UPDATE

As sometimes happens when working with the scientific community, and new technologies are developed, further research reveals that previous findings were incorrect. This is what happened with the Secrets of the Dead episode Titanic’s Ghost.

Additional research performed by the American Armed Forces Identification Laboratory and bio-anthropologist Dr. Ryan Parr, who conducted the initial tests, determined that the remains of the unknown child were those of Sidney Leslie Goodwin and not Eino Panula, as the program concluded.

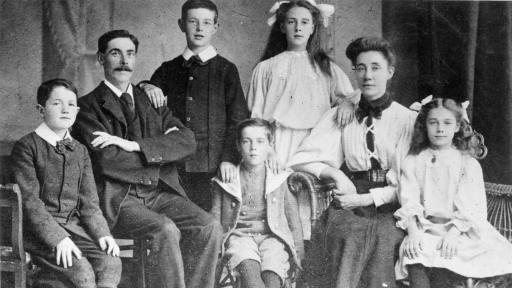

Joan Allison’s grandmother, Catherine Wallis.

Below are comments from Dr. Parr from interview he gave in 2009 with the producers of Titanic’s Ghost in which explains how and why his conclusion about the identity of the unknown child changed.

The first place we looked for the identity of the unknown child was Gosta Leonard Paulson.

And we were able to rule that possibility out by comparing the DNA signature to a maternal relative.

When we got to Eino Panula, there was a match. Or at least, we couldn’t disallow Eino Panula from the matching process. However, there was a child who was several months older, ninteen months older, that was Sidney Leslie Goodwin, that matched as well.

There was a genetic match between the Panula child, the Goodwin child and the DNA sequence from the unknown child. However you have this other line of evidence…

Some dental experts and some archaeological experts had been looking at the teeth. The three small teeth that had been recovered. Now asking someone to date someone or to age them using three small teeth that had been in the ground for close to ninety years, it’s a pretty big job. But nevertheless, the estimates went all the way from under six months to thirty-six months. Um, two of the investigators that had looked extensively at teeth in archaeological settings had sort of put this limit between six months and fifteen months.

Panula fit within that age range

So in that case of, we had this genetic tie, we broke the tie using the dental evidence,

…and went with the younger child, which seemed appropriate at that particular time.

But nevertheless, I think there was just a general sort of unease in the back of your mind. You always ask yourself, “Have I done everything I could do?” Was the effort good enough? Even though the evidence said that this was indeed Eino Panula, you know, you’re always second-guessing yourself. And at that time, oddly enough, there was the appearance of what I like to refer to as the Northover shoes. Where, um a family in Ontario had brought forth these small pair of shoes that was purportedly associated with the unknown child.

And if you look at the description of this small child that was written by the men on the Mackay-Bennett,

…that description records a pair of brown shoes, which is very consistent with the brown shoes that were donated by the Northover family.

If you look at the shoes, there are indications that this child is older. The Bata Shoes museum out of Toronto analyzed them and stated that these are the shoes of a two-year-old.

And those shoes… …were determined by the Maritime Museum to probably be authentic.

So now, you introduce this possibility that, wow, maybe you aren’t right, you ought to do more.

So really, what you’re trying to do, is you’re trying to match or disassociate three different individuals. The unknown child, the Goodwin child and the Panula child. And when we actually looked further in the DNA characterization,

…we found that there was one subtle difference in our second expanded analyses. And that subtly difference indicated that it was more likely the older child or the Goodwin child, as opposed to the Panula child.

But it was a very small difference. It was only one difference, which isn’t a lot.

At this point, we were fortunate enough to begin a collaboration with the American Armed Forces Identification Laboratory. And they told me that there actually has to be two differences for them to be able to conclude that there actually was a difference between the Goodwin and the Panula family pedigrees. So they took on the project and it was really quite difficult because these pedigrees were really quite close. But they persisted and worked very hard and were able to find one more difference that was consistent with the Goodwin family as opposed to the Panula child.

Now, we found two difference and there is a lot of relief. Because I think all of the obscurity, the nagging, the lingering doubts have just been washed away. So I think that we finally reached a conclusion. And a consensus that this was not Eino Panula, but was actually Sidney Leslie Goodwin.

Sydney’s father, Fredrick Goodwin was the patriarch of the family and he had a brother that was working at the Niagara Falls power plant. And he sent a message over to his brother, to Fredrick, saying, “Hey, you know what? I think there’s probably a job for you in America here, in the new land.” And so Fredrick brought his family over, or intended to. Interestingly enough, they were poor, like most of the, the um, passage trade. And they were booked to sail on a much smaller steamer. But because of the coal strike, they were upgraded to the Titanic.

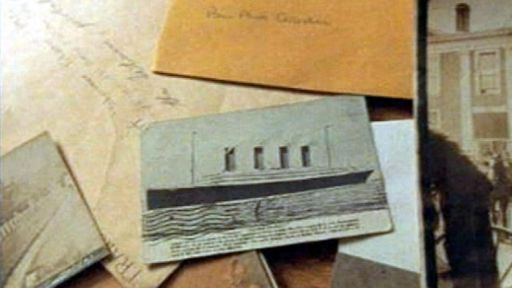

On April 10, 1912, the largest, most elegant luxury liner in the world set sail from Southampton, England. At 46,000 tons, the Titanic was, at the time, the largest moving object ever built.

On the evening of Sunday, April 14, 1912, three passengers on board the Titanic were anticipating their arrival in America. Catherine Wallis was a 35-year-old widow with four children at home in Southampton, England. As a third-class matron, she tended to the needs of the third-class passengers. Two-year-old Gosta Paulson and his three siblings were traveling from Sweden with their mother, Alma, to meet their father, Nils, in Chicago. Two years earlier, Nils was forced to leave the country in the wake of a coal mining strike. He had since been working as a trolley operator and saving enough money to move his family to the United States. Although born and raised in rural England, Charlie Shorney’s work as the valet for a wealthy family had enabled him to travel. His worldliness spawned an ambitious plan; with half the family silver in tow, Shorney was on his way to meet his fiancée Marguerite and start one of the first taxi cab companies in New York City. Inspired by the notion of sailing on the world’s greatest vessel, Shorney had changed his ticket so that he could ride on the Titanic. It was a fatal decision. Titanic was headed directly into an ice field 80 miles long.

Fairview Lawn Cemetery

At 11:40 p.m., April 14, lookouts spotted an iceberg in the ship’s path, but it was too late. Titanic hit the iceberg and water began to flood into the forward hull. The ship was totally submerged by 2:20 a.m. Catherine, Gosta, and Charlie never made it to America.

More than 1,500 passengers perished when Titanic sank. Two days later, a Canadian salvage ship, the Mackay-Bennett, left port in Halifax, Nova Scotia, sailing 700 nautical miles southeast to the scene of the ocean liner disaster. All in all, the sailors were able to recover over 300 bodies from the water. The sailors numbered each of the bodies, buried some at sea, and brought the rest back to Halifax. Many of the unidentified vctims were buried in graves in Halifax’s Fairview Lawn cemetery.

Among the unidentified victims recovered by the shipmates of the Mackay-Bennett was a young blond boy described in the coroner’s report as being around two years of age. The sailors were so moved by the fate of this unknown child that they arranged a funeral service for the boy and had a headstone placed on his grave, which they dedicated “to the memory of an unknown child.” The little boy’s grave has come to symbolize all the children who perished on the Titanic.

Ninety years later, Catherine Wallis’ granddaughter, Joan Allison, is trying to put her grandmother to rest. Hopeful that her grandmother might have been buried in one of these graves, Allison contacted historian Alan Ruffman. Searching through coroner’s reports in the Public Archives of Nova Scotia, Ruffman identified a victim that fit the description of Catherine Wallis and, with the help of DNA expert Dr. Ryan Parr of Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario, sought to solve Joan Allison’s mystery. Inspired by their task, Ruffman and Parr continued working to identify victims of the Titanic. With a little luck, they hoped to pinpoint the resting-places of Gosta Paulson and Charlie Shorney.