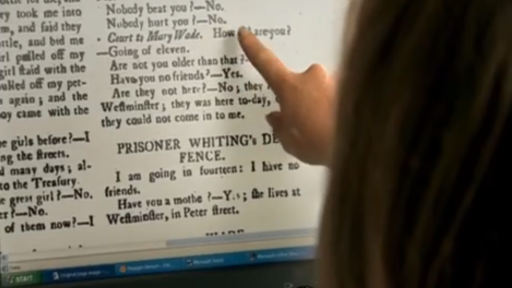

The original Old Bailey court proceedings of Rachel Hoddy’s trial.

At the turn of the 18th century, London, England was both a bustling metropolis and a dark and desperate place. With a population of 800,000 people, London was the largest city in Europe and home to the wealthiest subjects of the British Empire, but it also contained a large population of poor and indigent citizens who sought to eke out a living on the city’s mean streets. In the 1780s, many poor Londoners were confined to the city’s overflowing jails under Georgian England’s “Bloody Code,” which created some 250 capital statutes that were punishable by death or “transportation to lands beyond the seas.” When, under “Mad” King George III, the English crown lost America to the revolutionaries, it lost more than political power and the New World’s valuable resources — it also lost an important dumping ground for English convicts. As its prisons continued to fill beyond capacity, Britain was forced to seek a solution to the problem of its overflowing jails.

In 1788, British Home Secretary Lord Sydney launched the “First Fleet” under the command of Governor Phillip, shipping some 759 convicts and 13 children of convicts along with marines, seamen, merchants and officials as well as sheep, cows, and seed to Australia to create Botany Bay penal colony in present-day Sydney. Upon arrival, Governor Phillip found that Botany Bay lacked both green fields and a water supply. It was also too exposed for ships. So he sailed up the coast into Sydney Harbor and settled at Sydney Cove. The cove had a much bigger natural harbor and its own water supply.

The arrival of the Lady Juliana at Sydney Cove.

The new colony struggled from the start. Diseases like scurvy and dysentery had taken a toll on the settlers even before they had arrived, and food rations quickly began to run low. To make matters worse, the settlers were inexperienced farmers and lacked sufficient labor, so their crops were meager and they lost much of their livestock. Distraught, the colonists turned their anger toward the local aboriginal peoples and, in the summer of 1789, a Botany Bay marine was accused of raping an eight-year-old girl. Reports of such atrocities as well as the colonist’s difficulties soon reached Lord Sydney’s right-hand man, British Home Under-Secretary Evan Nepean. Nepean decided that, in order for the new colony to prosper, it would need more than just increased provisions and supplies — it would need the stability created by more women, children, and families. To this end, Nepean ordered a shipment of female convicts to immediately be sent to Sydney Cove and “upon landing, promote a matrimonial connection to improve morals and secure settlement.”

In response to Nepean’s command, 225 female thieves, prostitutes, con artists, and some five infants were rounded up from prisons in London and the English countryside to be shipped off to the failing Sydney Cove colony aboard the Lady Juliana. For the English government, the female convicts were to serve two purposes: to prevent the starving and isolated male colonists from engaging in “gross irregularities” and to act as a breeding stock for the troubled settlement.

The Lady Juliana left the shores of England the first week in July 1789. Its ten-month journey would take it through the Canary Islands and to Cape Verde, then on to Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town before arriving at Sydney Cove. The women slept in the orlop deck, just above the ship’s bilge, which contained the ship’s holding water, human waste, and remnants of food. Despite such hardships, the ship’s conditions may have seemed preferable to many of the women compared with those they had left behind in London’s prisons. For some of these women, the journey to Sydney Cove itself offered an opportunity for them to better their positions. Women who became “wives” of crewmembers aboard the ship could get access to better provisions and sleeping arrangements. Some women, like Elizabeth Barnsley — a wealthy and successful shoplifter convicted of theft — used their money and influence to procure better lodging and even to create business opportunities on the ship. Prostitution was not unusual in Georgian England or within the shipping industry, and the Lady Juliana soon became something of a “floating brothel.” Crewmembers and, possibly, some of the ship’s female cargo profited from the sex trade in various ports of call, and money earned from prostitution could in turn be used to gain influence on the ship or upon arrival at Sydney Cove.

After ten months at sea, the Lady Juliana arrived at the desperate, starving Sydney Cove colony. They did not receive a warm reception. The colonists had expected food and supplies — not a cargo of over 200 women and as many as seven newborn infants — and they made their disappointment clear to the women of the Lady Juliana. However, the colonists’ ire eased after the supply ships Justinian, Surprize, Neptune, and Scarborough arrived in Sydney Cove just three weeks after the Lady Juliana. For their part, many of the women convicts experienced a newfound sense of freedom at Sydney Cove. Freed from the strictures of traditional society and class, these women saw their new home as a chance to create a new life for themselves — a life filled with unprecedented opportunities.

Ann Marsh managing her company, the Parramatta River Boat Service.

Over 200 years later, three contemporary Australian women set out to unravel the stories of how their ancestors came to be aboard the Lady Juliana: Helen Phillips, a senior Anglican minister for the diocese of Tasmania,is a descendent of a prostitute named Rachel Hoddy; Delia Dray, a sheep farmer and senior government horticulturist, traces her lineage back to Ann Marsh, who was convicted of stealing a bushel of wheat; and Meagen Benson, a successful bank communications manager, is a distant relative of Mary Wade, a destitute 11-year-old street urchin who was sentenced to death for stealing another child’s clothes. Using old court records, newspaper archives, shipping logs, and excerpts from an account of the Lady Juliana’s voyage set down by ship steward John Nicol, the three women find out just how their ancestors came to be imprisoned and transported to Australia, and what became of them once they reached the failing colony.

Ms. Phillips, Ms. Dray, and Ms. Benson ultimately discover that, despite being branded “criminals” and being exiled from their native country, their ancestors and many of the 225 women aboard the Lady Juliana were also the founding mothers of Australia. After becoming the colony’s midwife and serving out the remainder of her sentence, Elizabeth Barnsley is thought to have earned enough money to purchase her passage back to England. In 1823, Rachel Hoddy applied for a license to sell liquor, beer, and wine and became the only woman in Hobart Town to operate a pub, “The Horse and Groom.” Ann Marsh became Australia’s first great female entrepreneur founding the Parramatta River Boat Service, which still runs today. And by the time she died at 87, Mary Wade had become Australia’s greatest matriarch, heading a five generation family with more than 300 members.