It is impossible to know what drew the first Neolithic people five millennia ago to the grassy Salisbury plain that would eventually house Stonehenge. Remove the stones, the earthen works, the history, and the site becomes just another field. And yet once the first ditch and earthen bank were built 5000 years ago, Stonehenge became something — something that drew people there, to build, to modify, to reinvent the site — although archeologists don’t know what that first something was.

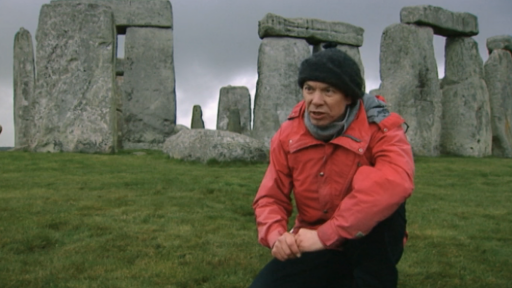

By the time the first megaliths were put up, however, Stonehenge had become a site of ritual importance to the local population. Most likely, the rituals involved death. In fact, before the megaliths were added, Stonehenge was used as a cremation cemetery; hundreds of bodies were buried there. That suggests, says archeologist and Stonehenge expert Mike Pitts, that “in the very early years of Stonehenge there was a very strong association with the disposal of the dead and ceremonies involving the dead.”

By the time the first megaliths were put up, however, Stonehenge had become a site of ritual importance to the local population. Most likely, the rituals involved death. In fact, before the megaliths were added, Stonehenge was used as a cremation cemetery; hundreds of bodies were buried there. That suggests, says archeologist and Stonehenge expert Mike Pitts, that “in the very early years of Stonehenge there was a very strong association with the disposal of the dead and ceremonies involving the dead.”

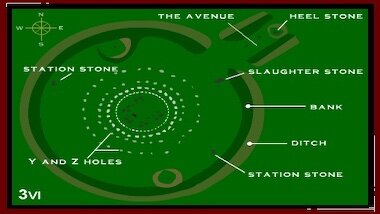

After the bluestones and sarsen stones were added some 4,000 years ago, the connection with death continued, although archeologists can’t be exactly sure how the site was used and what it meant to the local people. “At the end of the day we are just guessing, because this is thousands of years before people are writing anything down, but there are a number of clues,” says Pitts. One of the most obvious — and most often misinterpreted — clues is the orientation of the stone monuments to the midsummer sunrise, on the northeastern side, and to the midwinter sunset on the southwestern side. “There was clearly something deliberate there. People have all sorts of ideas about what this adds up to, what it means,” says Pitts, including theories that the stones represent some sort of astronomical calendar or a mathematical computer. Those theories have no merit, Pitts says. “You’ll find very few archeologists who agree with that. The alignment is very much a symbolic one rather than a scientific one, in the same way that Christian churches are aligned east/west, which is approximately sunrise/sunset. That is symbolic — so symbolic that people have forgotten why it is there.”

Another clue is that at the same time that the megaliths were added to Stonehenge, another massive circle was being constructed a few miles to the east — only in this case, of wood. “Wood is a material that is alive, and stone is dead,” says Pitts, “so let’s just suppose that the wooden sites are places where people go for ceremonies when they are alive, and perhaps where people who are dead are thought of in some transitional form.” After some time, the spirit of that person would move to Stonehenge to join the ancestors in the world of the dead. The stones themselves might have represented those ancestors. “Maybe this happens in some particular way at midsummer,” he says, “when the worlds of the living and dead and ancestors are tied up with the movement of the sun and perhaps the moon.”

Another clue is that at the same time that the megaliths were added to Stonehenge, another massive circle was being constructed a few miles to the east — only in this case, of wood. “Wood is a material that is alive, and stone is dead,” says Pitts, “so let’s just suppose that the wooden sites are places where people go for ceremonies when they are alive, and perhaps where people who are dead are thought of in some transitional form.” After some time, the spirit of that person would move to Stonehenge to join the ancestors in the world of the dead. The stones themselves might have represented those ancestors. “Maybe this happens in some particular way at midsummer,” he says, “when the worlds of the living and dead and ancestors are tied up with the movement of the sun and perhaps the moon.”

Many of the massive stones had already begun to fall down by 1500 BC. Until the rediscovery and analysis of skeleton number 4.10.4, the Anglo-Saxon man beheaded and unceremoniously buried at Stonehenge, archeologists had no clues about what significance the monument might have had between the last construction there and the 19th century A.D.. “We somehow imagined that Stonehenge was barely noticed during that time,” says Pitts (although references do exist to the monument, including a medieval story that it was the burial place of a legendary king).

“When we identified this execution as an Anglo-Saxon event, it changed everything.” Although the word “stonehenge” means “stone gallows” in early English, archeological evidence indicates that executions were not normally conducted there in Anglo-Saxon times. “So there was something exceptional about this event, that could have been quite powerfully frightening and mythologically very important. The feelings these people had toward Stonehenge at that time, not least the poor bloke who had his head cut off, were obviously very real and significant, and until now we had no idea at all.”