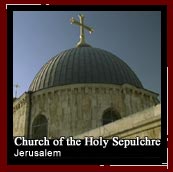

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, located in the northwest quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, was built originally by Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor of Rome. The church, dedicated in 336 A.D., was said to enclose both the site of Christ’s crucifixion (Golgotha), and the rock-cut tomb in which he was said to have been buried. To enclose the tomb, which had previously been covered by a pagan Roman temple, Constantine’s engineers had to cut away the hillside into which it had been carved, leaving a freestanding plug of rock jutting out into the landscape. An edicule, or “little house,” was built over the tomb, to protect and cover it; a gold-domed rotunda, 65 feet in diameter, called the Dome of the Anastasis (Resurrection), covered the edicule, and a great basilica extended eastward from the tomb.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, located in the northwest quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, was built originally by Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor of Rome. The church, dedicated in 336 A.D., was said to enclose both the site of Christ’s crucifixion (Golgotha), and the rock-cut tomb in which he was said to have been buried. To enclose the tomb, which had previously been covered by a pagan Roman temple, Constantine’s engineers had to cut away the hillside into which it had been carved, leaving a freestanding plug of rock jutting out into the landscape. An edicule, or “little house,” was built over the tomb, to protect and cover it; a gold-domed rotunda, 65 feet in diameter, called the Dome of the Anastasis (Resurrection), covered the edicule, and a great basilica extended eastward from the tomb.

Over the centuries, the church was destroyed and restored many times. It was burned by the Persians in 614, and rebuilt by Abbot Modestus in 626, then destroyed again in 1009 by the Egyptian caliph al-Hakim Bi-Amr Allah. A new church and a second edicule were built in the early 11th century. In 1555, the third incarnation of the edicule was constructed. When that structure and much of the rotunda and basilica were badly damaged by a fire in 1808, the fourth, and current, edicule was built. It still stands, although it had to be reinforced with a scaffold of steel girders in 1947 and is badly in need of repair.

That restoration will not take place, however, until the various religious communities that hold rights to the Church can agree on how to proceed. Under an agreement called the Status Quo of the Holy Places, issued in 1852 by the Ottoman Turks (who then controlled Jerusalem), six Christian communities share space within the building. The three smallest sects, with the fewest possessions and the least power, are the Egyptian Coptic Orthodox, the Syrian-Jacobite Orthodox, and — poorest of all the communities — the Ethiopian Orthodox, which has control of two chapels, including one that sits on the roof of another chapel. The three “great” communities, which jointly own the floor of the rotunda (on which the edicule sits) and the tomb itself, are the Greek Orthodox, the Roman Catholics, and the Armenian Orthodox. (As is the case with the smaller communities, each of the three great denominations also individually holds the rights to particular chapels within the church.)

That restoration will not take place, however, until the various religious communities that hold rights to the Church can agree on how to proceed. Under an agreement called the Status Quo of the Holy Places, issued in 1852 by the Ottoman Turks (who then controlled Jerusalem), six Christian communities share space within the building. The three smallest sects, with the fewest possessions and the least power, are the Egyptian Coptic Orthodox, the Syrian-Jacobite Orthodox, and — poorest of all the communities — the Ethiopian Orthodox, which has control of two chapels, including one that sits on the roof of another chapel. The three “great” communities, which jointly own the floor of the rotunda (on which the edicule sits) and the tomb itself, are the Greek Orthodox, the Roman Catholics, and the Armenian Orthodox. (As is the case with the smaller communities, each of the three great denominations also individually holds the rights to particular chapels within the church.)

“There is no one stone in the rotunda floor or the edicule that you can say is Greek or Latin or Armenian. They own that part in common, and so they have to agree on anything that will be done,” says archeologist Martin Biddle of Oxford University, who has spent the past decade surveying the church and the edicule. “The restoration has been a slow process, because they all represent different nationalities, different artistic traditions, different theological traditions, and so forth. But they have managed to agree on the restoration of the whole church except for the tomb and the floor around it, so my guess is that they are going to agree eventually. But it is not going to be a particularly quick process, unless, of course, it falls down, in which case something will have to be done immediately.”