TRANSCRIPT

♪♪ -Two million, five hundred thousand rivets... and 18,000 pieces of metal... all painstakingly assembled.

♪♪ [ Whirring ] An engineer built the Eiffel Tower... chasing an unimaginable height -- 1,000 feet.

Despite attempts around the world, no building had ever grown so tall.

But the announcement that Paris would host the 1889 World's Fair set in motion a competition between two men to build something unprecedented.

Gustave Eiffel's main competition was renowned architect Jules Bourdais.

Ultimately, Eiffel's tower of iron prevailed while Bourdais and his stone structure have become footnotes in history.

The competition between the two men was fierce... and represented a much larger struggle gripping France at the time.

Traditionalists resisted new styles, materials, and techniques, denying progress in art and architecture.

Stone against metal... art or industry... tradition versus progress.

Who would build the tallest structure?

As the 19th century came to an end, new technology fueled humankind's dreams of building larger, better, and taller.

At the heart of this rivalry between Bourdais and Eiffel was the inevitable march of progress... and change is never easy.

♪♪ -Monsieur Bourdais!

Monsieur Bourdais!

-On the morning of May 31, 1884, Paris was in an uproar.

-Papa!

-[ Speaking French ] -News had broken that the city would be host to the 1889 World's Fair and would need a symbolic monument.

Architect Jules Bourdais and engineer Amédée Sébillot had already patented a design for a stone tower.

They hoped this would be their chance to make it real.

In his workshop a few miles away, engineer Gustave Eiffel was less enthusiastic.

-[ Speaking French ] -He was very busy.

His company already had too many projects to complete.

-[ Speaking French ] -Still five years away, the event would mark the French Revolution's centennial, and Gustave Eiffel knew that this was an opportunity he couldn't pass up.

He wouldn't miss an event of this importance.

-The World's Fairs in the 19th century were absolutely extraordinarily huge celebrations of industrial progress, economic progress, human progress, even.

Often there was a retrospective element to show how far humanity had evolved over centuries and millennia.

And there was a huge amount of competition, as well -- competition to show off who was really ahead -- we might call it -- in the -- not the arms race, but the "progress race," perhaps.

[ Indistinct conversations ] -The grand exhibition was an opportunity for France to show off its accomplishments and innovations.

♪♪ And underscoring the entire event would be the country's transformation into a modern republic.

♪♪ -[ Speaking French ] -The aim of this World's Fair was to demonstrate the link between France's scientific and technological development... and the great principles of 1889 -- liberty, equality, and fraternity.

So it was liberty guiding the world politically, but also guiding the world in terms of innovation, the scientific spirit, and so on.

-The fair would demonstrate that political freedom fostered advances in other areas, like science and technology.

New inventions and products were often introduced to the public at these international exhibitions.

In 1854, in New York, American Elisha Otis presented his elevator.

He even cut the elevator cable in public to demonstrate its safety system.

Two decades later, Alexander Graham Bell debuted a strange device in Philadelphia -- the telephone.

-[ Speaking French ] -The World's Fair was a sounding board that could be likened to a constantly updated synthesis of the world's progress and destiny.

And, of course, architecture played a central role, in that it is itself a means of building the world.

-This time, to illustrate progress, the host country needed to present an exceptional building.

♪♪ The English had stunned visitors with London's Crystal Palace 30 years earlier at the very first World's Fair.

♪♪ ♪♪ Paris would need something as impressive.

For the 1889 fair, the hope was for something that would reach new heights.

♪♪ -The feat of reaching 1,000 feet, or 300 meters -- it's true -- gradually took hold over the course of the 19th century, culminating in the Paris World's Fair of 1889.

-[ Speaking French ] -It was like a major challenge that was thrown down from country to country.

Which country would be the first to build a 1,000-foot tower?

♪♪ -Constantly striving to build higher has always been part of human existence.

♪♪ In 2570 BCE, the Egyptians built the 475-foot-tall Cheops Pyramid.

This colossal work had only been surpassed by a few cathedral spires in the centuries since.

But the Industrial Revolution made new feats of daring construction possible.

♪♪ [ Iron clanging ] -[ Speaking French ] -Iron had been used for a long time as a reinforcement in construction, for example in cathedrals or classical architecture.

But these materials were produced in small quantities.

The revolution, the Industrial Revolution, would be able to produce iron in much larger quantities.

-In fact, it was easy to use.

It was less costly than masonry, easy to machine, and easy to install, since it involved assembly techniques.

-It has tensile strength.

It has compression resistance.

It is flexible, workable, and it can be drilled.

By way of comparison, a metal, cast-iron, or iron column only needs a diameter of around 4 inches.

It's the equivalent of a granite masonry column 20 inches per side, so it's much more resistant, and this would enable us to build things we'd never seen before.

[ Sea birds crying ] [ Ship horn blares ] ♪♪ -An Englishman first imagined a 1,000-foot tower in 1832, more than 50 years earlier.

Engineer Richard Trevithick invented the high-pressure steam engine and the first rail locomotive.

And he knew that the biggest challenge facing a building of this height would be wind resistance.

For his "Reform Tower," he designed a structure of openwork, cast-iron modules bolted together.

The center housed what would soon be called an elevator... propelled through a long tube by pressurized steam.

♪♪ Trevithick could have been the first to build a structure 1,000 feet tall... but he died of pneumonia just as his designs were completed.

♪♪ 20 years later, another Englishman, architect Charles Burton, took up the challenge.

As the gigantic Crystal Palace was being dismantled, he suggested repurposing the glass and metalwork to create a 1,000-foot tower.

♪♪ A metal frame of mutually reinforcing beams would hold the glass panes in place as the tower grew thinner with height.

♪♪ Charles Burton would have been responsible for the forerunner of glass skyscrapers... but the architect never convinced developers that his project had merit.

[ Indistinct conversations ] [ Birds chirping ] For the Philadelphia Exhibition in 1876, the Clarke and Reeves Company designed the Centennial Tower to celebrate American independence.

As iron producers and bridge builders, Clarke and Reeves designed a 1,000-foot tower to showcase their own work.

♪♪ The project featured a metal tube structure, which offered little wind resistance.

And a column in the center housed four elevators to take visitors to the top of the tower.

-[ Speaking French ] -Clarke and Reeves' 1,000-foot tower project was quite credible.

They used proven technology and had already built many bridges and structures using this technique.

-But Clarke and Reeves never raised the money they needed... and, ultimately, abandoned their dream of being the first in the world to complete a 1,000-foot tower.

And so the pursuit to reach new heights continued.

-With the circulation of information via the trade papers, information about what was happening in England and what might have been happening in the United States was quickly known.

The idea was gradually maturing to meet the height challenge.

-Many people in the scientific, political, diplomatic, and other spheres were keen for France to take up this challenge.

So the 1,000-foot tower had become a political issue, a war horse for France.

[ Horse hooves clopping ] -Could a Frenchman succeed where the British and Americans had failed?

Jules Bourdais was already responsible for one of Paris's most famous buildings -- the Palais du Trocadéro.

♪♪ It stood at the top of a hill on the site of today's Palais de Chaillot.

Bourdais designed the innovative work with architect Gabriel Davioud for the 1878 Exposition.

Flanked by two 260-foot towers, it was a gigantic building with a 4,600-seat concert hall.

-[ Speaking French ] -The great attraction of the Trocadéro Palace was the elevators.

At the time, there was no other place where you could see Paris from such a height.

As simple as that.

-The construction of this palace made Bourdais a celebrity.

-He was rewarded and showered with honors.

And he was known not only in France, but internationally.

-And the orders poured in for Bourdais.

The press articles.

He was acclaimed everywhere.

-So not only was he well-connected, he was also linked to a number of important families and even major financiers.

So he was someone very prominent and well-placed in high society.

-Now Jules Bourdais wanted to be the first to reach 1,000 feet.

When the World's Fair was announced, he already had a design ready for construction.

He envisioned a stone tower, topped by a lighthouse, that would light up the city of Paris at night.

Gustave Eiffel must have been aware that Bourdais was attempting to reach 1,000 feet and, as an engineer, was surely intrigued by the challenge.

At 25, he had secured his first record by overseeing the construction of Europe's longest bridge, the 1,600-foot Bordeaux Bridge.

-He founded his own company at the age of 32.

He developed it.

He became a builder in the truest sense of the word.

And so he acquired great expertise in this field.

He'd had some outstanding achievements which had made headlines for their inventiveness and innovation.

-From Budapest's railway station to Porto's majestic Maria Pia Bridge, Eiffel had already produced several major works.

And while less well-known at the time than Jules Bourdais, he was considered a pioneer.

-Gustave Eiffel was probably one of the best at this time, since he implemented a strategy of assembling metal components.

He incorporated a certain number of parameters, such as fire resistance, but also wind resistance, which meant that he was soon able to build high structures.

-But Eiffel already had his hands full... -[ Speaking French ] -He was busy completing the Garabit viaduct in the heart of the Massif Central.

The railway span, with a height of 400 feet and a central arch 540 feet across, is still in use today.

♪♪ At the same time, the engineer was also finishing the framework for the Statue of Liberty.

Lady Liberty, a gift from France to the United States, was a relatively small job for Eiffel, but its construction in the heart of the capital was a brilliant advertisement for his company.

For Gustave Eiffel, building a 1,000-foot tower would be a crowning achievement.

But someone else produced the tower's initial design.

[ Conversing in French ] -On June 7, 1884, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, two of Eiffel's main collaborators, presented him with a drawing.

-This is a sketch that has been preserved for us, of a pylon.

You could say an extrapolation of a bridge pylon.

But instead of being 50 meters long, it was 300 meters long, and had a rather characteristic curved shape.

It wasn't a pyramidal pylon.

It had this curvature that was really characteristic of the tower that was part of this project.

The project was called a pylon.

It was not a tower yet.

Just a pylon.

A bit free like an antenna could be, but 300 meters high.

-Iconic Parisian buildings were superimposed over the sketch to give an idea of the scale.

-Of course, the two engineers didn't just make a little sketch.

They also drew up a brief calculation note to check the overall weight of the tower, taking into account the wind load and therefore the shape.

-The calculations were extremely accurate, so the possibility of reaching 1,000 feet was real.

The challenge of wind resistance seemed to have been solved, too.

The collaborators offered the drawings and calculations to Gustave Eiffel... but he remained unconvinced.

-So that's how it went at first.

Eiffel's reaction wasn't necessarily immediately enthusiastic.

-But he was intrigued and asked them to continue their exploration of the tower's potential.

-Koechlin and Nouguier were clever enough.

They found an architect, Stephen Sauvestre, whom they knew and with whom the company had already worked, and Sauvestre produced another design.

He even completely redrew the project.

Sauvestre added three very important things.

Firstly, he said that a pylon was fine, but a tower that could be climbed was better, because the public would be able to access it.

And Sauvestre envisioned rooms on the first and second floors that could accommodate the public.

And so he was going to give meaning to this project, the meaning of welcoming the public and therefore also of discovering, from the top of this tower, the landscape of Paris.

-With these improvements, Eiffel enthusiastically agreed to move ahead.

-He also gave the tower a more architectural form.

In particular, he designed four large arches to frame the pillars, giving the tower a kind of solidity.

And then he introduced ornamentation, a treatment of the top, even in his early sketches, even small statues.

Finally, he would give it a friendlier feel, more receptive to the public.

All of a sudden, we had a real project, a technical project designed by the engineers, an architectural project designed by Sauvestre, which became not only credible but attractive, and that's when Eiffel changed his mind.

-He had the opportunity to create something that had never been built before.

Like Jules Bourdais, Eiffel wanted to be the first to build a 1,000-foot tower.

This was the beginning of a tense competition between two men with radically different visions.

But they had started at the same place and knew each other well.

They attended one of the top engineering schools two years apart.

After the Ecole Centrale de Paris, their careers went in different directions.

Eiffel became the pioneering engineer... while Bourdais joined the world of architects advocating for traditional academic design.

Their paths occasionally crossed, as they had at the previous Paris World's Fair in 1878.

Bourdais built the Palais du Trocadéro, the highlight of that exhibition.

Eiffel was the engineer in charge of the City Pavilion, the Paris Gas Company Pavilion, and the facade of the fair's main building.

His work earned him the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur, or Knight of the Legion of Honor, and the congratulations of Bourdais himself.

-[ Speaking French ] -But there could be only one winner in the race to build a 1,000-foot tower.

Bourdais was confident in his design.

He'd been working on it for two years, and he was well-connected to high-ranking politicians.

Eiffel knew he wasn't starting out as the favorite.

To catch Bourdais off guard, he launched a press battle.

On October 22, 1884, an article in Le Figaro newspaper mentioned an extraordinary project for a 1,000-foot tower made of iron.

The mention was just enough to arouse curiosity.

And the next month, a more substantial article appeared in the scientific journal Nature.

This one had illustrations.

From the beginning, Eiffel's team believed that iron was the only material capable of withstanding the wind.

The article also highlighted the proposed tower's usefulness.

It would enable strategic observations during wartime, communications by optical telegraphy, and both meteorological and astronomical observations.

But perhaps most astonishing was the promise of electrical high-bay lighting, "as done in some American cities."

Bourdais had to react quickly.

A few days later, a new article presented his colossal tower of stone, with a base that was already as high as Notre Dame cathedral.

The tower itself was adorned with colonnades, and the center was reserved for elevator traffic.

At its summit, Bourdais included a large observation platform for 1,000 people at a time, as well as a system to illuminate the city.

-There was going to be an ultra-powerful beacon above people's heads, bringing light to all the streets in Paris.

For the general public, it was fantastic.

You have to realize they were living through the electricity revolution.

-It was only 1880.

The incandescent lamp had just been invented, and public lighting was still gas-powered, which meant it was fairly dim.

So electricity brought incredible comfort.

And Jules Bourdais and Amédée Sébillot wanted to bring this comfort not only to the streets, but also to people's homes.

-Part of the original project included reflectors that would redirect the rays from the lighthouse to hidden areas such as dark streets and inside apartments.

-And a man could read his newspaper at the window quite easily.

So there was this idea that not only could we bring electricity to the streets, but that we'd also somehow bring it into the home.

-But Bourdais didn't stop there.

Piqued by the competition with Eiffel, he went even further.

In December 1884, the plans for his tower topped 1,000 feet.

-It had become a tower described as ultra-gigantic.

370 meters high, six times the height of the Notre Dame towers.

-The two-tower war between Bourdais and Eiffel was taking shape, and soon the competition captivated the citizens of Paris.

The designs themselves represented two very different visions for the future -- on one side, tradition... and on the other, innovation.

Bourdais's tower, built of stone and with colonnades, reflected the academic approach, as taught at the Beaux-Arts... while Eiffel's tower was, first and foremost, an engineering project.

Its construction was dictated by mathematics and the need to produce a wind-resistant structure.

And it would be built from material that had never been used for a prestigious building.

-The controversy about the Eiffel Tower at the time was not that it was made of iron.

There was plenty of iron around.

It was that the iron was shown off as a decoration for the city, that the iron was the aesthetic of the building.

-The idea was that metal was good for useful things, such as interior structures in churches, but also passageways -- in banks, in halls, in railway stations, et cetera -- but that we didn't need to show it, unless it was really necessary.

-And the Eiffel Tower announces iron, in a certain sense, has the right to be monumentally present in the city.

-Parisian architecture drew heavily on the past for inspiration, and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts promoted traditional styles.

Haussmannian buildings are a blend of Baroque, Classical, and Renaissance styles.

The Sacré-Coeur, then under construction, recalled the architecture of Romanesque and Byzantine cathedrals.

Stone was the predominant building material.

Iron had to be hidden, like at the Eglise Saint-Augustin, where only the turret revealed the metal framework... or at railway stations, where stone facades concealed the iron supports.

-Even though metal framing was becoming increasingly technical, there were several idealistic, cultural, and regulatory obstacles... since it wasn't until 1878 that Paris regulations authorized visible metal framing.

♪♪ -Iron was the material of choice for engineers.

With it, they could add decorative elements to projects.

And Eiffel received admiration for his Budapest station, which showed off its metal facade.

-The relationship between architect and engineer in the 19th century is one of the most complex and, I would say also, vexed questions of the development of modern professions, but particularly seen from the side of the architects as a really vexing issue.

Because engineering is making possible all sorts of new approaches to architecture -- transparency, great open spaces, spans that are almost unprecedented.

-Bourdais' lighthouse and Gustave Eiffel's tower embodied this fundamental opposition between engineers and architects.

There's the engineer's construction... and there's the architect's art.

♪♪ -This antagonism between those who defended heritage and those who challenged tradition ran deep.

It provided a portrait of a country in upheaval, where the old and the new were now pitted against each other.

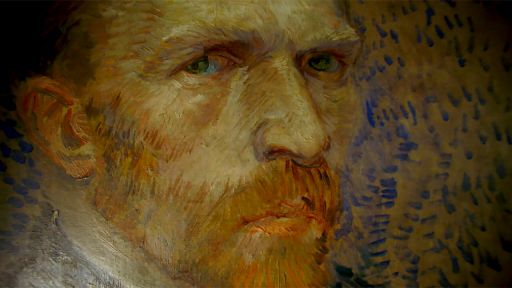

While Bourdais and Eiffel were competing over their tower projects, the first Salon des Indépendants welcomed artists often rejected by official events, like Seurat and his "Bathers at Asnières."

Just a few years earlier, the Impressionists had been trashed by the Academists.

-The arts were all crisscrossed by this fundamental debate between respect for codes and emancipation from them.

In other words, the central question was how to create a new art form.

You had to be of your time.

♪♪ The break with pictorial academicism at the time was colossal, and we can draw a parallel with the Eiffel Tower.

It generated the same kinds of reactions, which were not, in fact, outrageous, but somewhat strong.

-The famous Beaux-Arts painter and teacher Jean Leon Gerome called Impressionist paintings "garbage."

For the supporters of tradition, Gustave Eiffel's tower project was yet another unbearable provocation.

[ Men shouting in French ] -What was essential for the project to move forward was to have the backing of the engineers.

They were the ones who could validate the feasibility of the project.

If the engineers said the project wasn't feasible, it wouldn't go any further.

-He thought it was possible, but he didn't necessarily know yet what difficulties he would encounter.

And that's what was so incredible about those days.

It was the faith in progress and the faith in science.

People threw themselves into challenges because they knew they were going to have difficulties, but they were going to solve them.

-Each man remained confident in his design.

[ Bell ringing ] And there was no indication which one would be chosen for the World's Fair.

But then fate stepped in.

In 1886, Charles de Freycinet, who was close to Bourdais, was made prime minister.

This development prompted Gustave Eiffel to request a meeting with the man in charge of the exhibition -- the new Minister of Commerce and Industry, Edouard Lockroy.

Lockroy was no ordinary politician.

He had fought on the ground during the Paris Commune, served time in prison, and was a committed and popular member of parliament.

The conservative Freycinet brought him into his government as a left-wing ally, but the two didn't get along.

-Lockroy didn't like Freycinet, didn't like this grand bourgeois side of him.

He didn't take kindly to the fact that Freycinet considered Bourdais' tower to be already validated... without even a critical examination.

So he had a hard time of it.

And so Lockroy, perhaps to keep things a little personal and confidential, received Eiffel not at the Ministry, but at his home.

[ Knock on door ] -Lockroy was familiar with Eiffel's work, including the world's highest bridge, and was impressed when the engineer vowed to do even better with his 1,000-foot tower.

-Lockroy was someone whose life had taught him that, in the end, you have to be pragmatic.

-But the politician also knew that Eiffel faced a formidable competitor who already had strong support.

-And for him, the first question was, "Does the man in front of me really have the ability to achieve this goal?"

-He reminded Eiffel that his proposed iron tower had the entire city in an uproar.

Lockroy respected the engineer's point of view but was concerned about the practicalities.

Eiffel insisted that he had always met his deadlines and that his iron tower would be ready for the World's Fair inauguration.

But Lockroy was also worried about the soaring costs of the Fair.

He pointed out that the iron tower would not house any pavilions or provide urban lighting.

Then Eiffel proposed a unique partnership.

He would cover all of the tower's costs in exchange for the revenue from its ticket sales for its first 10 years.

-Lockroy soon realized that Bourdais' project wasn't bad, but it was still very uncertain.

There were risks.

Not only could it fall apart, but it might also simply not be completed on time.

And Eiffel's project was the project of an engineer with a company, with employees, who had built great bridges, great structures.

He claimed to be able to build it.

He also claimed to be able to finance it.

Incidentally, it was not bad, and it wouldn't cost the local authorities or the state very much.

-Eiffel had calculated the revenue admissions to the tower would bring in.

He believed that his investment would be fully repaid within a decade.

-Eiffel must have said, "Well, my project, I believe in it, I support it, and I'm defending it.

If, in addition, I can say that I'm financing it, we'll remove an obstacle.

We'll clear the way to say, look, now I'm bringing you the turnkey project," as it were.

♪♪ -Bourdais' supporters in Paris were worried.

Lockroy had not made his final decision yet, but he seemed to favor the iron tower.

The traditionalists demanded an open competition be held.

So Lockroy drew up the rules.

This document in France's National Archives details one important requirement for a building design to be considered.

-So, in this box, there was a file devoted to the 1889 preparatory competition for the World's Fair, with an extract from the Journal Officiel.

And when you read article nine in particular, it said, "Competitors will be asked to study the possibility of erecting an iron tower on the Champ de Mars, with a 125-square-meter base and 300 meters high."

-So the competition was completely biased, since the definition given was exactly the same as the Eiffel Tower, with the same dimensions, the same technical characteristics, and so on.

-Everything was done to ensure that Eiffel would win the competition and that the competitors would find themselves stuck in the case of a tight competition.

♪♪ -Bourdais realized he'd been tricked.

His Colonne-Soleil, or sun tower, would not qualify for the competition.

He quickly designed a new iron-framed version.

But competitors only had two weeks until they had to present their projects.

-Unlike the other competitors, Eiffel had the time not only to propose a design, but also to propose the beginnings of a technical solution.

Because it's not just a matter of drawing a 300-meter tower.

It's also a matter of explaining what it's going to be made of, how long it will take to build, and how it will stand up.

-This biased competition provoked an outcry in the press, but 107 projects were still submitted.

Short on time, competitors copied the Eiffel Tower with varying degrees of imagination.

Here, a glass roof was added, and there, a bridge straddling the Seine.

On May 28th, the jury reached the unsurprising conclusion that the Eiffel Tower was the only project to meet the competition's requirements fully.

The engineer now had free rein to build what would become the world's tallest tower.

But the exhibition would open in less than three years, and new problems continued to mount.

Against Eiffel's advice, the tower, which was intended to be in the center of the Champ de Mars, was moved to the banks of the Seine to serve as the gateway to the exhibition.

♪♪ ♪♪ The ground near the Seine was waterlogged, making the structural requirements for the tower's foundation much more complicated.

Manufacturers had underestimated the difficulty of building elevators that moved up an inclined plane, and cost estimates soared.

Two residents of the Champ de Mars took the project to court to prevent the tower from being built.

And by the end of 1886, the agreement between the state and the engineer had still not been signed.

♪♪ Six precious months had been lost.

-[ Speaking French ] -Eiffel's opponents may have wondered if tradition might still prevail.

The most illustrious representatives of the Beaux-Arts met in a Parisian salon for their alumni banquet.

Charles Garnier, the architect of the famous Paris Opera House, mocked Eiffel's proposed creation.

The tower was on everyone's mind and the subject of every conversation.

Some believed that the tide could still turn.

Construction hadn't even started yet, and less than two years remained until the opening of the fair.

-[ Speaking French ] -"Mr. Minister, the difficulties beyond my control that have so far prevented the signing of a contract have already put me several months behind schedule.

If I were not in a position to start the work in the first days of January, for which I am absolutely ready, it would be quite impossible for me to complete it on time."

-After three years of constant challenges, Gustave Eiffel had spent a lot of money and energy.

His gamble had become very risky, and the clock was ticking.

-"Therefore, if by December 31st we are unable to reach an agreement, I will regretfully be obliged to relieve myself of my responsibility and withdraw my proposals, renouncing the construction of my building for the Exhibition, which everyone agreed would be one of its main attractions."

-What broke the deadlock was Lockroy's direct intervention to say, "We can't afford to miss the World's Fair.

We decided that the emblem of the Universal Exhibition would be Monsieur Eiffel's tower.

Now we have to go all the way.

We have to sign the Convention."

-On January 8, 1887, the French government finally signed the agreement.

Eiffel obtained a license for the planned 20-year lifetime of the tower to recoup his costs.

But if he didn't complete the tower on time, the state would take control and Eiffel would lose his investment.

Less than two and a half years remained to build the world's tallest building.

♪♪ On January 26th, opposite the Trocadéro and Jules Bourdais' palace, construction of the Eiffel Tower began on the Champ de Mars.

/ Charles Garnier, who had mocked Eiffel's project, was appointed consulting architect of the fair.

But the tower would be built.

♪♪ [ Tools scraping ] Just as construction on the tower got under way, though, Eiffel had to deal with yet another bombshell.

-"We have come, writers, painters, sculptors, architects, passionate lovers of the hitherto untouched beauty of Paris, to protest with all our might, with all our indignation."

-On February 14, 1887, readers of Le Temps discovered a long and virulent "Artists' Protest" in their daily newspaper.

-"A gigantic, black factory chimney, crushing Notre-Dame, the Sainte-Chapelle, the Tour Saint-Jacques, the Louvre, the Invalides dome, the Arc de Triomphe, with its barbaric mass.

All our monuments humiliated.

The tower that commercial America itself wouldn't want.

It is, without doubt, the disgrace of Paris."

-Among the signatories were Beaux-Arts luminaries like composer Charles Gounod and painter Jean Leon Gerome, who had both attended the alumni banquet.

They were joined by writers and poets like Alexandre Dumas Fils, Francois Coppée, Sully Prudhomme, and Guy de Maupassant.

But one name stood out -- Charles Garnier, the fair's consulting architect.

This was the first time he'd publicly attacked the iron tower.

-He was one of the main instigators of the whole thing.

Garnier was so recognized by his peers, he was one of the leaders.

He was forced to take center stage.

It was hard to understand why he shouldn't be the one to do it.

♪♪ -With signatures like these, the protest could have been devastating.

But the complaining artists made a strategic error.

They published their protest in Le Temps, the leading newspaper of the day.

Le Temps was run by prominent newspaper owner and senator Adrien Hébrard.

-Adrien Hébrard, well, he was a close friend of Eiffel, a very close friend.

And Adrien Hébrard warned Eiffel that he had received this protest from the artists.

-Eiffel immediately prepared his response, which was published on the same day, in the same paper.

-"Because we're engineers, does that mean that beauty doesn't preoccupy us?

And while we're making solid, durable products, are we not striving to make them elegant?"

-The effect the artists hoped for was broken by the confrontation of two choices.

One choice was an aesthetic one that Eiffel could denounce as outdated and completely outmoded, faced with the choice of modernity, progress, and a new aesthetic.

-"Among the signatories are men I admire and esteem.

There are others who are known for painting pretty little women putting flowers on their bodices or for having wittily turned a few vaudeville verses.

Well, frankly, I don't think this is all of France."

-The protesting artists were ridiculed.

♪♪ -"Dear Mr. Eiffel, I read in tonight's Temps that you're surprised to see my signature on this petition.

I'm not surprised to see it there, since I put it there.

But what surprises me is it's now completely unnecessary."

-Garnier's signature was on the petition.

How would he explain his public condemnation of the tower?

-"When I signed it, it was before the official treaty was concluded, but once the thing was decided, I declared everywhere that since your tower was to rise, from then on it had to be as good as possible."

-So it's a pirouette, a way of saying, "I'm keeping my ideas to myself, but, naturally, I'm not going to stop you."

-Now Eiffel could devote himself to the project.

The technical challenge was immense, and the engineer had to prove that France was indeed at the forefront of progress.

♪♪ How to build a solid foundation was the first problem to solve.

How could the two pylons be erected near the Seine in waterlogged soil?

The engineer remembered a technique he used at the start of his career in Bordeaux -- using pressurized caissons.

♪♪ ♪♪ Compressed air was injected into the caissons.

This flushed the water out of the ground, which consequently allowed workers to dig with dry feet, until they reached bedrock, 45 feet below ground.

The caisson was then filled with cement and stone to secure the foundations -- a complete success.

On July 1, 1887, the tower began to rise.

Perhaps surprisingly, there were very few workers at the site near the banks of the Seine.

The tower was built in sections in Eiffel's workshops, a few miles from the Champ de Mars.

[ Clanging ] -The Eiffel Tower was built on the principle of assembling elementary parts, which were either flat sheet metal or angle iron, and then doing the final assembly on site.

There were 2,500,000 rivets in all.

Half were installed in the Levallois-Perret plant, the other half on site.

This is really the principle of modern construction -- you could say kit-building today.

Building prefabricated elements, prefabricated in the factory, and simply assembled on site.

♪♪ -The futuristic structure gradually grew taller.

♪♪ The critical step in the monument's construction was joining the four feet that formed its base.

♪♪ -Pylons spaced 100 meters apart, each going in a different direction.

The beams connecting them would have to fit together extremely precisely.

The holes in the parts had to meet exactly.

It wasn't a question of them being offset, otherwise you wouldn't be able to simply drive the rivet in.

So it was very high precision, down to the millimeter, to the tenth of a millimeter.

So we were going to have to find ways of adjusting the angle of inclination of these four large pillars.

-Connecting the base required two processes.

First, hydraulic cylinders lifted the enormous masses of metal just slightly off the ground.

Then, boxes of sand were gradually emptied to tilt the pylons.

These steps ensured the rivets would join the pylons and crossbeams together perfectly.

Less than a year after the first sod was turned, the feet were joined without incident.

♪♪ -The foundations had been laid, the steel structure was in place, and now all that needed to be done was to climb 1,000 feet.

As soon as the second floor was completed, the site was almost certain to be finished.

♪♪ -Construction moved ahead at breakneck speed.

As the tower continued to rise, its critics were left silent.

♪♪ [ Clanging ] ♪♪ On April 1, 1888, the first floor, 190 feet high, was completed.

The second floor, 377 feet up, was finished on August 14th.

A few months later, the tower reached a height of 550 feet, surpassing the Washington Monument.

It was now the world's tallest building.

The construction site attracted throngs of visitors.

No one wanted to miss the progress.

[ Excited conversations ] -People were very interested in it, wondering how it was going to be built, what it would look like on the Champ de Mars.

-One of its signs of the progress of the Eiffel Tower is that you could photograph it once a week and it seemed to be growing like a tree in the tropics.

-Like everyone else, Jules Bourdais watched the tower rise.

He even took a photo of it from the terrace of his Trocadéro palace.

-Bourdais couldn't be on the sidelines.

He had to be in a state of expectation.

"Would this challenge succeed or not?"

He couldn't be indifferent.

[ Cannon fires ] [ Crowd cheering and applauding ] ♪♪ -On March 31, 1889, the Eiffel Tower opened on schedule.

Only the elevators were delayed, forcing Gustave Eiffel and the officials to climb the 1,792 steps to the top.

♪♪ The engineer had met the challenge.

His tower was a triumph for progress and the glory of the French Republic.

[ Fireworks popping ] ♪♪ The World's Fair opened a month later with the world's first 1,000-foot tower.

It was an instant hit with the public.

♪♪ ♪♪ Within six months, almost two million visitors had made the ascent.

Gustave Eiffel recouped his initial investment in full.

The contentious tower had become a national icon.

♪♪ -The Eiffel Tower, once hissed at and scorned, gradually became not only the symbol of Paris, but France as a whole.

In other words, the Eiffel Tower was declared to be a truly French work of art.

It was an expression of French genius.

-The tower's critics had little to say but refused to embrace it.

The fair's consulting architect, Charles Garnier, was present at the inauguration, but he did not climb the tower.

-He was so active.

Once again, he was the leader of the artists' protest.

He was the most prolific in satirizing the Eiffel Tower.

Obviously, he'd put himself out there on this subject and was vulnerable, so he was sulking.

-The indisputable success left Garnier little room for criticism.

The guestbook included some of the biggest names in the world.

The Prince and Princess of Wales... Princess Isabella of Spain... Buffalo Bill... Sarah Bernhardt... and Thomas Edison.

-Very quickly, the tower became internationally renowned.

A lot of articles appeared in the newspapers.

People really marveled at it.

Journalists really got excited about it.

-It was a feat.

It was perceived as a feat.

It could also be the source of a certain bitterness at times, since the English in particular also had very advanced knowledge of metal architecture.

Gustave Eiffel succeeded in doing something that, in all likelihood, English engineers were also capable of doing.

♪♪ -The tower was an astounding triumph for the fair, but its story continued on after the fair closed.

♪♪ ♪♪ Eiffel retired from the company that bore his name and devoted himself to meteorology and aerodynamics.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ But in December 1903, a young army officer, Captain Gustave Ferrié, paid the engineer a visit.

Convinced that wireless telegraphy represented the future, Ferrié spent considerable time researching it.

-Gustave Ferrié was an engineering officer with a polytechnic degree who understood that radio could be an extremely important tool for the army.

Captain Ferrié quickly realized that the tower rising 300 meters above the roofs of Paris would enable long-distance communication.

The challenge was to communicate with forts in Eastern France.

The Vosges Line marked the border with Germany, so there was a strategic need for long-distance communication.

-Eiffel was intrigued.

As a patriot, he offered to pay the cost of moving troops into the tower.

♪♪ His alliance with Captain Ferrié proved vital.

♪♪ In just a few months, the captain's small team began to see success, and by 1906, they could communicate with the eastern frontier.

This was a huge step forward for the army.

The Eiffel Tower was now critically strategic, and there would never be any doubt about the structure's permanence.

Jules Bourdais' palace on the Trocadéro was demolished in 1935 for another World's Fair and replaced by the Palais de Chaillot.

♪♪ When Gustave Eiffel died on December 27, 1923, his tower had been the world's tallest building for 34 years.

But just seven years after Eiffel's death, the "Iron Lady" was dethroned by the 1,046-foot-tall Chrysler Building.

[ Siren wailing ] ♪♪ A year later, the Empire State Building went even further -- 1,250 feet.

With its iron framework, the Eiffel Tower paved the way for modern skyscrapers.

The need to reach for the heavens is now a global phenomenon, extending to Asia and the Middle East.

In 2009, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai became the world's tallest tower at 2,716 feet.

More than 30 towers worldwide have now surpassed the Eiffel Tower... but the Iron Lady will always be the first to have reached the mythical height of 1,000 feet.