Siân Rees, author of The Floating Brothel: The Extraordinary True Story Of An Eighteenth-Century Ship And Its Cargo Of Female Convicts

Ten years ago, while waiting for the bureaucratic wheels to turn in order to get an Australian residence permit, Siân Rees, author of The Floating Brothel: The Extraordinary True Story Of An Eighteenth-Century Ship And Its Cargo Of Female Convicts, spent months in the British Library reading about Australian history. Her general focus was on the early European history of Australia. “I decided not to go,” Rees explains, “but at that time I was fascinated by Australia as well as all things Australian.” Her reading led her to a tantalizing mention of a female-only convict cargo. “It just caught my imagination,” she says. “The idea of this enclosed world of 230 women and a few chaps bouncing around across the ocean for a year. And so having this weird picture in my mind, I was stimulated to go out from there and start research on it.”

Rees’ research began as a hobby with no intention of writing a book. “The great thing about doing that sort of research is that you can digress down any avenue that interests you. It’s not very pretty,” says Rees, “but I did a lot of reading up on women’s sexual health in the eighteenth century and the cures which were being used for syphilis and gonorrhea, as well as the so-called “lock hospitals,” or charitable hospitals, that took in unmarried mothers and prostitutes who had caught venereal disease.” Her search also led her to look for the log of the Lady Juliana — “which [had] been destroyed or at least it is not held in the National Archives.”

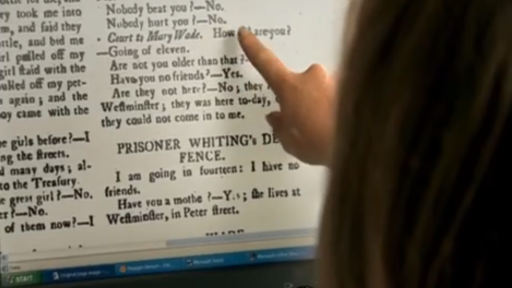

For Rees, the first process is tracking down available documents. “Most of the documents of The Floating Brothel,” says Rees, “were court records of the women who were tried at the Old Bailey, the central court in London in the 1780s. They are now online, but when I was doing the research ten years ago, you had to go to the Guild Hall Library in London and get out enormous books and flip through them until you found the trials that you were interested in.”

Siân Rees and Helen Phillips touring Newgate Prison.

Reviewing the Old Bailey court proceedings uncovered a shocking amount of men and women convicted of highway robbery for stealing no more than the equivalent of 16-pence. Prior to Georgian England, Parliament began to enact a series of strict penal codes, called the “Bloody Codes.” “The 18th-century was a time in which there was an enormous population increase,” explains Rees. “This had a pressure and effect on things like unemployment, hunger, a move of people away from the country towards the cities. In the 1780s, following the end of the American Revolutionary War, there was a perception of a crime wave. There was an enormous demobilized army who was fed up with having fought for King and Country for many years, only to find themselves crippled and in the streets. There was an awful lot of petty crime because there was a lot of destitution. And with this perception of increased crime, came greater severity from the magistrates.”

In the 18th-century, the punishments for crime were either transportation to “parts beyond the seas” or death. The idea of prison as a punishment — penitentiaries — did not catch on until the 19th-century. “So really the magistrates and the judges now seem to be terribly cruel, but they just didn’t have any alternative sentences to hand down.” Rees also explains that “one of the problems that they were up against at that time was that the value that the crimes were assessed — the value that might get you transported or killed if you were a pickpocket — could be as little as six-pence. Which at the time the legislation went through might have been worth something, but in the 1780s in London, it was almost worth nothing. There was no subtlety built into the sentencing system. So whether you stole six-pence or 600 pounds, it counted as the same crime and received the same one-size-fits-all punishment.

Rees found that court records only told part of the story. She needed additional resources to learn about the voyage aboard the Lady Juliana. “The key document,” explains Rees, “was a memoir, a book written by the ship’s steward, John Nicol. Three decades after the event, he wrote a book of his memoirs. One chapter of which is dedicated to the voyage of the Lady Juliana. In fact, while I was doing research, his memoir, which hadn’t been reprinted since 1822, was edited and re-released by an Australian press.”

Siân Rees at the original entrance tunnel to Newgate Prison.

While writing, Rees says, “The most challenging part was the bit that historians are not supposed to do — which is surmising what happens in the gaps. You have documents to tell you what happened, but you have to put in your best guess as to how things join together.” Rees comes from a sailing family. Her father and brother are both boat builders and delivery skippers. “Between them they have sailed practically the whole voyage of the Lady Juliana.” She used their descriptions of currents, wind, temperatures, and bird life to fill in the details of the journey at sea. Rees also called upon her personal experiences with sailing and seasickness to provided details of how it might have been for the women aboard the Lady Juliana.

Rees hopes that the story of the women aboard the Lady Juliana stimulates people to consider “the resilience of ordinary people caught in extraordinary circumstances and that there is no monolithic good and bad, heroes and villains.” She believes that history is much more complicated than “colonials and colonized, oppressed and oppressors, men and women, black and white.” Rees recently began researching a second book on the 19th-century history of the British Royal Navy’s suppression of the Atlantic Slave Trade.