It’s likely that researchers will never come to an agreement about where syphilis originated and how it arrived in the Old World. The most widely accepted theory is that the venereal form of the disease arrived on the shores of Europe along with Christopher Columbus’s crew, when they returned in 1493 from a journey to the New World. Indeed, although no cases of the disease seem to have existed in Europe before Columbus sailed to the New World, it had reached epidemic levels on the continent by around 1500. But in recent years, pre-Columbian skeletons — such as those unearthed at the Hull friary in England — have been found with distinctive signs of syphilis. Those skeletons have turned the nice, tidy picture of New World origins into a muddy mess.

It’s likely that researchers will never come to an agreement about where syphilis originated and how it arrived in the Old World. The most widely accepted theory is that the venereal form of the disease arrived on the shores of Europe along with Christopher Columbus’s crew, when they returned in 1493 from a journey to the New World. Indeed, although no cases of the disease seem to have existed in Europe before Columbus sailed to the New World, it had reached epidemic levels on the continent by around 1500. But in recent years, pre-Columbian skeletons — such as those unearthed at the Hull friary in England — have been found with distinctive signs of syphilis. Those skeletons have turned the nice, tidy picture of New World origins into a muddy mess.

The sexually transmitted form of syphilis is caused by a corkscrew-shaped bacterium called Treponema pallidum, which is one of a closely-related group of bacteria called the treponomes. Other treponomes are responsible for the three non-venereal forms of syphilis, which primarily affect the skin and are most common in early childhood. Bejel, also caused by Treponema pallidum, is prevalent among Bedouin tribes and elsewhere in the Middle East; pinta, caused by the Treponema carateum bacterium, is common in Central and South America; and yaws, the result of infection with the Treponema pertenue bacterium, is found in moist, tropical regions throughout the world. Venereal syphilis probably mutated out of one of those other forms — most likely, researchers say, from the bacterium that causes yaws. When that happened, however, is the big mystery.

Researchers do know, however, that the syphilis bacterium has been causing disease for thousands of years. Back in 1987, rheumatologist Bruce Rothschild of the Northeastern Universities College of Medicine in Youngstown, Ohio, and William Turbill of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, reported that they’d detected the chemical signature of syphilis in the bones of an 11,000-year-old bear. The bones of the bear, which once lived in what is now Indiana, showed damage similar to that seen in humans with the disease, and tested positive for antibodies to the syphilis bacterium. The earliest signs of syphilis in humans date back to about 2,000 years ago, in remains found on the Colorado Plateau of North America. More recently, Rothschild found skeletal evidence for syphilis in remains from the Dominican Republic dating back between 1,200 and 500 years ago, in an area known to have been visited by Columbus and his crew. That evidence, he says, indicates that the disease could easily have spread from New World to Old by Columbus’s crew.

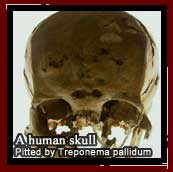

But other researchers say that there is simply too much evidence of pre-Columbian syphilis in the Old World to ignore. Archaeologists have found ancient skeletons with tell-tale signs of syphilis, such as thickening in the lower leg bones and pitting in the skull, at half a dozen sites in England, and also in Italy, Israel, and other locations in Europe. The clear implication is that the venereal form of syphilis was already present in Europe before Columbus’s voyage. “There is a suggestion that it might have originally come from Southeast Asia and then maybe spread both east and west,” says biological anthropologist Charlotte Roberts of the University of Durham in England. “But who knows? There are many places throughout the world that have not been examined for skeletal evidence of syphilis — China, India, Russia — so I think it’s really dangerous to start hypothesizing about where it is coming from and at what time, until we have more data. Maybe in ten years we’ll have a better idea.”