The Andrea Doria steams into New York Harbor amid great fanfare.

The debate about the cause of collision between the Andrea Doria and the Stockholm has been going on since the crash took place in 1956. And even now there are some who disagree with the accepted premise that the Stockholm committed the fatal error that resulted in the collision. What we know for sure is that the Andrea Doria left its home port in Genoa, made several stops, and was nearing New York, its final destination. The Stockholm left New York on its way to Gothenburg, Sweden. The two ships collided about 40 miles southwest of Nantucket and about 110 miles east of Montauk point. At that time there were established sea lanes — meant to keep ships out of each other’s way in this very busy area — but the Stockholm was initially heading north of its prescribed lane in order to help it make good time. Neither ship knew exactly where the other was and at the last minute Carstons ordered his helm to go to the starboard (or the right) and the Doria went to the port (or the left) both thinking that they were opening up the distance between the two ships, when in reality it hastened the collision. There were a lot of mistakes made on both sides that resulted in the terrible accident.

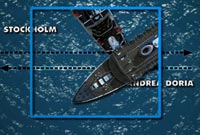

Here is a play-by-play breakdown of some of the most important events that led up to the crash between the Andrea Doira and the Stockholm.

At 9:30 p.m. Captain Piero Calamai ordered a change of course that would take them slightly south of the Nantucket lighthouse.

At 10:00 p.m. A warning indicating there was severe fog in the area was recorded in the Stockholm’s manual, but Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen (the third officer in charge that night) did not act as though he was aware of it.

A graphic of the Stockholm and the Andrea Doria crash.

At 10:30 p.m. Third Officer Carstens-Johannsen changed the Stockholm’s course to a more southern route, in keeping with the ship’s original route. About ten minutes later the Doria spotted the Stockholm on her radar, about seventeen miles away at that point, but clearly directly in the Doria’s way. At this point the Doria expected the other, as yet unidentified ship, would pass the Doria by about a mile to the starboard.

At 11:06 p.m. Carstens-Johannsen detects the Doria on his radar, which he believes is set to a fifteen-mile scale. In fact, the radar was most likely on a five-mile scale. So, while Carstens can see the Doria on his radar, he believes that she is much further away than she actually is. Meanwhile, Doria Captain Calamai decides to swing his ship out to the left to ensure that the gap between the two ships would be even greater than the previous one-mile estimate.

11:08 p.m. Carstens-Johannsen unwittingly brings the Stockholm even closer to the Doria with another course change to the south. At this point Captain Calamai is scanning the fog-riddled sea for a view of the other ship. When Captain Calamai finally gets a glimpse of the Stockholm’s lights he realizes how serious the situation is — the Stockholm is turning directly into the Doria. Calamai panicked, and in a last-bid attempt to save his ship, he ordered a hard left turn hoping to evade the approaching ship. In fact, this turn was a fatal move because it simply exposed the Doria’s side to the bow of the Stockholm.

A little before 11:15 p.m. Carstens-Johannsen realizes what’s happened as the Doria’s lights come into view. He orders full speed astern to help minimize the force of impact and he tries to turn the ship hard to the starboard — away from the Doria.

All these efforts were to no avail. The Stockholm hit and five minutes later the Doria was “listing” (leaning to one side) at more than 20 degrees. The ship was only designed to withstand listing to fifteen degrees, once the tilt became more severe water would flow from one compartment to another and the ship would sink. If the Stockholm had punctured only two of the compartments, the Doria might have been able to stay afloat, but three was too much for her to bear. Another problem was that the extreme angle of the Doria’s listing kept many of the lifeboats on the port side from being launched, complicating the rescue effort substantially. The eight starboard side lifeboats were the only useful ones and they could only hold 1,004 people. There were 1,706 passengers and crew on the Doria, necessitating a massive rescue operation.

The tip of the Andrea Doria as it sank toward the bottom of the ocean.

After the Doria settled at the bottom of the ocean and the world began to speculate about the cause of the crash, Melvin Moscow published a very popular account entitled Collision Course, which held that it was the Doria’s fault the two ships collided. The book was written before much of the forensics were completed on the wreck, but because it was the first to enter the popular consciousness — and because it was well written and exciting — the theory it presented held. A trained naval engineer by the name of John Carrothers furthered the investigation and in 1959 published the first of his findings in an essay. This new information sparked the interest of many on the forensic science side of the marine community and before long Carrothers was working with experts from many of the most important marine institutes in the country. Carrothers and his collaborators determined that once you take into account all the information — all the depositions taken from the various parties involved that day — it seems clear that the only explanation for the crash is that Carstens-Johannsen misread the radar and thought that he had it set on a 15-mile scale when it was actually set to a 5-mile scale.