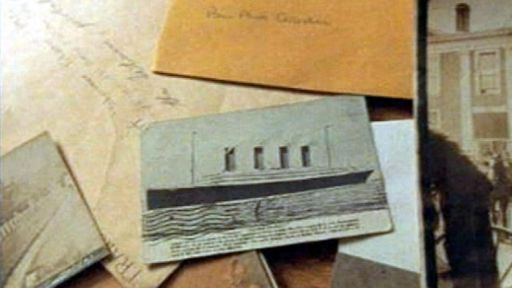

In a way, identifying the remains of Titanic victims has been a decades-long process that began when the ship sank in 1912. Although there was no genetic technology available to identify bodies distorted by six days afloat at sea, the investigators of the day had methods that are still useful to the scientists continuing this work today.

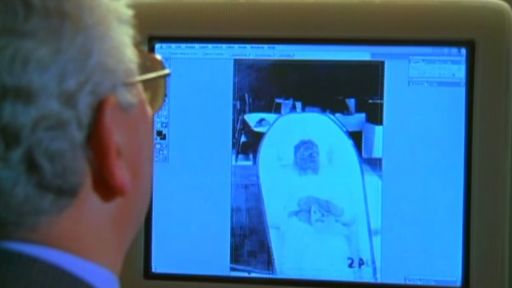

Dr. Ryan Parr

There were, of course, limitations to such rudimentary investigatory techniques. Parr suspects many of the unidentified victims were crewmen who had been working in the bowels of the ship. “You probably worked in light clothing, and your papers were in your cabin. If you made it topside before the ship went down, you certainly didn’t worry about your personal belongings. Also, communications weren’t very fast at the time. My guess is that the authorities wouldn’t have known who to contact. They had a passenger list, but I’m not sure that anyone put down the names of emergency contacts. Today, we always do that, but not back then. And to actually make an identification you would have to make a physical identification, someone would have to look at the body and claim it. These were poor immigrants and their families probably weren’t even made aware of the disaster in a timely, official fashion, hence, bodies were buried before relatives heard about it or could even arrange to come to Halifax.”

Thanks to historian Alan Ruffman’s work recovering the original coroners’ reports from the Public Archives of Nova Scotia, Parr has been able to apply his expertise in modern DNA analysis to continue the work of Titanic’s first investigators. Naturally, there are still limitations to what he can do. “The problem with DNA analysis is that, like any venerable artifact, DNA falls apart over time, and so it must be reconstructed,” he says. “When DNA degrades, it usually just leaves you with short, small pieces.”

Once mitochondrial DNA has been obtained from a maternal relative and the remains of the Titanic victims themselves, Parr puts these pieces together. “If a living maternal relative is willing to participate, the ‘family names’ inscribed in the DNA can be compared. In this way family identifications can be made. In a sense, it’s like interviewing the dead … asking them who they are. In the case of ‘an unknown child,’ there were some modest remains left from which to attempt DNA recovery. This material is treated chemically to extract DNA, while trying to eliminate everything that isn’t DNA. Hopefully you are left with DNA that is intact enough to ‘copy’ and compare to a maternal relative.”

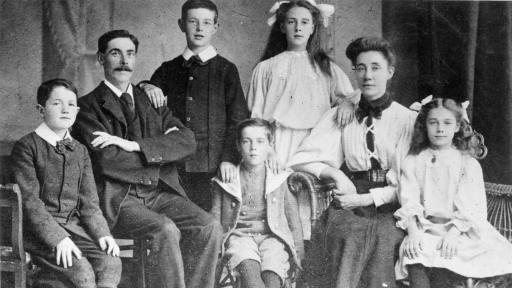

Although Parr concedes that, “the chances of your lost relative being one of the unknowns are very, very slim,” that reality hasn’t prevented families from participating in the DNA testing. “It happened 90 years ago, but to many people with relatives who actually had to deal with the loss of a loved one, it’s still with them. The sense of family with these people is very strong. For example, there was a man in Halifax who chained himself to the grave marker of the unknown child and said, ‘I’m not going to let them do this exhumation, because I’ve appointed myself caretaker of this child.’ And I called the relatives in Sweden and I told them there might be a lot of controversy surrounding the exhumation and I asked them whether they were sure they wanted to go ahead with things. And one of them said he was incensed that someone would claim this spot of land, which potentially held the remains of his relative. And he said he was sure he wanted to continue with the identification process, because if this unknown child was his relative, he deserved a name. There are a lot of people who have a romantic fascination with the Titanic, but the victims were real people, and when the ship went down, there were a lot of individuals and families left to deal with the tragedy. There is never anything romantic about that aspect of it.”