reveal brickwork as a front façade for the opening entrance getting into this oven here.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: This becomes the earliest brickwork in English America.

Jamie May has worked with Bill Kelso since the excavation of James Fort began, 18 years ago. She's now a senior archaeologist at Jamestown.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: So we’re digging in a trash layer and we’re finding the objects you might normally find in a trash layer including trade items, including ceramics.

The age of the artifacts pinpoints the era when the cellar was used – the early 1600s.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: Every last bit of soil that we excavated from that cellar kitchen has to go through a screen, and that screen catches the smallest artifacts that you can imagine.

More than 47,000 artifacts have been found here.

Danny Schmidt, Historic Jamestowne: In that window mesh we’re catching very small Venetian glass trade beads, little beads made in Venice – as well as a lot of animal bones.

Man 1: Wow look at that. Look at the blue.

Man 2: I never knew they put blue on, uh, Bartmans.

Man 1: That’s really a nice blue too, isn’t it?

Man 2: Wow. That is amazing.

Man 1: Look at the blue on the-

Woman: Oh wow.

Structure 191 is a treasure trove of European history…and it's about to change American history as well.

Mary Anna Richardson, Historic Jamestowne: That dirt…is…yes… mmm.. That part’s real fragile too. Well now it’s loose. ...

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: We found that we were getting a little bit of a strange assemblage that included things like cats and dogs and horses.

Finding skeletons of domestic animals provokes questions immediately.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: Which was a little bit more unusual -- you wouldn’t expect for people to be throwing these animals in the trash so, what’s going on here?

The discarded animal remains would be just the first strange discovery in Structure 191....

To the colonists, the ships arriving in August 1609 seem to be a godsend.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: Six battered and broken ships reach Jamestown.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: On one of those ships was the young girl.

The nameless girl has made it to the New World at last. She's kept her appointment with destiny.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: But this was not the great fleet that the colonists already in Jamestown expected to see. Many of the supplies had been ruined, and there was inadequate food for those who were arriving, maybe about 300 settlers, and those who were already in the colony.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: They kind of limped in here to Jamestown with the hopes of salvation here and instead they came during the worst possible time period.

The girl has come to a world that is new, vast, and strange. Of the 130 people already at Jamestown, only two are women.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: Women in our early Jamestown period rarely get mentioned unless they do something naughty, and for instance we know one of the first two women who arrived, Anne Burris was a maid servant, she got in trouble for cheating on sewing a shirt for servants in the colony and got caught at that and was whipped publicly and unfortunately she was pregnant and lost her child.

What challenges await the girl? What adventures?

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: She had arrived with great hopes, great hopes that this would be a new life and a new world.

The new settlers may be arriving with their hopes intact... But they bring no food at all. None.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: People in Virginia, they’re hoping to be resupplied and probably the last thing they want to see is 6 ships land without any supplies. More hungry mouths to feed and an already dwindling food supply, and this girl was one of them. It was a blazing hot summer during a period of drought, and unlike the Pilgrims, this colony was never able to sustain its own crops and become self-reliant.

What kind of life will the arriving settlers find in the New World?

George Percy, one of the original colonists, and the President of the settlement, described it this way:

Voice of George Percy, President, Jamestown Colony (1609): There were never Englishmen left in a foreign Country in such misery as we were in the new discovered Virginia.

400 years later, in the cellar of structure 191, researchers begin to find clues to a timeless riddle.

Mary Anna Richardson, Historic Jamestowne: It was a typical Monday morning; you come into work and you never know what you’re going to find.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: Well we’d been digging in this L-shaped cellar for three or four months when we started finding something that was not an animal remain. One of the students on her swipe across the layer of soil hit teeth. And she alerted me to it and so I went over and took a look and yeah they looked like human teeth to me. We found teeth and a jawbone and other fragments that were not cats or dogs or horses, but we could say conclusively that these were the bones of a human being.

Jamie May knows that finding human remains in a trash pit is a very different matter from finding them in a proper burial site.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: When Jamie came to me one day as we were digging the cellar and said, “I think you better come down and take a look at something here, I think we’re finding human remains.”

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: We were over in this portion over here. Right almost exactly right here in the trash layer where we’ve been working.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: I thought I better take a look at this pretty close so I went down and take a look and sure enough…

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: We were really awestruck once we realized what we had found. We’ve uncovered actually some human remains. This is a cranium, in situ, and right next to it there’s a native pot and we’re gonna try and remove these intact right now.

It's a delicate and time-consuming task.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: Right now we’ve taken out the native pot that was right here so we’re gonna try and pedestal this around so that we can remove this as one big block of dirt and then excavate it in the lab.

Mary Anna Richardson, Historic Jamestowne: So finding these remains in the context in which they were found was super exciting. We all knew that this was going to be big, almost as big as when we found the fortification.

Their hope is to extricate the bones in one single block of dirt, leaving the full excavation for a more controlled environment.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: The major questions that occurred to me when I first saw the remains, why is it here? Why is it in with, in the trash? The next question, well how did this person die? Who was this person?

The bones are immediately brought to the onsite laboratory.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: Tight temperature and humidity controls are necessary in order to not cause any further damage to the human bones that haven’t seen the air in 400 years. We usually do the real fine excavation of the remains in the lab here at Jamestown using small picks and brushes, being careful not to put any marks on the bones.

Within hours, the scientists come to their first major conclusion: They believe they can tell the gender of the person to whom these bones belonged.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: Look at how thin and slight this is.

Man: Young girl.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: Yeah. Around those two missing teeth which might speak to her health at the time. You can see the roots and everything and how thin walled that is. That doesn’t look healthy.

Woman: No.

Man: Poor girl.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: It had all the characteristics of being a female, which was a pretty exciting because there weren’t that many women.

The bones belonged a young woman or girl. Determining her identity will haunt the scientists. Who was she?

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: Quite early on we actually talked about naming this young woman. We thought this would give her her dignity and enable her to tell her story in a way that would not turn people off if if we could personalize her. Finally we came upon Jane -- like Jane Doe.

Jane. These are the remains of the unnamed girl who arrived in Jamestown 400 years ago. The archaeologists are beginning to untangle the mysteries of Jane’s life.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: That summer, the colonists managed to plant a 7-acre stand of corn. So at least they had that meager supply to live off of.

But trouble awaits the colony. The entire crop of corn is devoured just three days after Jane arrives. There will be not another harvest.

One man might be able to save Jamestown: the legendary John Smith, president of the colony. Smith is a deeply practical man – he trains the settlers to farm, repairs the fort, and trades with the natives.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: He organized work crews, he had the first well dug.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: He was someone with the common sense to get the settlers through these difficult times. One story about John Smith that everybody knows is the story when Pocahontas supposedly saved him from being executed by her father.

The Pocahontas story is at least partially true. But not everyone in Jamestown loves John Smith.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: He’s probably exceeding his authority, but he’s simply kind of going commando here and saying, “You know what, this is what we’re going to do and I’m going to make you do it.”

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: Some of the gentry leaders accused him of being vainglorious, unworthy, ambitious -- he did not take kindly to being told what to do by his social superiors. And of course that led to a lot of conflict. In October of 1609, there is a so-called accident where an explosion takes place with his gunpowder in a pouch and he’s severely injured. But I think it was no accident. I think it was an assassination attempt.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: So John Smith left. At his earliest opportunity, he took a ship back to England to recuperate.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: And he was never allowed to return to Virginia.

Just two months after Jane's arrival, Smith is gone forever. Relations with the Powhatan Indians deteriorate quickly.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: The English really depended on the Powhatans for food supplies. But the Powhatan had decided that enough was enough. With the spread of English settlement, they no longer wanted to support the English. They wanted to get rid of them. And so in the fall of 1609, they attacked, and they laid siege to Jamestown.

The settlers are trapped. The Powhatans kill anyone who ventures outside the fort.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: For those inside the fort, death awaits them outside the walls. This same fort that was supposed to protect them from the Spanish and from the Powhatan has now become a coffin. And the people inside are feeling hunger, they’re feeling the stress, they’re starting to break down. There’s sickness and starvation. By November they’re completely out of food.

Voice of George Percy, President, Jamestown Colony (1609): All of us at Jamestown began to feel the sharp prick of hunger, which no man truly described, but he who had tasted the bitterness thereof, a world of miseries ensued.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: And there’s also disease. And we know today what’s causing that disease. The wells are polluted with E. coli. There’s things in this water that’re going to kill people.

The water contains not only deadly bacteria, but also traces of arsenic. It’s poisonous.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: Bad water conditions, disease swept through the colonists.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: 300 individuals, confined to the fort. Many of them sick, we know that some had the plague when they arrived.

Jane: How’s he doing?

Woman: He has fever.

Jane finds herself in a living nightmare.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: With winter coming on, and with supplies in a desperate state, this was the fate of the young girl and other settlers as they looked to the future with no hope of resupply from England anytime soon. Disease swept through the settlers during these months in the fall of 1609, probably dysentery and typhoid and intestinal diseases.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: We know about this because George Percy, their commander, was trapped inside the fort with everyone else. And he talked about the cholera, he talked about the diseases, and what he referred to as the Starving Time.

According to the historical records, the settlers are beginning to eat anything.

Voice of George Percy, President, Jamestown Colony (1609): Having fed upon our horses and other beasts as long as they lasted, we were glad to make the shift with vermin, as well as dogs, cats, rats and mice.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: They have no prospects of food. There’s nothing to eat so, the monster of hunger is loose.

For Jane, hunger changes everything... What was once revolting is now a secret prize -- to be guarded carefully.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: Things got very, very bad very quickly.

Jane is a witness as death and disease grip the colony.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: She’s a living breathing person in a time period where people are dropping all around her.

It seems she's come to the New World just to watch people die.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: Over 3 out of every 4 of the settlers die during the Starving Time. Most of them are dead by Christmas.

Over the next 6 months, some 240 of the roughly 300 settlers perish.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: It would be hard to hang onto hope seeing all this happening around you, people dying, and then witnessing what people have to do to survive.

Most of the people in Jamestown... do not survive.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: You’re talking about a siege, you’re talking about fractured leadership, you’re talking about a lack of purpose, you’re talking about all the conditions where civilization, where the veneer thereof breaks down. When you’re talking about Jane, you’re talking about a teenage girl who’s in the midst of all this chaos. People are going insane.

The End of Days has come to Jamestown.

Mark Summers, Historic Jamestowne: In these conditions, in this sort of Lord of the Flies scenario, anything is possible. Even a murder at Jamestown wouldn’t be surprising considering the stress everyone is under.

What will become of Jane? In the Jamestown lab, this question is about to be answered.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: We didn’t see those before. I don’t know if those are natural or not but that sure does look like cut marks or something… Upon excavation the human remains showed some telltale marks that indicated trauma.

Violent trauma…

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: We’ve been working at Jamestown for 20 years and we have found over 2 million artifacts, we found over 80 burials, and none of the burials showed any signs of as much trauma as we could see just on this skull.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: You can maybe see them better…you can see that we have more cut marks here…one…two…

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: My first idea was murder, could this be the cause of death? 400 years later it’s hard to know in what sequence things happened. Jane died and then was hit very hard on her head, or she was hit very hard on her head and then died. The one is murder, and the other one is something else.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: It wasn’t easy to read Jane’s bones. They were telling us very different things. On the one hand there was serious trauma, and if this happened at the time of death, we could be looking at a homicide. But on the other hand, her bones were telling us that she was not in good health either and she may actually have been starving.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: I bet you there’s even more fine ones like we saw in the…two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen…there may be twenty plus. Really fine ones, right there.

But the jawbone, with its unusual cut marks, is not the only strange clue. In the summer of 2012, the excavation in the cellar slowly and laboriously reveals another bone. It's a tibia -- a shinbone. It too is human. A bone, in fact, from a small person.

Dan Gamble, Historic Jamestowne: Then when we brought in the tibia it all started to come together, in my mind anyways.

The scientists suspect this bone is somehow connected to the jawbone they found. The most crucial find in Structure 191 is a cranium -- which probably also belongs to the same set of remains.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: Once the cranium was excavated, there’s some marks on there that are real unusual. And we were able to see some of that during the excavation. You could see that there were some marks, but until the soil was removed, it wasn’t really clear that these were such big hack marks basically.

The four cut marks on one side are clear... without any doubts. And on the back, something has chopped right through the skull.

Man: Why would you have marks on the front and the back?

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: Jane’s skull obviously showed cut marks on the forehead and a heavier blow to the back of the skull. I really wanted to look at it more closely to see if perhaps this was the sign of a violent death or murder.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: We saw more and more marks that were pointing to a possibility even more bizarre than murder. Frankly, I was speechless. We look at this and we’re thinking, “Wow, this could be evidence of cannibalism.”

But this is not the first time that word -- cannibalism -- has been heard here. For four centuries, dark rumors have surrounded Jamestown.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: I’ve been reading the historical records that relate to the early events at Jamestown for 20 years. I had personally never believed them. I thought they were exaggerations, and many historians dismissed these documents as well.

But George Percy's words have now taken on a new meaning.

Voice of George Percy, President, Jamestown Colony (1609): Now, with famine beginning to look ghastly and pale in every face, nothing was spared to maintain life, and to do those things which seem incredible, such as to dig up dead corpses out of graves and to eat them.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: And that’s what we think happens to Jane.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: It must have been horrible. And I’m sure that she welcomed death when it came.

But the scientists want to know more about Jane. What happened to her after she died? To find out, Bill Kelso asks for help from the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington D.C.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: We let the bones tell the story.

Douglas Owsley is one of the leading forensic anthropologists in the nation.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: I work with law enforcement agencies in the identification of human skeletal remains. I have worked on the Branch Davidian Compound, Waco; I assisted the identification of men and women that were killed in the Pentagon plane crash. One of my early cases was Jeffrey Dahmer's first victim. Over the years I’ve looked at approximately a hundred different skeletons, complete and partial skeletons, that have been found on Jamestown Island. I’ve never seen in any of those others anything like what we saw in the Jane case. Jane is totally unique.

Just the photographs sent from Jamestown give Doug some vital clues about Jane.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: You can look at the teeth and when you look at the teeth you see that there’s a first molar, most people get them at age 6, second molar, most people get them at age 12, and the third molars aren’t showing up here, we don’t see the third molars, so they’re still actually still up in the sockets. That’s our best indicator as to as to the fact that we’re dealing with someone that’s about 14 years of age, a clue that we’re really dealing with an adolescent, dealing with a teenager.

Jane's bones themselves arrive in Washington, D.C.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: Dr. Kelso’s team brought the package up. Everything’s very carefully packaged. We have about two-thirds to three fourths of the cranium and the lower jaw, and we have part of her leg bones. The first thing that just strikes you when you see Jane’s remains are all of the numerous cuts that are found on the bones, cuts and chops.

What caused these marks? What happened to Jane? The story begins to materialize. It's a story that's all written in the bones -- especially in the cranium, the most revealing of the remains. Karin Bruwelheide, Doug's long-time associate, will help explain.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: Well the first thing that really grabbed me is when I saw the frontal. You had these four striations. They’re very closely spaced, they’re all the same size.

Karin Bruwelheide, Smithsonian Institution: They are really telling because they are very parallel...and because of that you knew then that the individual wasn’t moving when they were made. You know, it’s just like analyzing a forensic case: if this individual was alive, it would have been struggling to get away presumably, and so the fact that they’re all very nicely aligned on that frontal bone indicated to us that she was already dead when these cuts were made.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: It’s not a case of murder. All of the chops that we see, all of the damage that we see, occurred after the death of this young lady. But then you shift your attention to the back and that’s where really the force is.

Karin Bruwelheide, Smithsonian Institution: As far as the opening of the skull here, I have a little bit more sentimental notion that they would not have wanted to see the face of the individual. If you’re looking at the person that you’re trying to butcher, I think it would be more amenable to turn the face away from you and to actually concentrate then on your objective.

If the story the bones tell is true, the person butchering Jane could not bear to look at her face.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: And the strikes are coming down now, and you can see that there are four clear chops to the back of the head. And it gouges into the bone about a distance of two millimeters. And it strikes once, strikes twice, then another impact and this impact here is even deeper.

The gruesome work is not easy.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: And then there’s another really significant cut that I think is the one that in this whole process actually completed the fracture. It basically splits through and cracks the cranium at this point. The skull was being split open.

Karin Bruwelheide, Smithsonian Institution: The person who was doing this would have been attempting to remove the brain.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: The brain is rich in nutrients, it’s got lots of fat in it, it’s not uncommon in terms of 17th-century diet to include animal brains in food dishes.

The terrible truth is the survivors were forced to resort to cannibalism.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: What we have with Jane is what we call survival cannibalism.

Jane was eaten so that the others could live. At least three people were eaten in Jamestown during the dark winter. Further testing will reveal more about Jane -- and the people who ate her. Doug wants to examine her bones more closely.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: We start thinking of how to best document the cuts and chops. We decided to work with Scott Whittaker in documenting the photographs through stereo-zoom microscopy, magnification if you will, and we decided to use scanning electron microscopy.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: What magnification are we here? How many times are we seeing that?

Scott Whittaker, Smithsonian Institution: So we’re at about 16... 16 times.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: So 16 times the original cut. It’s a strange type of cutting. Instead of just going in and forcefully slicing, it’s a sawing type of motion where they’re going back and forth, back and forth numerous times. When you look at this under the scanning electron microscope you can just see how the blade goes up and down and all around -- it’s just a, it’s a very kind of inexperienced, unusual type of dissection. What’s so unusual to me is this motion here where it’s clearly an up and down, raking against up and down the mandible and then losing the track, going this way, this way, all over - anybody with the skill in butchery, in kitchen work, wouldn’t do that at all. What they’re trying to do is remove those tissues that have not only the external skin and dermis and underlying tissue, but also muscle underneath that. It’s patterning after what you would do in animal butchering, it’s just being done very awkwardly. Bottom line is that the person really didn’t know how to use a knife.

Scott Whittaker, Smithsonian Institution: So we also have to remember that this is a little girl, so we have to consider that as we look at these tool marks, you know, they’re tentative, they’re not confident. I mean this is a person, this is somebody they know.

Jane’s bones tell us both how she was butchered and how difficult it was for the people who performed the task.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: Were these people really monsters? No, I think they were just normal people that had to survive. They were ordinary people who were starving, people like us.

Modern technology can tell us even more about Jane. The Smithsonian team uses a single tooth to test the chemical isotopes in her body.

William Kelso, Historic Jamestowne: We know that from the forensic analysis that she was a 14-year-old English girl, probably from the South Coast, based on stable isotope tests of the teeth. We can know that she’s English because the stable isotopes tells us that she was raised on wheat and barley, the European food stuff, instead of corn, which is American.

The isotope tests reveal that Jane only lived in Jamestown for a few months, in 1609. She arrived in August and she died that same year. And then, her flesh was eaten.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: Many of these were considered tall tales. But now, we know that they’re true. That we have physical evidence that shows us that cannibalism did take place here at Jamestown in this Starving Time period. Driven by insufferable hunger, colonists were forced to do those things that nature most abhors. Eat human flesh.

Jane’s bones serve as decisive physical evidence of cannibalism.

Jamie May, Historic Jamestowne: With Jane, after 400 years, we now have the body, and the marks on her cranium are the smoking gun.

The scientists already know quite a lot about Jane. But one mystery remains: what did she really look like? Dr. Stephen Rouse, forensic researcher at the Smithsonian, may help answer that final question.

Stephen Rouse, Smithsonian Institution: Dr. Owsley brought me in on this case because of the experience that I had in doing the 3D modeling and reconstruction on living people.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: We’re storytellers. We tell stories based on people’s lives, based on facts. We wanted to do a reconstruction of this individual, we wanted to see what she looked like and be able to convey what we’re seeing in the bones to the public. To do that, we needed the complete skull. We needed to be able to rebuild back with the entire skull in order to do a complete facial reconstruction. We needed to be able to see not just the right side which was more complete, we needed to have the left side complete as well. That’s all essential steps in doing a facial reconstruction.

Stephen Rouse, Smithsonian Institution: If we were to mirror this right now, and by mirror what I’m talking about is I’m just taking this piece and creating a mirror image of it, a mirrored digital image. Because we want this to look like a real person. We want it to look like Jane.

Douglas Owsley, Smithsonian Institution: In order to finish this story we needed to meet Jane. We needed to see what she looked like. We had finalized the skull and that served as a template for a forensic sculpture.

They contact Ivan Schwartz, who creates casts of historical figures. Building Jane’s face requires skills in both science and art.

Ivan Schwartz, StudioEIS: We received this digitally reconstructed skull of the girl who died more than 400 years ago, whose skull was in many many pieces.

Using the model, the artist gets to work. He begins to sculpt a human face out of clay.

Ivan Schwartz, StudioEIS: We had two copies of this: one as a reference, and one to actually work on. With all the tissue depth markers in clay…

The markers indicate how deep to layer the clay, as the artist brings the skull to life. Tissue and muscles -- a face begins to take shape. Finally, we can look into her eyes. Four centuries later, it's Jane.

Ivan Schwartz, StudioEIS: I think that this reconstruction will give people a sense of what people did look like 400 years ago.

The reconstructed Jane also opens a window into the lives of the people who lived and died in the Jamestown of 1609. And now Jane lives on as the focal point of a public exhibition at the Jamestown Museum. The reconstruction is the result of collaboration between scientists -- patient work with endless attention to detail. And today, visitors can look at Jane and understand her story.

Michael Lavin, Historic Jamestowne: Archaeology has given Jane a voice that she did not have.

The surviving settlers of Jamestown discarded her remains. They didn’t even have the strength to give her a proper burial. But that’s what made it possible to tell her story today.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: Jane is one of a kind, and the chances of finding the remains of a victim of cannibalism are so remote as to be unimaginable. This is an astounding discovery.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: From the tests we’ve been able to do on her bones, we now know more about her than we do of any other woman during that early time period. But now she is sort of representing all those young women who very bravely came to Virginia in those early years.

Jane could not have known what awaited her in Jamestown -- just as we never knew her, until now.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: Jane certainly puts a face on the Starving Time, especially a female face and we know so little about the women who were here in those early years. At first we just had a few bits of bone, a skull, but now we’ve been able to study it, we put her together, we’ve done a facial reconstruction, she’s able to tell her story, and… Wow, what a story.

Jane was a girl from the coastal plains of England, just 14 years old. She arrived one hot summer, one face in a crowd of many. The New World, and her new life, stretched out before her.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: To have physical evidence that cannibalism had taken place here was an incredible find. No other site, archaeological site, in any part of the Americas throughout this entire colonial period, 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, has ever come across an example of cannibalism from physical remains.

Bly Straube, Historic Jamestowne: Jane tells us a brutal story, but it is heroic too, because we can read in her bones the kinds of things that people had to go through to establish our country.

We now know much about her physical life and death. But, still, nothing about what she thought or felt in those few hard months in 1609. Did she fear for her life? She lived through the worst of times: Hunger, disease, violence, death. Her remains show us how hard it was to forge a new nation in the swampy, malarial land surrounding James Fort.

James Horn, Historic Jamestowne: Jane, her story, is not the kind of view that most Americans have of our founding. Where they might be thinking of maybe one tough winter, but feasting with Indians and getting through, and thereafter peoples living in harmony, the actual story is one that is much much tougher and one that carries tragedy. But it’s also a story of great fortitude, of great endurance, and that I think, is the true story of Jamestown and the beginnings of early America.

400 years later, Jane speaks to us. She shares her story of what life was like in early America.