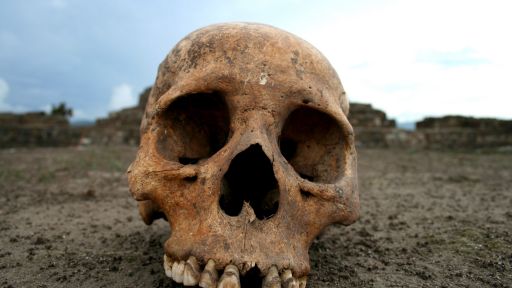

Archaeologists make a grisly find: Four hundred skeletons buried in a mass grave. The bodies have lain undisturbed for 500 years, since the time of the Spanish conquest. But this is no ordinary grave site. The remains suggest these people met a gruesome end at the hands of the Aztecs, who ruled Mesoamerica in the 14th through 16th centuries. But who were the victims and why were they killed?

The forensic experts first expected to find that all the bodies were indigenous — belonging to members of local tribes who had been captured by the Aztecs. The skulls of these indigenous people would normally have a broad forehead and wide cheekbones. But intriguingly, some of the skulls from Zultepec didn’t fit that profile. Of the 400 skeletons found so far, as many as 40 seem to be from Europe. The discovery is completely unexpected, and immediately raises questions about how the bodies got there.

With a population of more than 28 million, Mexico City is the largest metropolis in the western hemisphere — the second biggest city in the entire world. It’s a vibrant and chaotic mix of movement and color. But these teeming streets once had a very different look. Five centuries ago, this was the center of the Aztec world, the capital city of Tenochtitlan.

Archaeologists Elizabeth Baquedano and Enrique Martinez

A wandering tribe of Aztecs from the north settled on this swampy part of central Mexico in the 1300’s. From migratory beginnings, they rose up to rule an Empire for three hundred years. The Aztecs were fierce warriors, who ruthlessly conquered and subjugated neighboring peoples to become the dominant force in the region. Their power and ferocity is well documented, but the scope of the killings at Zultepec has shocked even the most knowledgeable Aztec experts.

Records show that sacrifice was central to Aztec culture. The Aztec concept of the world, their understanding of the universe, and their right to live and participate in it was based in the act of sacrifice to the gods. To them, sacrifice was not a form of punishment, but the ultimate opportunity to do one’s part for the perpetuation of the universe. Human sacrifice was required to keep their world turning. The Aztecs practiced the ritual with great frequency, using their enemies as the sacrificial lambs.

In 1519, the wily and determined conquistador Hernán Cortés was peacefully received by Emperor Montezuma, a sophisticated leader born of Aztec royalty, in Tenochtitlan. Montezuma had been warned of the Spaniard’s arrival, and was unsettled by this white-skinned man riding a strange, unknown beast. He thought Cortés’ appearance might be the fulfillment of an ancient prophesy about a returning Aztec god, Quetzalcoatl who was said to have disappeared over the seas in the East and would be returning. Though wary, Montezuma made a great effort to play the perfect host, showing his guests around the city and entertaining them with lavish banquets. But despite the regal treatment, Cortés remained suspicious — sure that the Aztec leader was planning something sinister. Cortés made the decision to act first and took Montezuma captive. But soon after, a second party of Spaniards followed Cortés to Mexico. They were sent to arrest him, since he had left on his mission without Spanish consent.

Leaving a small garrison in charge of the Aztec capital, Cortés marched east with a band of his finest soldiers. He arrived back at the coast and went to battle — quickly vanquishing his would-be captors. Not wanting to stay away from Tenochtitlan any longer than necessary, Cortés immediately gathered up the defeated soldiers and their entourage of women and slaves, and set off on his return trip. With few horses and an ever-growing number of men and women in tow, the column’s progress slowed to a crawl. Cortés made the crucial decision to leave the slow masses behind and move ahead faster with just a small group of soldiers. He never mentioned the convoy again.

The large group, abandoned by Cortés and still moving slowly, had little choice but to continue making its way west towards the capital. Despite their numbers, they had few weapons and even fewer trained soldiers. They must have seemed like an easy target for the well-trained Aztec warriors. There are no records about the final attack, but it was only a matter of time before the convoy was overrun.

The Aztecs had an intimate knowledge of the area, the element of surprise, and a prowess for ambushing in the dark. As was their custom, the Aztecs would have captured their enemies alive. Their fates would be sealed on the altar, not the battlefield. In Zultapec, the Spanish would become the latest offering to the Aztec gods.

The widely accepted view, is that the Conquistadors took on the mighty Aztec nation, and brought down their Empire with little resistance. But this history, of course, has been written by the victors. The bodies at Zultapec lay bare the myth that the Spaniards just simply moved in and the Aztecs rolled over and just gave up. In reality they didn’t; they fought hard.