TRANSCRIPT

Leonardo da Vinci is one of the world’s greatest artists.

His masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, is known to everyone: over 6 million people view it every year.

The Last Supper is a landmark of art history.

But Leonardo was more than a painter – he was also a musician, writer, and showman.

And it’s in the pages of his notebooks we find the true Leonardo: the man of science.

His quest for knowledge led him to investigate an astounding range of subjects.

Fritjof Capra – Historian of science Leonardo’s science cannot be understood without his art. And his art cannot be understood without his science.

Leonardo drew everything he saw, and everything he imagined.

He pushed science forward in the fields of anatomy, engineering, optics, geology. Most of these disciplines didn’t even have names at the time.

His notebooks contain plans for hundreds of technologies common today: machine guns, diving suits, construction cranes, robots, flying machines.

His inventions have given him the status of a towering genius, a prophet who anticipated the modern age by 500 years.

But was he?

As researchers probe Italy’s 15th century technical revolution they are discovering precedents for many of Leonardo’s most remarkable innovations:

Some are from Leonardo’s contemporaries, others predate him by a 1,000 years.

Could it be that Leonardo is not the legendary isolated genius we take him for, but has in fact presented the work of others as his own.

Is Leonardo da Vinci a copycat?!

TITLE SEQUENCE

At his death in 1519 Leonardo was a famous artist, but his scientific achievements were less well-known.

His notebooks, written in a secretive reverse script, went unpublished for more than 400 years.

They provide insights about Leonardo the man, and about the dynamic period in which he lived. But they also raise questions.

Some of his sketches are very similar to those of other inventors. Did Leonardo steal their ideas?

There is the parachute – one of many inventions attributed to Leonardo.

Leonardo

Bartolomeo, no, no, no! You must do it

Bartolomeo

But Maestro Leonardo, I’m scared.

Leonardo

Ludovico Sforza is down there waiting for us. Come on !

Bartolomeo No, Maestro! Ask Zoroastro…

Leonardo

No ! (IC) you tested it and you must do it.

Bartolomeo

No, Maestro…

Leonardo

Dear Bartolomeo once you have tasted flight

you will walk forever with your eyes turned skywards, for there you have been and there you will always long to return.

It’s not known for certain if Leonardo ever used his parachute – his written notes are difficult to decipher, perhaps purposely.

And there are no physical remains of any of his inventions – no way to tell for sure if any of them passed beyond the idea stage.

But in 1482 he was in the service of Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, a warrior Prince interested in any invention with a military application.

Like swooping down on enemies encamped at the foot of a high cliff…

Duke Sforza

And what did you bring for us today, Maestro Leonardo?

Leonardo

Duke Sforza, my Lord, today I will demonstrate an ingenious apparatus by which a man can leap from any height without injury. It could be used to escape from a tower on fire.

Zoroastro

Now!

Bartolomeo Aaaaahhhhhh!

Cecilia

Look!

Bartolomeo Uh uh!

Duke Sforza

Maestro Leonardo, you always amaze us. How do you come up with such ideas?

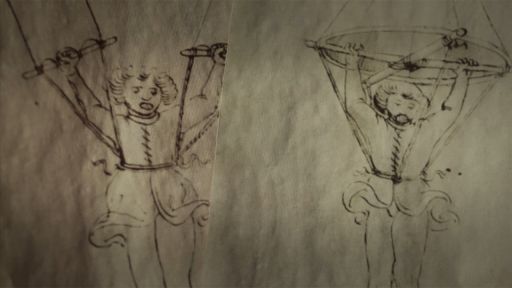

But did Leonardo really invent the parachute?

Alt:

In fact, Leonardo did not invent the parachute.

In 1968, researchers examining an obscure trove of Renaissance drawings discovered sketches from the studio of a 15th century Italian inventor that were eerily similar to Leonardo’s study for a parachute. The inventor: Mariano di Jacopo, known as Taccola.

Andrea Bernardoni – Historian Galileo Museum This drawing, the design for a parachute, is the oldest known to us and it is very similar to Leonardo’s. It was found in a manuscript conserved at the British Library in London. Leonardo knew manuscripts from the Sienese engineering tradition and he even refers to Taccola’s drawings in his manuscripts.

Andrea Bernardoni There are actually two drawings: the second is a flying man, without a parachute, although the subject is similar.

He is holding two sticks with two fabrics, like two wings. It is a much more primitive design that goes back about fifteen years before Leonardo's drawing.

Taccola was an engineer of the early Renaissance, 70 years older than Leonardo. He was among the first to use drawing as a design tool.

Before him, engineers worked out their inventions as they built them, through trial and error …

His manuscripts detail civil and military machines, some original, others are copies of ancient inventions.

And just as Leonardo copied him, Taccola’s idea is copied from a Muslim inventor, Abbas Ibn Firnas, who, the story goes, leapt from the minaret of the Cordoba mosque in 852, and suffered only minor injuries.

So why is Leonardo remembered as the inventor of the parachute?

Mario Taddei – Technical director Leonardo3 In the Codex Atlanticus notebook we find Leonardo’s parachute. But we know it’s not really his invention. He copied it from Taccola.

Mario Taddei The incredible thing is that Leonardo is the first to write about the material needed to make this object: cloth made of waxed flax, so that the air doesn't come through and it becomes waterproof, like the feathers of the birds.

For the first time, he describes how this object has to be built - he’s the only one to think about the dimensions.

There’s another interesting thing on this other part of the sheet. We find a lot more subjects. Leonardo wrote many pages about how to build a flying machine. And here we find five or six examples of them.

In these small sketches Leonardo shows himself not only as an artist, or an almost insane inventor . . .

Mario Taddei For the first time, we see Leonardo da Vinci, the scientist, and this is really amazing !

Leonardo copied dozens of Taccola’s inventions: the screwpump, a device to raise water

The life preserver – adapted by Taccola to float armored knights across rivers.

And the snorkel, though Leonardo’s version is more developed with floaters to ensure airflow and valves to counter water pressure. As with his design for the submarine, he relies on science, Taccola on fantasy.

Taccola died the year Leonardo was born, but he cast a long shadow. And was a powerful inspiration.

The young Leonardo encountered Taccola’s drawings in the course of his artistic apprenticeship – beginning in 1467, at 15 years old.

Andrea del Verrocchio Leonardo! Leonardo!

Master of the greatest of the dozens of artistic workshops in Florence, Andrea del Verrocchio challenged Leonardo, fired his passion and began the transformation of this uneducated country boy from the town of Vinci in rural Tuscany.

Charles Nicholl - biographer A small town or a large village where nature came right up to your door and your window. So he was immersed in natural forms.

So he was immersed in a landscape which one sees repeated over and over in his paintings and drawings. And I think perhaps the most profound legacy of his childhood was his supreme mental independence. And this independence of mind feeds on into Leonardo as a thinker. As a philosopher. As a scientist.

Leonardo’s father paid for his apprenticeship - even though he was born illegitimate. The idea was to provide him with a trade.

Under Verrocchio, he studied architecture, engineering and mechanics as well as painting.

All were considered art in the Renaissance – artists were trained as craftsmen, not intellectuals. He never had a formal education.

Charles Nicholl At the studio of Andrea del Verrocchio was… extraordinarily versatile and varied in its output. Paintings were certainly one of its major outputs, but only one. Verrocchio himself was primarily a sculptor. And, one has to think, really, of a sort of communal workspace, full of the smells and sounds of almost, one might say, light industry.

Fritjof Capra – historian of science The workshop of Verrocchio was not only a place where Leonardo learned all kinds of skills; it was also a place of intellectual excitements. For one thing, the master painters who had left the workshop came back to learn the newest techniques, to discuss the latest about oil painting. People like Botticelli, or Ghirlandaio, or Perugino, who were master painters would hang out with Verrocchio, come in the evenings to discuss the newest developments. So, Leonardo had the tremendous inspiration in all kinds of knowledge, and I think his tremendous scientific curiosity also may have been triggered in this workshop culture.

Andrea del Verrocchio Leonardo!

Leonardo Maestro!

Charles Nicholl His interest in machinery would have been considerably quickened in 1471, when he was probably part of the team of Verrocchio's studio, which was entrusted with the task of putting the copper orb right on the top of the lantern above the dome of Florence Cathedral. So, the technical problems of getting a 2-ton ball of copper up 300 metres to the top of Brunelleschi's dome required the use of some pretty complex and robust machinery. And it would seem to be at that point that Leonardo's interest in the work of Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect of the dome and the great engineer of the earlier Florentine Renaissance, takes shape.

For a long time Leonardo was credited with inventing the construction machines in his notebooks - but they are actually copies of Brunelleschi’s, invented 50 years earlier to raise the Duomo, and used again by Verrocchio.

Elizabeth Crouzet-Pavan

Historian of the Renaissance I think we have to insist on the fact that the Renaissance is also a Renaissance of machines, a technical Renaissance.

For example, in Florence the Dome of Brunelleschi was a highly technical achievement, which involved complex mathematical calculations . . . and many young students came to Florence to study the Dome.

In Verrocchio’s studio, Leonardo’s mind was forged by artists and architects who were transforming the world through their works and through the power of a new intellectual movement – Humanism.

Elizabeth Crouzet-Pavan

Humanism is a cultural movement that really takes form and gains power in the first three decades of the fifteenth century.

Humanists believed in a better future for humankind, in the potential for a better man…and perhaps this is the fundamental break with medieval culture, which was marked by a sort of fundamental pessimism.

Brunelleschi’s dome is one of the great achievements. To construct it, he studied the monumental ruins of classical antiquity, reviving long-forgotten building techniques.

The rediscovery of ancient Greece and Rome is the foundation of humanism.

In the Middle Ages, the ruins of Imperial Rome seemed a mystery. Centuries of invasions, plague and decay had erased the memory of Rome’s grandeur. Even Latin had fragmented into regional languages.

The long cultural chain leading from Greece to Rome was broken.

But in the 14th century, Florence saw a new class of merchants and bankers prosper as a result of international trade.

Worldly and secular, they were drawn to the glories of the classical world, paying fortunes for ancient manuscripts found in isolated monasteries and distant libraries.

In 1439, the most powerful family in Florence, the Medici, played host to the Byzantine Emperor and his court. Thirteen years later the emperor’s capital, Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Turks.

Greek scholars fled to Florence. Bringing manuscripts from the thousand-year-old Imperial library, they became teachers and translators.

The encounter between East and West kicked the fledgling Renaissance into high gear.

Elizabeth Crouzet-Pavan

It’s at this moment that the concept of the Middle Ages, the Dark Ages, is invented. And at the same time the concept of Renaissance, the return of the light, is born.

It’s the idea that for decades wisdom was somehow hidden from humans. But reading the ancients directly – rediscovered and newly translated texts unknown during the Middle Ages – gives the power to access this treasure of knowledge.

Suddenly they have direct access to the hidden understandings somehow lost over the last ten centuries.

Caught up in the Humanist fervour, Cosimo de’ Medici hired translators and scribes to copy every type of ancient manuscript: his goal was to create a universal library containing every written work.

Elizabeth Crouzet-Pavan

Cosimo de Medici invited a group of humanists to settle in his villa outside Florence, Villa Careggi.

They created an academy. A place where humanists would meet to talk, to play the lyre…

It was at heart a political program to increase the power of the Medici family. It starts with Cosimo and will continue, with his grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent.

Lorenzo de Medici was just 3 years older than Leonardo – but he was a product of an elite Humanist education.

Like his grandfather Cosimo, he was determined to advance Humanism, and with it, his family’s power and prestige, through the patronage of artists and scholars.

But for wealthy patrons and aristocratic Humanists, artists and engineers were little more than simple workmen.

A commission usually included a detailed description of the scene, the colours, the size of the painting – even the number of angels. There was little room for creativity.

Boy

The Medicis, the Medicis, Lorenzo is here!

Leonardo

Are you sure?

Boy

Absolutely sure!

Leonardo

Let’s go!

Charles Nicholl Lorenzo de' Medici , was a major client of the Verrocchio studio. But, the evidence that he supported Leonardo, seems to me pretty patchy. In fact, I'd say there was rather some opposite evidence to show that Lorenzo considered Leonardo… an unreliable sort of character.

Already, Leonardo had a reputation as distracted and irresponsible. He left paintings unfinished and abandoned commissions… even after being paid.

And it only got worse when, after 10 years of apprenticeship, he left Verrocchio and set out on his own in 1476.

Charles Nicholl It's a kind of obscure period in the biography. And, it's slightly clouded by… a couple of run-ins with the authorities in connection with his homosexuality. The officers of the night, as they were called - what we might call the vice squad - received a report about a certain young man and about other young men, or men, who frequented his company at night for immoral purposes, and Leonardo is one of the men on that list.

Charles Nicholl I have a feeling that Leonardo is experiencing some uncertainties, some self-doubt. He realizes the limits of his power. The limits of his status. He described himself as homo senza lettere, an unlettered man. He meant he hadn't had the sophisticated Latinate schooling.

Leonardo

Voice-off They will say that I, having no literary skill, cannot properly express that which I desire to treat of, but they do not know that my subjects are to be dealt with by experience rather than by words. Though I may not, like them, be able to quote other authors, I shall rely on that which is much greater and more worthy: on experience, the mistress of their masters.

Charles Nicholl Machiavelli has a line in one of his plays: “If you don’t have power in Florence, even the dogs won’t bother to bark at you”. And I think there’s probably a feeling with Leonardo, a sense of exclusion from the more sophisticated polished, intellectual world.

The only way to financial security for an artist was to find a patron – a prince willing to retain his services in his court.

Leonardo knew that Lorenzo De’ Medici would never support him. So, he looked elsewhere, to Milan, where the young Duke Ludovico Sforza was assembling artists and scholars to create a “New Athens”. And the Duke paid well.

Leonardo set out to draft a resume.

Leonardo

Voice-off My Most Illustrious Lord I beg leave to present myself to you and to discover to your Excellence my secrets of war. . .

I will make covered vehicles, safe and unassailable which will penetrate the enemy and their artillery and there’s no host of armed men so great that they would not break through it.

I have also types of cannon most convenient and easily portable with which to hurl small stones almost like a hail storm. And the smoke from the cannon will instil a great fear in the enemy on account of the grave damage and confusion.

Where the use of the cannon is impracticable, I will install catapults, mangonels, trebuchets and other instruments of wonderful efficiency not in general use.

For two centuries, the Italian peninsula had been torn by nearly constant warfare - the Papal States, Venice, Milan, Florence and Naples all vied for dominance. Sometimes allied with outside powers.

Leonardo had never seen war - but he knew the labor market: military engineers were in high demand.

Still, he adds a footnote…

Leonardo voice off What’s more I’m a sculptor. I can execute figures in bronze, marble and clay. Likewise in painting, I can do everything possible as well as any other, whosoever he may be. I’m the man you need .

Mario Taddei In the Codex Atlanticus there is something very strange. A resume, the first resume in history, made by Leonardo da Vinci. But Leonardo introduces himself as a military engineer, who makes secret weapons, incredible submarines, assault bridges . . .

Leonardo is lying. Why is he lying? He’s still young and comes from Verrocchio’s studio, how could he be such an expert in military engineering? He is not.

But here is his genius: Leonardo is not stupid. He does what any intelligent person would do: he studies, he studies a lot.

Mario Taddei This is Roberto Valturio’s book, printed just before Leonardo leaves for Milan. Leonardo uses it as a source; it is an encyclopedia of military weapons.

We see Leonardo’s famous scythed chariots, taken from this book. Leonardo is inspired by this book, he studies every single page and copies all these machines and gives them to the Duke, as his own inventions.

Here we see something beautiful, perhaps the ancestor of Leonardo’s tank, it is an armoured tank, with guns. One can hide cannons inside.

Printed in 1472, Roberto Valturio’s “On the Military Arts” was among the first illustrated printed books. Leonardo turned to it not out of curiosity – but desperation. He needed to sell himself to the Duke of Milan.

But his improvements on Valturio led to some of his most famous inventions: combat wagons, siege machines, even a machine gun . . .

Mario Taddei This is a spheroidal machine gun. Leonardo understood that just having many cannons is not enough. If your enemy can run fast, or even fly, this machine gives you the power to chase him from left to right, but one can also move it like a modern gun.

Thanks to the central sphere inside the gun, one can follow the enemy even if he is moving. It’s a fantastic machine, it could even work today. We rebuilt it for the first time, with its original dimensions, just like Leonardo conceived it.

Charles Nicholl When Leonardo arrived in Milan, in the spring of 1482, he found a city much bigger than Florence. Much less like a town, and more like a metropolis. He also found a very cosmopolitan city. There were a lot of influences percolating down from across the Alps. So, something of a crossroads of trade, and therefore also, of ideas and techniques.

The spirit of the city was dynamic, entrepreneurial, practical -

Milan suited Leonardo - and though the Duke did not immediately hire him as military engineer, Leonardo set up a studio for painting.

C. Nicholl Leonardo’s first commission from the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, was a portrait of Ludovico's mistress, Cecilia Gallerani. A wonderful portrait known as The Lady with an Ermine. It's full of life and movement. Full of vitality. Full of that wonderful movement of the—of the sitter towards the painter as if momentarily capturing her about to speak. That way Leonardo has of capturing women in particular—in a moment of suspended or potential animation.

In Milan, Leonardo found a fresh atmosphere that sparked his curiosity. And he found new inspiration in the scientific spirit of the universities and booming book trade.

The printing press was invented about the time Leonardo was born. It was a communications revolution – like the internet today.

In just 30 years, more books were printed than had been copied in all the Middle Ages. The cost of a book dropped by 80 percent.

Books opened a new world for Leonardo – he could read the ancients directly - a source of inspiration that would ignite his scientific impulse.

Fritjof Capra These advances of humanist science and philosophy would not have been possible without this tremendous technological breakthrough, the invention of printing. In fact, there were two inventions that contributed: one was the movable-type typography, and the other one is, was engraving, where you could present pictures in a way that could be multiplied infinitely without deteriorating. And so, this had two consequences. Dissemination was much more rapid, and it was much more precise.

Book- keeper Could you be interested in this book?

Leonardo

For sure!

Fritjof Capra When he arrived in Milan, he had no books. Not a single book, at the age of 30. Eight years later, he had about 35 books, and another I don’t know, 10 years later, he had about 200 books. These were books of science and philosophy, the classical books about mathematics, botany, astronomy, anatomy and so on. So he had the books of a Renaissance scholar, and he actually became a Renaissance scholar.

Leonardo …amat…amabam, amabas. Amo, amas, amat, amamus, amatis, ama…

But the untutored Leonardo needed Latin – at the age of 35 he began memorizing verbs like a schoolboy.

Zoroastro – court mechanic and magician – came from Florence to assist Leonardo who was finally appointed Ducal engineer—responsible for everything from canal building to staging royal entertainments.

Leonardo finds new colleagues attracted to the dynamic city and the free-spending Duke, men determined to reinvent themselves and their society.

Luca Pacioli, Leonardo’s tutor in mathematics whose book, “The Divine Proportion,” was illustrated by Leonardo…

Francesco di Giorgio Martini, the most celebrated military architect of his time and source for some of Leonardo’s war machines.

Donato Bramante, painter turned architect. He brought the high Renaissance style to Milan and would go on to design St Peter’s in Rome.

His ironic fresco, Heraclitus and Democritus, is a double portrait of himself and his friend Leonardo – the only image of Leonardo from the period.

Charles Nicholl He's an opportunist in many ways, Leonardo. He learns what he needs to learn for a particular purpose and for a particular situation. And his situation as sort of, as it were, entertainments manager for the Milanese court, might not seem that congenial, put in those terms, but it did enable him to channel all sorts of interests, technical, scientific, engineering interests, as well as the pictorial, a sort of poetic interests that he has as an artist.

For the men and women of the Renaissance, there was little difference between technology and magic.

Seemingly controlled by unknown forces and hidden powers, Leonardo’s spectacles filled people with curiosity and wonder,

He went so far as to invent a prototype robot just for the Duke’s entertainment.

Mario Taddei Leonardo is said to have invented the car, but it’s not a car. He studied in Verrocchio’s studio where in addition to paintings and sculptures they made theatrical objects and this is probably a magical theatrical device.

Leonardo’s robot.

Mario Taddei Why a robot? Because it is programmable. Leonardo invented these systems: these simple rods already existed, but Leonardo conceived them as something new.

If I put these rods in this position - one, none or many - these two levers will touch the petals from time to time and the cart will move from right to left.

For the first time he creates a robot with its own internal energy, a robot that does what Leonardo wants it to do.

Mario Taddei This is a dream that takes us back to Leonardo’s predecessors. People like Heron of Alexandria, who created magic objects for the fun and wonder of making things that never existed before.

Leonardo’s robots copy inventions made 1000 years earlier, during a Greek scientific revolution in Alexandria. There, the 1st century engineer Heron compiled a book of temple magic including doors that open when a fire is lit, the world’s first vending machine – for holy water – and even a self-propelled cart.

Leonardo had a summary of Heron in his library.

The 12th century Arab Golden Age preserved and advanced the science of Alexandria. Inventor and engineer Ibn Al-Jazari updated Heron with Indian and Chinese technologies encountered with the spread of Islam. His ingenious clockworks and automatons used control devices like those in Leonardo’s cart.

Advanced Arab scientific works on mechanics, astronomy, mathematics and optics made their way Europe through Muslim Spain, or through Medici agents sent to Persia and Syria in search of manuscripts.

Salim Al-Hassani

Professor of mechanical engineering Leonardo had actually referred to the book of optics by Alhazen al-Haytham. Now he is a guy who faced two theoretical explanations of how we see and what he did is he carried out experiments to verify what he thought how we see and developed what we call the dark room or dark box which became the pinhole camera and then we referred to it as the camera obscura. Now, he says that you should always doubt what you read even you have to doubt yourself but you must prove things by experiments so experimentation began to take a lot of interest in that society.

Leonardo’s notes on reflection show he was familiar with Al-Haytham’s Optics, written in 1021 – it’s the source of his interest in the camera obscura, a model of the eye, where a small hole acts as a lens to project a brightly lit exterior on the opposite wall in a darkened room.

Leonardo was not a prophet of the future – he discovered a distant past where a much more advanced technology had existed, lost to the West with the fall of Rome.

Leonardo

Ibn al-Haytham arranged three candles in a row in a dark room. He put a screen with a small hole between the candles and the wall…and noted that images were formed.

Fritjof Capra Leonardo certainly was very influenced by Arabic scholars. His experimental method, his empirical method, somehow came from his reading of these texts, because these Arab scholars were not bound by religious doctrine. Islam left them complete freedom to do their science, their philosophy, their reinterpretations of Aristotle.

In reinventing an ancient technology, Leonardo also reinvented something that had been lost for centuries: the scientific experiment.

His detailed observations and carefully-drawn results paved the way for modern research methods.

Charles Nicholl Books start to mean something to him and it’s hard to know exactly what this change of attitude signals, but I suppose it’s the desire to… he goes with that newly encyclopedic idea that Leonardo has himself. But all branches of knowledge are within his reach and that he - as what he calls the “painter philosopher” - must acquire knowledge of all sources. And indeed there is a kind of bewildering multiplication of his interests around about the same time as he starts to acquire and collect books.

Leonardo voice off Although nature begins with reason and ends with experience we must do the opposite: to begin with experience and from this to investigate the reason.

In 1482, a translation of Ptolemy was printed from a newly discovered Greek manuscript. The second century mathematician created the earth-centred model of the universe held by Alexandria, Islam and Europe for over 1,200 years.

Leonardo turned his attention to the geometry of the night.

Ptolemy held that the moon and planets shine with their own light.

As a test, Leonardo embarked on an imaginary voyage – he placed himself outside the earth.

He realized that moonlight is really reflected sunlight.

And that the dim light that makes the body of the moon just visible at crescent is reflected from the earth: earthshine.

Leonardo voice off Any one standing on the moon, when it and the sun are both beneath us, would see our earth and the element of water upon it just as we see the moon, and the earth would light it as the moon lights us.

The earth is not in the centre of the Sun's orbit nor at the centre of the universe, but in the centre of its

companion elements, and united with them.

“The Sun does not move.” A cryptic phrase, written 100 years before Galileo. But never developed further in his notebooks. A theory of the heavens? Notes for a spectacle? Impossible to say.

Leonardo believed that the same force that moved the heavens moved the body: as above, so below. The form of the cosmos was reflected in the human form.

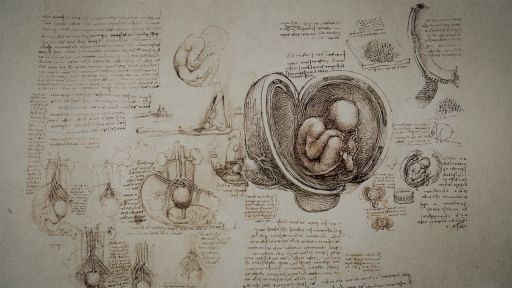

And just as the map of the heavens went unchanged for centuries, so too did the map of the body. Doctors relied on illustrations inherited from ancient Greek and Persian sources.

Leonardo would conduct his own medical examinations.

Charles Nicholl First sign of Leonardo's actual practical involvement in anatomy and dissection is some wonderful, slightly eerie drawings of a skull, dateable to about 1489. One of the drawings makes it clear that at least one of his interests is to establish by a sort of grid-referencing, the particular location of the “sensus communis”, which is an Aristotelian concept, the communal sense where all the sensory impressions go into the brain and which, was where a man's soul could be found.

Leonardo’s first dissections were in search of the soul.

His guide: a newly published manual of anatomy by Mondino de Liuzzi, which would remain the authority for 250 years.

Fritjof Capra Even though he was a mechanical genius, he never treated the body as a machine. He said that nature has given the body, or has given animals, mechanical instruments. But the source of the movement comes from the soul, which is not mechanical, which is spiritual, and by that he meant immaterial, and he actually traced back the sensory nerves to the centre of the brain, which he considered to be the seat of the soul.

In the centre of the brain, he found three small cavities – the ventricles of the brain. The site, he was certain, of Aristotle’s sensus communis.

Zoroastro …et ex consequenti in ventriculis eius. Substantia eius est substantia medullaris frigida et humida…

Leonardo voice off The soul appears to reside in the judicial part and the judicial part seems to be the place where all the senses come together, the sensus communis . . . and the sensus communis is the seat of the soul.

Zoroastro In medio vero huius est sensus communis…

While Leonardo’s proof of Aristotle’s theories has not stood the test of time, his anatomical drawings have never been surpassed. Sequential views suggest a cinema animation.

And views from multiple angles provide a true three-dimensional understanding of the body’s form.

His images are never static but animated by a dynamic energy, and seem just on the verge of moving on their own.

Leonardo’s illustrations, as precise as his technical drawings of machines, were unequalled in accuracy until the photographic techniques of the 19th century.

But they were never published in his lifetime. They remained unknown and unpublished for more than 300 years.

Fritjof Capra Leonardo, like his fellow humanists, was very eager to read classical texts. But there was a big difference: he would examine them in the light of his observation of nature, in the light of his own experience, and he would never hesitate to correct the classical texts, even of the greatest authorities.

When he made progress in one area, he immediately applied it to a related area. So that you can actually see his progress as a kind of spiral that goes higher and higher but always touches several fields.

Dealing with a problem or understanding a phenomenon for him meant to see how it is related to other phenomena. In this way, I think, he generated what we now call the scientific method, and he singlehandedly created the scientific method.

Leonardo wanted to understand underlying principles.

Just his study of spirals – in water, flights of birds, plant growth, even hair patterns – led him to explore the fields of geology, botany, topology and more.

For him, everything was deeply connected: a great system, in continual movement, with human beings at its center.

And there is an image that seems to summarize all of his work: the “Vitruvian Man.”

Toby Lester – author of “Da Vinci’s Ghost” Everybody knows this picture, it’s become a kind of icon, even like an emblem of the human spirit. Leonardo drew it in about 1490… and he did it as a kind of answer to a riddle.

The architect Vitruvius from ancient Rome had proposed that a man could fit inside a square and inside a circle and for centuries after that people had wondered how that might work at a literal and at a metaphorical level.

Zoroastro

Four cubits equal the height of a man.

Vitruvius’ long-forgotten book, printed in 1486, stated that to achieve beauty and harmony, buildings must reflect ideal human proportions. Before scientific standards, all measurements were taken from the body – the foot, the digit, the step . . .

But to build something, the proportions must be known – how many thumbs in a palm? How many palms to a step?

Architects hoped to find the answer in Vitruvius’ ideal proportions, unlocking secrets of ancient buildings.

Zoroastro

Forty at the dial. Nineteen at the rod.

But the book wasn’t illustrated. How could a human body fit proportionally inside a circle and a square?

The image of a human at the centre of a circle is an ancient way of relating individual existence to the infinite universe.

It proposes a linking between the two: the individual is a microcosmos – a miniature reflection, in all its parts, of the universe or macrocosm.

As above – so below.

Vitruvius’ square represents the material world – his figure has a dual nature, inscribed in both the heavens and the earth.

His idea was appealing to Humanists values.

But without illustrations, the question remained: How

to fit the body in a square and a circle without distorting its proportions, became an obsession for 15th century architects. Those who tried failed.

Leonardo was fascinated with proportion.

During the Renaissance, the goal of art was the expression of harmony, and harmony is a matter of proportion.

Vitruvius gave complex measurements for the ideal body – but Leonardo did his own. He needed to verify everything for himself.

And then he, too, undertook the quest for Vitruvian Man.

Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara It’s a matter of proportions. Come, I want to show you my work.

In 1490, Leonardo met a young architect, also hard at work on the Vitruvius problem.

Toby Lester A discovery recently suggests that there was another person who also drew a Vitruvian Man. It comes in a manuscript by an architect named Giacomo Andrea who was from Ferrara, but who worked in Milan at the time that Leonardo was there, and it turns out the two of them were good friends.

Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara Look at this!

Leonardo

I have all the measures inside me. The divine ones as well as the ones coming from earth and hell.

Giacomo Andrea da Ferrara You see, the Man is called “little world”, who contains in himself all the general perfections of the entire world.

Toby Lester If you look at this manuscript of Giacomo Andrea, which seems to date to around 1490 as well, possibly a little bit earlier, you’ll find in it a vision of Vitruvian Man that is eerily like Leonardo’s and seems to be a predecessor. It’s a tentative effort that you can see erasures on. You can superimpose them and get almost an identical image.

Again, Leonardo’s image doesn’t appear out of the blue. It’s part of a progression, and it may have been part of a very close collaboration with Giacomo Andrea.

Giacomo Andrea decentered the circle and the square: the spiritual realm of the circle is centered on the navel, the earthly realm of the square on the genitals. No one else had thought to do that.

The same solution is found in Leonardo’s famous drawing, but, as always, he takes it much further.

Andrea’s figure is almost Christ-like, a throwback to the Middle Ages – Leonardo’s is unquestionably human, bold and ambitious.

Vitruvian Man is a pure expression of the Renaissance – a secular, almost carnal figure whose reach extends to the very limit of the cosmos.

And whose face, staring out with absolute confidence, might be that of Leonardo himself, at 38 years old and at the height of his powers.

Charles Nicholl There seems to be some arrogance in the idea that he is putting his own face, into this central iconic sort of figure. I think it is appropriate though because who better to encapsulate this knowledge that he is imparting, than the painter, philosopher, anatomist, Leonardo da Vinci, who finds all these different avenues to his knowledge of the human condition, of what it is to be a man.

Leonardo’s great dream was to write a book, a series of books, which would unify and transmit the vision he developed over years of research.

That, for him, would cement his posterity in a way his fragile paintings could not. He would join the timeless human chorus of the book.

There would be a manual of painting, a detailed book of anatomy, a book of mathematics, astronomy, geometry . . .

But he never really seemed able to stop and look backwards. New subjects called to him – the movement of water deluges the flight of birds. This project, like so many, went unrealized.

Leonardo was the perfect man for his time and his time was perfect for him.

Leonardo was opposed to any kind of imitation: if he copied the work of others it was to learn from it, transform it, enhance it, and send it forward to us as a great gift.

Leonardo voice off Human ingenuity will never discover an invention more beautiful, easier or more economical than nature’s, because in her inventions nothing is wanting and nothing is superfluous.